2015-2016 Nano is virtually the same, has protective coating over the white coloration and a stronger binding mount plate, all for a price of about 15 grams.

We got our hands and feet on a pair of 2015-2016 Nano. Wonderful. La Sportiva did not fix what worked. The pair of planks average out at 1215 grams each, virtually same weight as before (1,200 grams). Nearly zero weight creep! Freshman version chipped easily through the white paint topskin. New version has a plastic coating. Overall finish is decent and they ski just like the originals reviewed below. I used the tip hole for mounting a Montana skin tip anchor. Word from La Sportiva is they’ll be “branding” Kohla skins to go with their skis. So long as they don’t force customers into Kohla’s “Vacuum” skin adhesive, that’ll be ok. The Vacuum glue is more a specialty item; in our opinion it’s not tacky enough for colder temperatures.

There have been some questions about Nano’s durability. My take: the market is wanting a genre of skis that sacrifice some durability for weight savings. Nano is in that class. Know what you’re using, and use it appropriately. Skis such as these are not designed for things like resort bump skiing, or backcountry conditions such as frozen avalanche debris. They’re human-powered powder and corn harvesters, pure and simple.

Original review:

One of many test days on the Vapor Nano, this time on frozen and semi-frozen corn, Independence Pass Colorado. Click images to enlarge.

If you human power your skiing, the bias is there. Hand us glycogen craving maniacs a pair of skis that hardly register on the scale; we want to like them. A lot. You have been warned.

Consider La Sportiva Vapor Nano. Presently these planks rate as our NUMBER ONE lightest ski for running surface vs. weight, and 3rd lightest on our ski weights vs length. Those weights are amazing on paper — and in real life on your feet or backpack you notice a very real difference in comfort and efficiency.

I’ve used the Nano for quite a few days now — the feeling they give going uphill is nothing less than endorphin inducing. Sometimes I just laugh at the audacity of it all. I mean, how light in weight is this stuff going to become?

Consider Moore’s Law, the simplistic algorithm of tech stating that computer processor power will double every two years. Moore’s Law has held true for decades and is resulting in a bounty of cyber induced wealth we’ve only begun to experience. Is there a Moore’s Law of ski weight?

My favorite touring ski in 1987 was the Dynastar Yeti, a classic European style mountaineering plank that incorporated Dynastar’s race technology. They were super edgy on steep hard snow, something I needed at the time as I was in the middle of skiing all the Colorado 14,000 foot peaks and had to use a plank that would get me safely down some icy stuff I’d normally not bother with. You’ll laugh at this unless you’re a skimo racer: dimensions of the Yeti in my collection is 88/70/79. That was considered somewhat wide at the time, with alpine ski waists hovering in the mid to upper 60 millimeter range. Now, all skis from that era appear ridiculously skinny.

(Note, 2015-2016 180 cm Nano weighs 1,215 grams, slightly more but not enough difference to change my take on halving times for weight.)

In any case, I entered the Yetis into our ski weights comparo chart. They score at a kludgy 108 for surface/weight, while Nano scores 60. To be generous, let’s say that’s 26 years to drop from score 108 to 60, or a very rough halving rate of a quarter century. That’s not exactly the scorching pace of Moore’s Law, but still, we are now cruising around with planks that in the sense of surface area and subsequent performance are about 50% lighter than what we used in the 1980s. For the future, that means that perhaps skis will become about 2% lighter per year (in fits and starts, depending on innovation). I’m not sure I got this napkin math done right, but you get the point. Every few years, the latest touring skis will be noticeably lighter than older models: bounty that keeps on giving.

Circling back to my point of “how light will they become?,” clearly we are not near the end. New materials and designs are on the horizon. Examples: graphene carbon is so strong as to be nearly miraculous (with interesting electrical properties, skis as batteries?), and since the steel edges in a low mass ski are now a big percentage of total weight, design engineering could perhaps come up with new ways to include edges that still worked but saved significant mass.

Trimming length is an easy way to save weight as well. A disappointing consequence of rocker geometry is that skis got longer, but perhaps engineering will result in a reversal of that trend, and those of us who stepped up to 180s or 190s can eventually drop back down five or ten centimeters.

Back to the La Sportiva Vapor Nano. Here we have a ski that incorporates a great deal of carbon, along with modern width and rocker. So how do they ski downhill?

First, it’s important to realize this is a TOURING ski. It is not in my view intended to be a “quiver of one” for those seeking a plank that’ll pound bumps at the resort one day, then slink through backcountry powder the next morning. Second, we don’t want this to be the most durable ski in the universe. We want it to be light. I truly doubt the Nano is as strong as some of the heavier touring and alpine skis out there. So, a simple take: If you want beef, get beefy skis. If you want to enjoy lightweight touring, rock something like Vapor Nano. Accept they’re perhaps on the less durable side of the equation, and behave accordingly.

In terms of skiing down, my observations:

Powder: Plenty fun, a bit less snap than I expected from a carbon ski. I felt the bindings could have possibly been mounted a centimeter back or so from recommended neutral position (more on that below). You can feel the pronounced tail rocker and big tip giving you lots of options in exactly what type of turn you choose to execute.

