(This post sponsored by our publishing partner Cripple Creek Backcountry.)

The objects at hand. Dynafit Radical 2.0 and Rotation ski touring bindings are nearly identical, a few key differences.

Building on the venerable Radical series, Radical 2.0 offers a completely reworked heel unit that in our opinion is nearly impossible to blow up, as well as a rotating toe that’s said to make the binding less prone to pre-release. Testing last winter proved that “Rad2”, while fiddly in some ways due to the rotating toe (and not tourable unlocked), is a durable and effective ski touring binding.

Enter the Dynafit Rotation ski touring binding. An upgrade overall similar to Rad2; heel unit identical, important changes in toe unit.

Rotation has an improved toe unit that’s easier to use; it’s otherwise virtually the same binding. In all, a solid addition to the large variety of “free touring” tech bindings that boast integrated brakes, heel units that adjust to ski flex via a spring loaded track, and overall beef.

Rotation has an improved toe unit that’s easier to use; it’s otherwise virtually the same binding. In all, a solid addition to the large variety of “free touring” tech bindings that boast integrated brakes, heel units that adjust to ski flex via a spring loaded track, and overall beef.

Below, I do a bit of comparo as to the differences between Rad2 and Rotation, and segue into describing how both bindings deliver their promise of a strong ride. Please know this is not a review, that’ll come later this winter after we abuse the retail version Rotation.

Before we begin, a few previous posts covering this same subject matter.

Dynafit Radical 2.0 Review

Radical 2.0 Brake Removal

Comparison of Radical 2 with ver 1

And the numbers…

Radical ST 2.0, heel unit, 110 mm brake, 416 gr – 14.7 oz

Radical ST 2.0, toe unit, 230 gr – 8.1 oz (steel wings)

Radical ST 2.0 single binding, total, 646 gr – 23 ounces

ST Rotation 10, heel unit, 110 mm brake, 416 gr – 14.7 oz

ST Rotation 10, toe unit, 208 gr – 7.3 oz (aluminum wings trim 22 grams, nice to see “negative weight creep”)

ST Rotation 10 single binding, total, 624 grams – 22 ounces

Delta and stack height are identical. See this post for numbers.

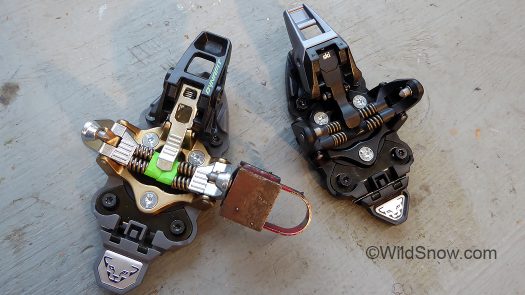

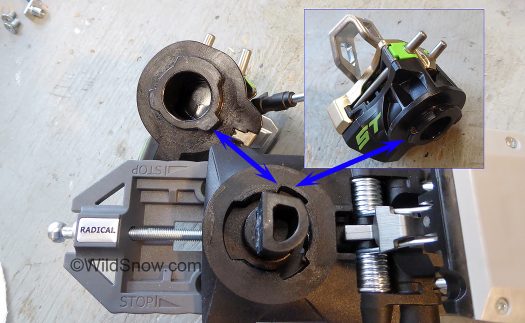

First, let’s get down to brass tacks. Both bindings have a toe that rotates a few degrees. Difference is the Rotation (bottom of image) has a small ball bearing detent that keeps the binding centered while you’re doing things such as clipping in for downhill skiing or locking for touring. Radical 2.0 is a challenge in this regard, as the freely moving toe rotation creates various points of confusion while you’re messing with the binding.

In more detail: Granted, when you prepare either binding for clipping your boot toe, the toe lock lever does secure it from rotating. But as soon as you clip your boot the binding toe can rotate, thus causing your boot heel to possibly shift out of alignment with the binding heel unit pins, as well as possibly rotating the toe off center and making it impossible to lock into touring mode. Latter situation appears to be the norm for inexperienced users — we’ve watched scores of such skiers struggle with the Rad2 binding in this way. We are optimistic the detent of the Rotation binding will eliminate or at least greatly mitigate these issues. Arrow in photo points to the detent.

