Depending on the terrain, a heel hit with a riser flipped over the pins might offer the most efficient mode for ascent and transitions.

Riser options — the debate rages on. Let’s agree that personal preferences are ok when it comes to riser heights. And to build efficiencies at transitions, sometimes it makes sense to skin with a riser flipped over a tech binding’s pins.

There’s a lot of arcane background skiing knowledge to learn. Some of it comes from years of experience and learning about suspect snow slopes and your ability to make wise decisions. Other aspects of the sport, like gear, shouldn’t be so complex. In this binding primer, we’re focusing solely on tech bindings possessing some racing DNA and efficient use of those heel units.

The passing of the race DNA to some hybrid offspring doesn’t require a Punnett Square. We’ll break it down and keep it simple.

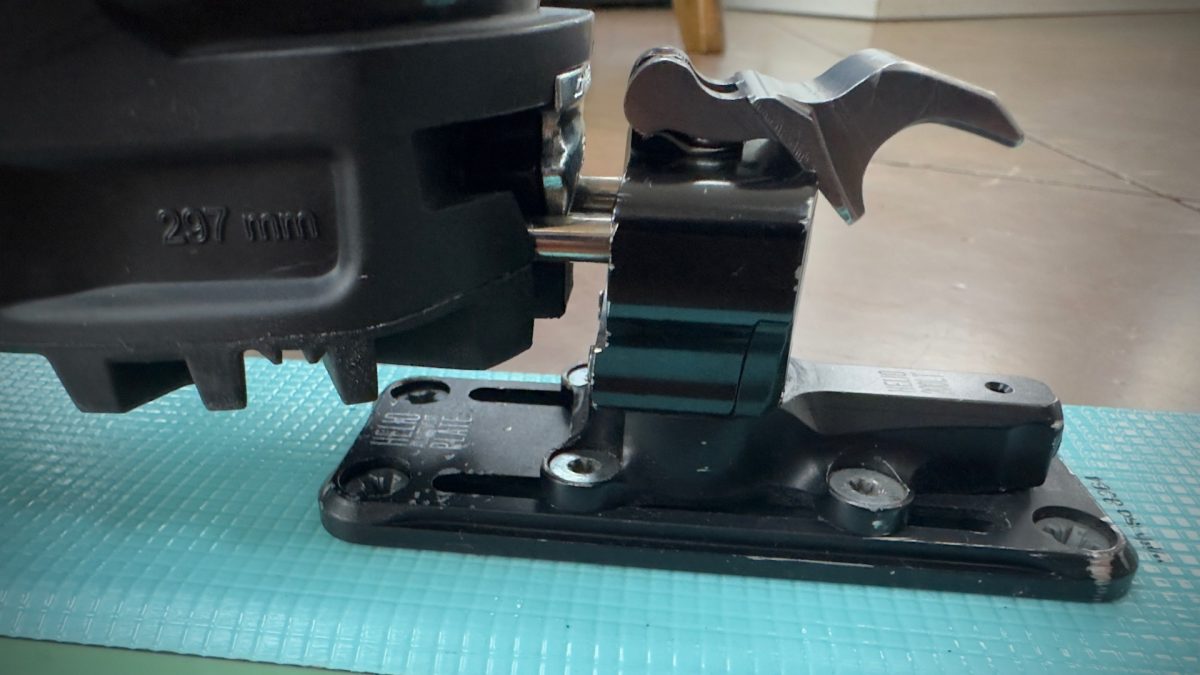

The boot heel, when pushed down, will snap into the pins. Shown here is a Hagan Ultra WC race binding. A model made by ATK that is very similar to their race offerings.

The heel of the Hagan Ultra WC is set in the pins forward position with the lone riser flipped over the pins.

Race bindings are light. Some weigh nearly 100g (toe + heel). We’re interested in tech bindings with a bit of a bump in weight, the 170g to 220g range. The added weight often means a more durable binding. And since we are talking about using this binding way way way off-piste, we want some durability.

Race bindings offer a limited, but oftentimes sufficient, set of riser options. Usually, this means a single riser that flips over the pins providing roughly +25-30mm of added height.