Hard snow: I tested on frozen corn, always a good way to truly evaluate what a ski does on the hardpan. This is not a hardpack ski. Unless I was in the sweet spot and below a speed limit, I’d get some chattering and that general feeling of ski that isn’t really designed for the situation. I’m not sure how much of that has to do with geometry as opposed to construction. But with 33 cm of tip sticking out there in front, and 27 cm of tail rocker, unless you’ve got the Nano adequately tilted you’re looking at a lot of material floating in space off the snow, vibrating or whatever.

For me this is a non-issue in a ski touring situation as I don’t make a habit of skiing ice, and some detuning of the tail edges did help. If I’m on hardpack, I just ski the plank in a way that works. Usually, that simply means obeying a speed limit. So what if I get to the bar or car 20 seconds later than I would on a different ski? Point here, this is not a hardpack ski — if you need to prove your manhood you might want something more designed for straight lining.

‘The big tip DADDY’, lots of ski floating out there in the ozone, helps in soft snow but does nothing for you on hardpack except vibrate. (That’s a Montana brand climbing skin anchor attached to the tip, in case you’re wondering. I’ve been testing those, they’re working nicely.)

It seems weird for my next point to be part of a review, but more things than weight are changing in the ski world. On hardpack Vapor Nano is NOISY! If you had a long descent of hard snow, it’s not far fetched to recommend ear plugs to prevent hearing damage. Seriously, I’m thinking of bringing a DB meter next time I go out. Sherlock Holmes note: The noise does sound almost exactly like a Goode brand ski, leading one to wonder, are they made in the same factory?

Crud and mank: This is the one area where actual physical weight of the ski can make a difference (as opposed to damping characteristics and such that we sometimes mistakenly attribute simply to the ski being heavier.) So what can I say? In the mank they feel like a lightweight ski. Stay on top of them and keep turning, you’ll do fine. Pick up speed and straightline, not so powerful.

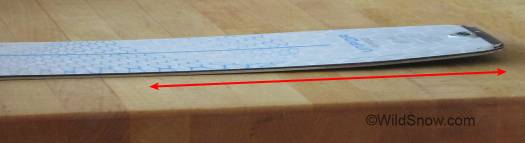

Due to the amount of tail rocker combined with tail protector, you may have up to 3 cm more ski behind your boot than with other models of skis. I cut off as much of the tail protector as possible, resulting in a tail bobbing of about 1 cm, which combined with a remount back 1 cm yields a more conventional boot position. As this ski is unusually light and also has an unusual mount, I’d emphasize a demo day before purchase.

Breakable crust: The big tip and tail rocker help, but the amount of ski behind your foot is fully 3 centimeters or more than what you’ll usually have with other skis. This is probably due to the tail geometry; lots of rocker and taper mean more tail behind the optimal boot location. In breakable crust, all that tail makes it hard to cheat and swivel around and it feels kind of odd during jump turns as well. I think I can get used to it, but it’s definitely different.

Uphill take (with a bit of down thrown in)

Position of foot on ski appears to meld well with the sidecut, and as noted above I found the Nano skied fine (with reservations) at neutral boot position as indicated by factory ski markings. Yet due to the shape and rocker of the tail, once you mount your bindings you’ll have 3 or centimeters or more of extra tail than a similar length ski in most other brands. Perhaps I’m too sensitive, but with my 178 cm testers the added 3 centimeters confused my kick turns. On the down, in manky conditions where the tail fully engaged I felt too far forward on the ski. Again, on both soft and hard snow that was in good condition the mount position felt fine, so this brings up an interesting dilemma. Do you mount in optimal position for the down, or tweak things for the up? Your call, but it’s a question that Nano might bring up for you, as opposed to other choices in skis with more conventional geometry.

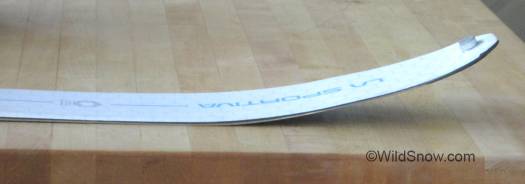

Nano tail rocker is about 27 cm for our 180cm testers. While not a ‘full rocker’ up to the boot area, that’s a significant tail rocker profile and results in the running surface and sidecut engaging in different ways depending on snow type and ski style.

Conclusion: La Sportiva Vapor Nano is a joy for ski touring: incredibly light, still with adequate width for just about any snow conditions. Extra tail behind boot position takes some getting used to, but is there for a reason. White color scheme is ideal to prevent icing and subsequent weight increase. Standard “K2” style tip and tail holes are mandatory — we appreciate not having to drill them ourselves. Recommended as a touring ski (not a quiver of one for resort/sidecountry/backcountry), with emphasis on soft snow but they’ll get you down the hardpack. Our hope is this type of specialized ski continues to be available and not compromised by the needs of the freeride community who have other choices for planks aligned more closely with their needs.

My testers scale at average 1,200 grams per ski (2015-2016 weight is 1,215 grams per ski), catalog dimensions 180 x 130/103/120.

If you want to shop, Cripple Creek Backcountry might have Nano for sale.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.