Rotation underside shown at both left and right, with binding rotated (left) and straight ahead (right), held by the ball bearing detent.

With both bindings, the question: Why the rotating toe? According to Dynafit, this mechanical system allows the boot to absorb shock (essentially, a partial release) without the binding toe pins riding part way out of the boot toe sockets. In the case of tech bindings without rotating toe, every time the boot moves in lateral or rolling shock absorption, the toe pins ride some distance out of the boot toe sockets. Idea is that once the pins are partially out, the system is more prone to accidental release. Pop. Makes sense and can be easily simulated on the bench by moving the boot heel partially through the lateral release cycle and evaluating how much force it takes to knock the boot toe out of the binding toe — comparatively done in the case of both rotating and non-rotating toes.

The burning questions are, of course, is the rotating toe unit truly beneficial in real life use, and are there any tradeoffs other than the added weight? (Engineers will tell you, any time you change part of a machine there are _always_ consequences).

My “rotational” take: I’ve always felt that a unique feature of most tech bindings was that the boot toe fittings “ball and socket” joint provided a modicum of spring loaded resistance and shock absorption. In the case of a rotating toe, this front spring action in partially eliminated as the toe rotates (the springs only engage during the latter part of the release cycle, when the boot finally pops out of the toe unit). My take, could be a wash; could be an improvement.

Anecdotal accounts from binding testers indicate both Radical 2.0 and Rotation clearly have no more problems with accidental release than the original Radicals, perhaps less. Getting a firm read on that is tough without some sort of organized field study, and I’ve not heard any plans for the NTSB to be doing crash dummy testing with ski bindings (they’re busy figuring out how to test self driving cars). Mainly, I’ve spoken with strong and aggressive skiers who are very happy with the binding. So fine. Let’s leave the great rotation debate to the comments, or to the future after more consumer testing and WildSnow bench racing.

(If you chime in with glowing accolades for your Rad2 or Rotation in terms of release-retention performance, we’d be delighted to hear it. But please share what release values you’re skiing the binding with, as pegging the settings and thus essentially eliminating any sort of practical binding release probably makes any performance contribution from the rotating toe a non issue.)

Sidebar. I should mention that an ongoing problem with tech binding ski setups is boot toe fittings that don’t smoothly release from the toe pins, due to manufacturing defects or wear and tear. I’ve been told by insiders that getting the boot-binding tech interface right takes it to the limits of metallurgy and manufacturing. The rotating toe mitigates this challenge. Once the boot is partially through a lateral release cycle as allowed by the rotating toe, the system would have to be highly compromised for a release not to occur. Considering that, even with the rotating toes, all boot-binding combinations should be bench tested for releasability before being skied.

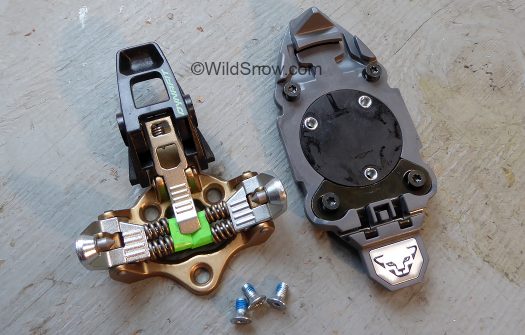

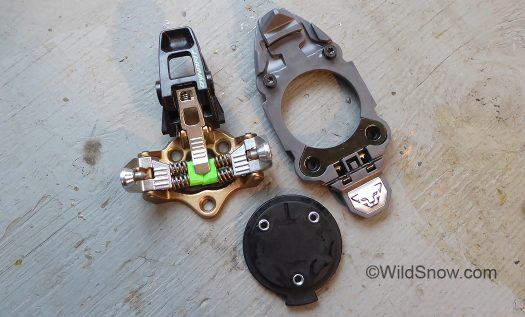

I stripped down the Radical 2 toe to show how the rotation works. I liked the Rad 2 colors better for photos, and didn’t want the Rotation detent ball bearing rolling across my studio floor into a crack.