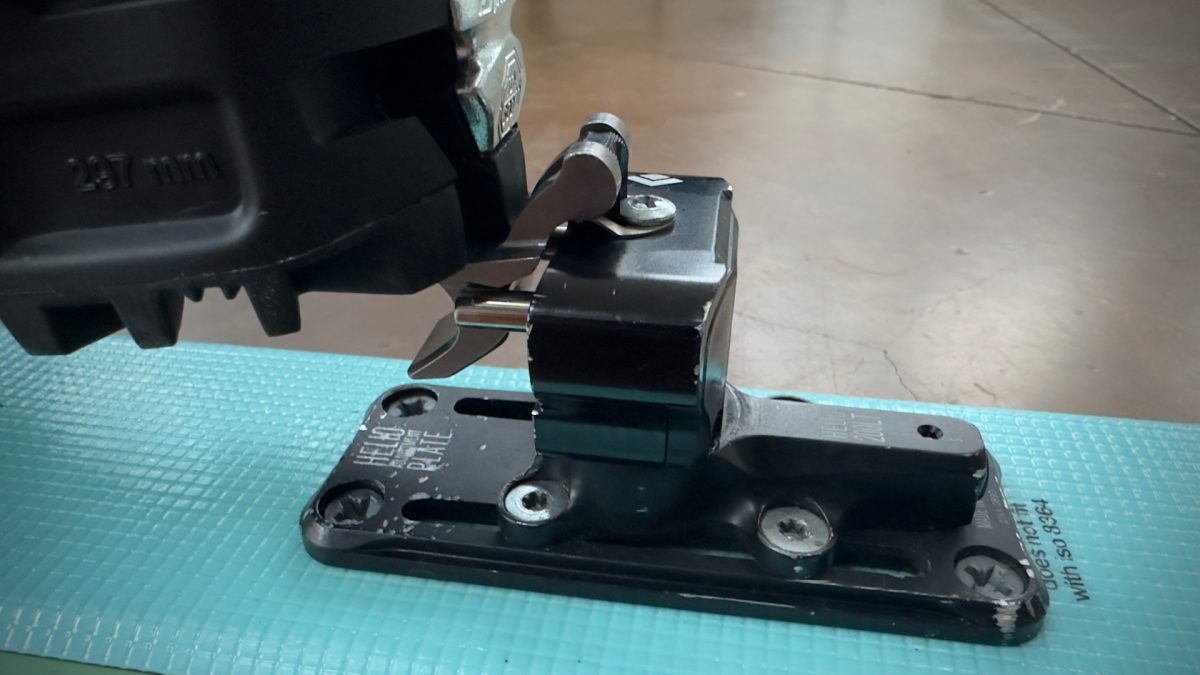

A sky view of the Hagan Ultra WC race binding. In this orientation, the heel is rotated into flat mode.

Several companies market their race bindings as including a flat mode. Engage this mode when the binding is rotated 90 degrees from pins forward. In our experience, these flat modes can be finicky; there’s not a ton of clearance between the boot’s heel and the binding when lowering the heel. For example, the recommended heel gap on an ATK World Cup is 4mm. The tolerances in flat mode are pretty tight. Most times the heel gap needs to bump out a mm or so to 5mm to avoid any boot-binding interference as the skier drops their heel.

Minimizing Heel Unit Rotations

Tech bindings have come a long way. Dynafit’s storied and often mimicked TLT Speed or Turn bindings (we’ve seen a renaming of this binding model many times) required spinning (call it turning too) the binding heel to engage the pins, low riser, flat mode, and high riser, respectively. That’s a lot of heel rotating if you are on rolling and varied terrain.

The Dynafit Speed Turn binding, a reliable classic built on the chassis of older Dynafit models. The heel unit must be turned each time to engage pins, low riser, high riser, or flat mode.Photo: Lou Dawson/loudawson.com

Ski-mo racers look for efficiencies in transitions. They are racing after all. Backcountry skiers, hopefully, aren’t racing the clock or that other guy’s Strava segments. But efficiencies while transitioning are always welcome.

Nowadays, all binding companies offer a speed touring binding (not a pure race category binding) with similar heel unit features as their race cousins.

The PLUM R170 heel unit, pins forward. With this race inspired binding, turn the heel into three different orientations to use the low, flat, and high riser modes, respectively

Some race hybrid bindings like the PLUM R-170, the Dynafit Superlite 150, and the Kreuzspitze GT 2.0 require turning the heel into three orientations to use the low, flat, and high riser modes, respectively. Other slightly heavier iterations of the race hybrid binding, like the ATK Haute Route or the BD Helio LT 200, require a single 180 degree heel unit turn to use the low-riser (over pins) or the flat mode with the option of deploying the higher riser.

Why Skin with Pins Forward?

At the bottom of the slope you’ve just skied (or maybe you are just starting out), pop the ski off and apply skins. There’s no need to rotate the binding, just flip the riser over the pins, step in, and pull up on the toe lever (this secures the toe unit more firmly when skinning). Do this for the next ski, and start skinning. The riser used in this orientation is often not too high. Ok, skin to the top.

