Hauling sleds through the milk on Kahiltna Glacier, lower part of Washburn route.

May 25, here at the 7,800-foot camp on Kahiltna Glacier we wake up to white. We are “inside the egg.” This is not what you want to see when planning to walk 4 miles along a heavily crevassed glacier. The good news is that it’s not snowing, so it’ll be easy to make out the trail made by many other summit hopefuls, as well as those returning down from the mountain.

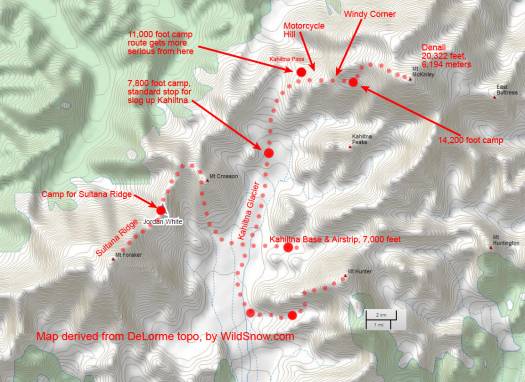

From 7,800 camp the glacier ascends to 9,600 ft (another camp that’s sometimes used), then to the very popular 11,000-foot camp where the route steepens. Slowly but steadily we trudge our way up the hill with our hated sleds behind us. It’s nothing to brag about, perhaps even dumb, but we’re moving everything in one carry. Normally climbers do two or even three carries to move between 7,800 and 11,000. Strength gained from being up here and working so hard allows us to do this, but we are probably over trained and need rest. Perhaps we’ll get a break at 14,200 feet where we’ll stage for the real climbing and skiing. But for now, the route must progress as we don’t want to miss any weather windows.

The climb is surreal due to the cloud that surrounds us like a gigantic fuzzy white blanket. Having about 45 ft of visibility means we have no idea of our progress. Nor can we tell what’s coming next. Every once in a while something appears in the distance, ghosting closer through the gloom. Descending groups silently slip past us. We slowly pass a group of three Japanese on snowshoes.

Busting out of the clouds makes the going slightly easier.

Finally at 9,600 camp we break out above the cloud. High clouds still block the sun so it only warms slightly (it can get too hot for efficient travel down at these elevations). Being able to see greatly helps the mental aspect of our slog. Moving along this flatter section feels like a breeze, but at 10,000 ft (just below Kahiltna Pass, see map below) things change. The slope gets considerably steeper, and we’re getting tired. It feels like the weight of my sled has doubled. With every step I give nearly everything I have. Then my ski climbing skins begin to slip on the worn and packed track. My expletives become more frequent, louder and more vulgar with every step.

At one point two Euro styled guys pass us with maybe a quarter of the gear we have. I silently loath them, but also very much want to be them.

View from 11 camp. Worth the pain. Yep, that’s Sultana.

When camp appears over the crest of the last steep section, I feel like crying out in joy.

11,000 ft camp is like a small metropolis compared to our time on Hunter and Foraker. We find a vacant plot and quickly put up our tent. Once all the work is done I’m finally able to take a good look around and see the beauty of the place we are in. We are walled in on three sides by huge ice walls. Down valley opens up to the top of the cloud we had worked our way through earlier. The soft light of the Alaskan night seems to make everything shine. Amazing how a good view will make all the previous pain recede in memory.

(‘Ski The Big 3 is an Alaskan ski mountaineering expedition cooked up by four deprived (or perhaps depraved?) guys who never get enough ski and snowboard mountaineering. Aaron Diamond, Evan Pletcher, Anton Sponar, Jordan White. The idea is to ski Denali, Mount Foraker, and Mount Hunter all during one expedition. They’ve got six weeks worth of food and enough camera gear to outfit a small army. Should be interesting. We wish them safe travels, we’re enjoying being their blog channel.)

WildSnow.com guest blogger Anton Sponar spends winters enjoying the Aspen area of Colorado, while summers are taken up with slave labor doing snowcat powder guiding at Ski Arpa in Chile. If Anton didn’t ski every month and nearly every week of the year, skiing would cease to exist as we know it.