(This post sponsored by our publishing partner Cripple Creek Backcountry.)

Dynafit is proud of their gradated color logos. Said to not be the easiest thing to accomplish on nylon (Grilamid) plastic.

I was recently in Montebelluna, Italy, checking out a full gamut of secret Dynafit boot happenings. Most interesting? Seeing various boots punished on a Fritz Barthel contraption I call the “Butter Churner,” (as a few of the parts came from eponymous machinery).

No photos allowed for now. Fantasy is better anyway. Buxom Tyrolean lass in the midst of a green field full of dairy cows? Not quite. Envision a tower about three feet tall, built with threaded rod, steel plates, and bushings. A worm gear system is attached to a load cell and measurement instrument. Parts of the tower move and load an artificial leg-foot in a boot, which in turn is tightly clamped to a frame.

As the Butter Churner does its thing, you might eventually get a popped rivet in your eye, but not until you’ve taken things way beyond the normal forces of skiing. The main purpose is to compare different model boots, as well as verifying changes in design that result in different flex ratings. “Hey, hold my beer espresso and watch this,” is the kind of thing you might hear as the Butter Churner whirs.

A word about boot testing during the development process. The test boots come to the workshop directly from the injection molding facility, in pieces. Each time the mold is changed they output evaluation parts. A technician hand assembles the boots, one at a time. They’re then tested, on the bench for quantified stiffness and durability, with major iterations skied on-snow for overall performance and feel.

Oh, and about that PDG-2 (a nice lightweight style boot, by the way), how about some factory snapshots?

As with many factories, no reason to tout what goes on inside. This is an assembly plant, injection molding is done elsewhere. A few other brand ski boots are made here as well. The hissing of compressed air driven machinery greets you at the door, accompanied by the smell of grease and plastic. Not unpleasant, the sounds and smells of making.

Zipper cover, attached with special adhesive. Handwork results in precise placement without ugly glue overage.

The now classic logo, etched and ready to ski. I’m told creating this sort of colored engraving on fabric is not easy. Nothing to do with the boot’s performance, but design details do have a role. How much of a role is debatable, but a discrete logo is ok by me.

Cuffs are pressed at a nearby factory, using carbon pre-preg material. The upper buckle and “Ultra-Lock hole is shown, for this to function it’s essential that assembly be accurate. I got curious about how they allocate workers for specific tasks, related to quality. In this case, Dynafit concentrates on individuals performing a limited number of tasks, a perfectly as possible. “In this case, quality control is more important than speed,” according to the production manager. Apparently some factories rotate workers through a variety of work stations, to prevent over-use injuries and boredom. As the ski boot production cycle is not “endless” they can train workers on specific tasks with less concern about such things. The workers appeared to have things down pat.

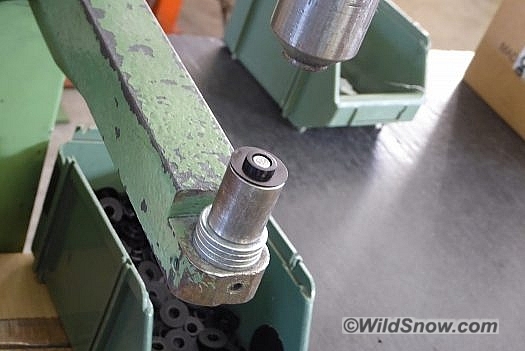

The boot is placed in a press that inserts the Master Step, fastened from the inside with a torque controlled screwdriver.

The line, machine obscured for privacy reasons. Much of the machinery in these factories is custom-made specifically for ski boots. In general, sharing photos is discouraged though most of the gear and operation is industry common.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.