After the toe unit is demounted, turntable easily comes out. The design is nicely minimalist for something with moving parts.

Let’s get down to an interesting difference. Radical 2 (left) has steel wing arms, testing magnet attached. Rotation (right) arms are aluminum. Result is Rotation toe weighs 22 grams less, clearly the main reason Rotation bests Radical 2 in the weight contest.

It could be argued that the most important improvement to these bindings, over earlier Radicals, is how the heel unit is ‘bayonet mounted’ on the base plate. Both the Rotation and Rad2 are the same this way. I covered this feature in a previous blog post, but it’s worth more exposition.

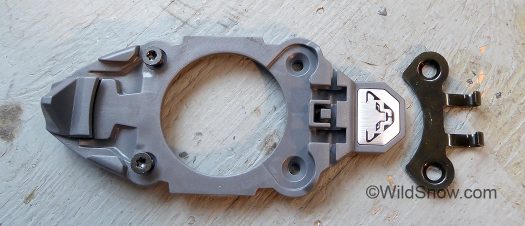

Rear binding housing (at top of photo), has obvious flanges corresponding to slots and flanges in the base. Rad2 and Rotation are identical in this. Idea here is total resistance to the housing getting pulled up off the base spindle –a rare but nonetheless real event with many earlier tech bindings. I like this design, it’s smart and doesn’t seem to add weight. Deal maker? Probably not unless you tend to pull bindings apart. In that case, would your name be Igor per chance? Send photos.

While we’re on the subject of heel units, both Rad2 and Rotation use oversize lateral retention spring and cap shown on left in photo. Spring to right is the common size nearly all previous Dynafit bindings used. Sizing this up is probably a good thing for a free touring binding, though not necessary for the average “moderate” user.

I like this. Rotation (top) has a thicker slightly higher trigger (~ 1 mm) than the Rad2 (bottom). Combined with the rotation detent, this should make a noticeable difference while clipping in, though it might create a bit of a hair trigger for boots with thick soles. Easy to tune by carving small amounts of material off your boot sole. We’ve been dealing with this sort of issue for years. Also, specific to removing sole material, see this post.

Heel units are structurally identical as far as we can tell (It’s my understanding that Rad2 has been sold in both gold accent and all black), only consistent difference in appearance is probably the badging.

Clones. Baseplates even have the same part number stamped on the bottom. Rotation to left, Rad2 on right. (Pictured Rotation has 120 mm brake, Rad 2 is 110).

Me likey, boot length adjustment screw on both bindings accepts both 8 mm socket or T20 torx (same as mount screws). We waited years for this.

Back to the bottom, of the base plate. Both bindings have a fairly beefy spring that compensates for ski flex pushing the binding heel unit against your boot heel. Many tech bindings take care of this by having a gap between boot heel and binding. While that solution is elegant in simplicity, it can be problematic in terms of friction and lack of range. Our understanding is that in order to receive TUV certification to ISO/DIN standard 13992, the bindings need to have this spring feature. Yes Virginia, both Rad2 and Rotation are “DIN” certified. How important is that? You can inform yourself here, and with more DIN/ISO info here.

Super strong top plate is ‘keyed’ into the lower housing, both 2 and Rotation are identical in this regard.

Conclusion: Both bindings are virtually the same. While clearly a good idea in terms of shock absorption performance, the toe rotation can be problematic. You can’t tour with either model’s toe unlocked, and clipping your toe in can be tedious. The Rotation model significantly mitigates the tedium due to the toe rotation detent — this is the only major difference between the two grabbers. Nice the alu wing arms of the Rotation save 22 grams per binding. We like the rotation’s slightly taller toe “trigger,” this will go unnoticed by most people but saves tuning work for the outliers with boots that don’t interface quite right. As mentioned above, while this is not a review, I’m comfortable giving Rotation a 98% of two thumbs up base on this bench race. We’ll see if the last 2 points can be added after we test the retail version binding this winter.

Shop for the Dynafit Rotation.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.