A boot company goes for it with innovation. They deserve respect. We had the honor of being the first journalists (bloggers sometimes call themselves that, though we get scolded by the “real” scribes) to cover Scarpa F1 Evo ski touring boot. That was during our epic European gear journey last January — when in truth I was surprised we even got that blog post done in between the flowing prosecco and scurrying waiters delivering four course meals that made any other victuals of the world seem inedible.

While the Evo was indeed radical, in truth the Scarpa Alien 2.0 was the jaw dropper that used up our blogger energy. So perhaps we’ve not been giving Evo the blogination it deserved, the poor little thing. In an attempt to redeem our carbon composite transgressions, check out a few details regarding Evo. Oh, and I’ve skied them enough times for a take — yes Virginia, in the end that’s what is important. Read on, oh esteemed WildSnowers.

Scarpa F1 Evo. Always fun to take things apart. Per a foundational design philosophy at the Asolo “Fabbrica di scarpe” where dystopian injection molding machines cause chemicals to become ski boots, let there be removable fasteners wherever possible! In this case, the cuff comes off with a bit of effort on the hex keys, with the lower tongue screwed on as well, along with the main cuff buckle Velcro (actual cuff buckle is riveted). Here at WildSnow we almost worship boots that we can take apart. Omanepadmehum, or in Western terms, Praise the Lord, I can mod these boots! (This has been heard sincerely voiced in the WildSnow mod shop; it is not blasphemy, though one has to assume that the entity upstairs might have better things to do than fiddle with boot fasteners. Om. Click all images to enlarge.)

First thing about Evo F1, it has the commodius Scarpa toe box. More, this is NOT a DIN compatible ski boot (cheers) but rather is totally optimized as a tech binding compatible boot, including Dynafit certified tech fittings. With my skinny feet and ankles I definitely had to downsize from the 28 cm scaffo I tested. It was comfy, but not the semi-performance fit I’d want to end up with for keeps. Takeaway: The thin plastic of these shoes makes them look minimal, but they still have toe space to keep your feet from the fangs of Jackson Frost.

For grins, these are the cuff fasteners. To be cleaned and replaced with blue or red Loctite but of course. (Thoughts: As many of you know, I used to work on my 1947 Willys Jeep rock crawler for wrenching amusement. WildSnow is a full time job — no time for such trivial games. Instead of Jeeps I take apart ski boots. Funny where life leads you. At least I have the tools. If a normal hex wrench won’t do the job, my 113 N/m torque rated impact driver has just the right touch — and makes me glad Scarpa customer service is so kind with spare parts. Whoops.)

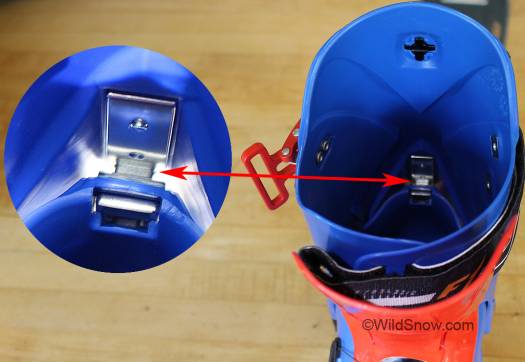

Now, to the nitty gritty. What sets Evo F1 apart from the vast sea of ski touring boots is the “auto locker,” (as we’d term it if we were fording a Siberian river in our global exploration truck). In this case, the “locker” (branded as the Tronic No Hand) is simply a clever device that causes the boot to cuff-lock into downhill ski mode when you step in to your tech binding heel. There is no manual switch. And yes, when stepping out the boot automatically reverts to touring mode with a free cuff. How does this miraculous behavior occur (om!)? Simple, as shown in photos above and below, that little metal tab we point to in the heel fitting is pushed up with the binding heel pins when you step in. This in turn pops out the touring lock nib inside the boot shell behind the upper arrow. Incidentally, upper arrow also points to a lug on the boot with two screws you can back off for a small but meaningful cuff lean adjustment.

Details. In this shot I’m pushing the steel ‘trigger’ up with a chopstick (for contrast, don’t get any weird ideas), which in turn cause the nib to protrude as pointed with arrow.

Another view of the cuff lock system. Binding pins push up the actuator pointed out by right arrow, which in turn cause nib to pop out and engage small slot in the cuff.

Auto locker revealed. Quite simple, really, like all basic machinery should be. Shown here in the unlocked mode, the nib is loaded by a leaf spring and pushed towards the inside of the boot. When the push rod-bar moves up, it moves the leaf spring which in turn moves the nib so it protrudes out the other side of the housing and thus engages the cuff.

View of Tronic No Hands auto cuff locker, engaged. We’re concerned there may be too much of a gap between cuff and shell, long term testing will evaluate this.

Auto locker tends to distract. Yet a key idea here is that you should be able to fine-tune the boot cuff buckle and power strap so you might not have to tighten for the down — or at least have it to the point where you just flip the buckle closed and leave the power strap as is. I tested the system for doing this with mixed success. If I tightened everything to the point where I truly wanted it for downhill, it was all a bit tight. Nonetheless I could compromise and make it all work. Cool to strip skins, step in, and ski. Zero fiddle factor. Obvious downside to this for some of us is you can’t lock the cuff manually, say while skiing down with skins still on skis, heel unlocked. Yeah, I know, some of you would NEVER do that. Thing is, we actually ski that way quite often to get down to our cabin in winter. I could adjust to the Evo for this, but one has to wonder if a small manual cuff lock could have been built in?