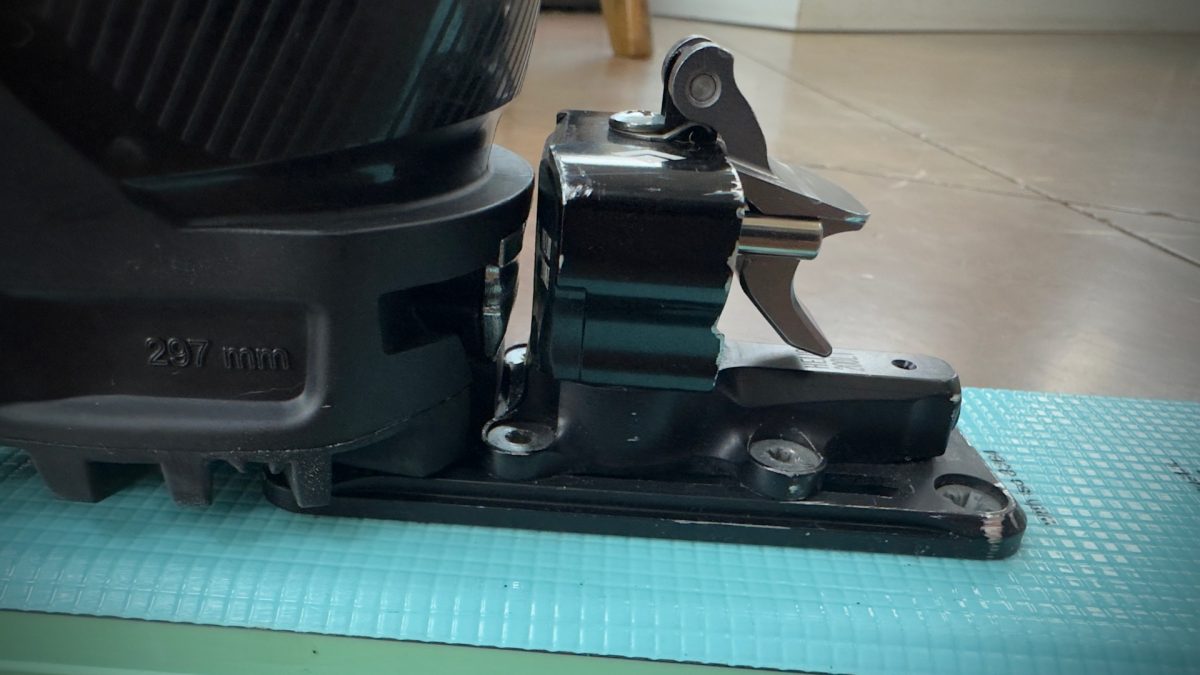

The BD Helio LT 200 (rebranded ATK binding with similarities to the Haute Route 10) with the low riser flipped over the pins.

In this scenario, with the riser over the pins, it helps to have a boot with a large range of motion: something, say 60-degrees and greater.

At the top, rip the skins. If you can do that without removing your skis, you’ll find this next move saves a bit of time at transitions. Skins are ripped, flip the riser back and stomp down into the pins. Adjust from walk to ski mode on the boot (usually a flip of a lever), secure the buckle, BOA, Twistfit, powerstrap…you get the drift. Repeat for the other foot. Then descend.

The upside: Fast transitions. And there’s no binding rotation at the top (or bottom of the run) in the riser-over-the-pins orientation. Quick transitions don’t mean this is a race. It can mean less time fiddling with skins, boots, bindings and time to take a sip of tea, take in the view, or another means of decompressing.

The downside: without rotating the heel unit, you are limited to a lower riser with some bindings. With the right boot, this is not such a downside.

Why Start in Flat Mode?

Oftentimes we transition at the bottom of a run where the slope angle decreases significantly. By beginning in flat mode on a binding like the ATK Haute Route, you can ease into the skin track with longer strides. As the angle kicks up, it’s easy to flip the high riser into place.

The BD Helio LT 200 rotated 180 degrees from pins forward. In this position the skier has access to a flat mode and a high riser.

The upside: It’s super quick to transition between flat and high riser mode (the high riser on this binding isn’t that high). In rolling terrain or on a long traverse where setting a lower-angle skintrack is possible, moving between flat mode and a riser is truly fluid— which is more efficient.

The downside: If you are wearing a sizable pack, like on a multi-day traverse, bending over to twist the heel when you are transitioning to descend can be a pain. Most often, I tend to pop my ski off, twist the heel to pins forward, de-skin, and prep for turns.

Find what works for you. But pins forward with the low riser flipped over the pins can make transitions part of the flow state. Maybe that’s hyperbole. But it will make transitions faster.

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.