Important note about the “No Hands Tronic” auto cuff lock on the Evo: Know that when your boot comes out of your binding, your boot cuff is simply not locked; you will be in touring mode. While that’s perhaps a desirable convenience, one of the most common pre-release modes with tech bindings is an upward release at the heel resulting in “insta-tele.” Often when this happens you can feel it and just step back down into your binding heel without falling, but in doing so you need your boot cuff to stay supportive. With Evo, you’d end up with no rearward cuff support in this scenario, and it would be much more difficult to recover.

Check this out! Well known vulnerability of nearly any tech fitting equipped boot is possibly weak attachment of rear fitting. In this case, the Scarpa fitting has a wider upper area to allow for two extra anchor pins, as well as two pins in the center area, for a total of FOUR anchor pins along with the attachment screw! This is major. On the other hand, we still don’t understand why the rear fitting is not through-bolted into the boot instead of being attached with what is essentially a #10 wood screw. We thus still recommend checking screw tightness occasionally throughout the season. With high-use boots, we recommend removing the fitting, then replacing with everything bedded in epoxy to eliminate micro-movement.

Liner is your usual nice Intuition brand inspired work of art. Not much to say here except you won’t find anything better, and as always we like the lacing option though we’d prefer the lace loops to be stronger.

One essential thing that all boots boasting good cuff articulation should have: A supple flex zone at the ‘break’ where the cuff flexes. Scarpa uses a soft neoprene material for this, backed up by a limiting strap to prevent damage from overzealous fitting. We’d like the limiting strap to be shorter, but in any case good that it’s there.

Beyond the autolocker, I’d say that the stiff carbon yoke that connects the cuff pivot to the lower shell (scaffo) is the most effective part of the Evo design. This is not a new concept in how to stiffen ski touring boots while trimming mass, but Scarpa invokes this nicely by molding the carbon into the regular boot plastic while leaving the black beefy stuff exposed, no doubt as a design statement. This is not cosmetic, however you can squeeze the boot with your hands and feel the added beef.

Stiff carbon composite ankle yoke as visible from exterior. Note the plastic boss protruding from the scaffo that the cuff rides on — we think this creates a situation that’ll accept the B&D Ultimate Cuff Pivot (UCP). So for grins we fit up a UCP as much as possible without cutting on the boot; turns out all a UCP would need for complete install is a slightly thicker shoulder bushing to fill up the slightly wider pivot hole in the cuff, and a bit smaller diameter of the backing washer that sits inside the boot.

Considering the carbon yoke, Boa and all that…how do they ski?

In touring mode Evo felt “modern light” in weight. Ditto for cuff articulation; no problem there. This is definitely a desirable boot if you’re talking touring comfort. Indeed, if you have chronic fit problems, Scarpa’s Evo last might be enough of a departure from the norm to be worth looking at for something that finally works for you. The Boa system looks unusual but I’m here to tell you it is effective. A boot with thin plastic such as Evo suffers from weird distortions when closed with the ancient technology of cam buckles. Using the Boa cable winch, you get a nice even snugging around your foot. Bonus, you can reach down and change overall pressure in seconds. Downside? No individual adjustments for lower shell pressures as you’d perhaps receive with a couple of buckles; solution, do your homework with liner molding and fitting (as you must with a three-buckle boot).

Boa works. Me likey. Anyone else tired of boots that close using 50 year old technology? Boa is modern, but has to be done just right or you get a fail. Evo tested right.

Downhill performance was predictable for this sort of shoe. You are not not massaged with much in the way of progressive flex, but once the hatches are battened down you do have a reasonably responsive connection between your leg bones and ski edges. A trend I noticed this year is more and more skiers have realized that with modern ski technique they don’t need a lot of cuff flex in downhill mode. “Strap me in, hold me tight, and don’t let go!” is more the mantra. My theory is that skimo racing is finally making inroads into ski touring gear choices. As in “I can ski this boot and it’s a pound lighter, so what, it feels different?” In that sense, Evo will work. Only don’t expect it to ski like an overlap alpine boot.

Nonetheless, one is led to ponder what F1 Evo would feel like with an ultra rigid fiber composite cuff paired with the ankle yoke. I’d guess that could be in the works.

A few more things. Shell does have a boot board — surprising (and appreciated) for this type of low-volume shoe. Tongue is two-piece and provides no significant additional stiffness in downhill mode. This is nothing less than a faustian dilemma. Keep the shell tongue stiff and one-piece, the boot tours worse. Make it two piece, and it doesn’t add anything on the down.

You thus wonder if Scarpa could ever figure out a stiffer tongue with some kind of latching system that would release it for walking and stiffen it for skiing down (attempts at this have been made over the last century, but never to total satisfaction).

Sole is a Vibram brand low-density creation, yet with a bit of higher density material under the toe fittings. Nonetheless, amount of material under the branded and certified “Quick Step In” toe fittings is minimal — as in about 3 mm thick! I wish they’d just go back to using older style tech fittings in boots of this sort so we’d have more sole material to wear out on dirt and rocks. Any competent skier doesn’t need anything more than the old fitting shape. (Do I sound like a broken recording when it comes to touting stuff that tech binding inventor Fritz Barthel figured out about 30 years ago, perhaps before some of you were even born? Sorry, reality strikes.)

Conclusion: An incredibly innovative boot that shows why the scions of Asolo still rule the skier’s world of nylon plastic and carbon composite.

Metrics

Boot evaluated is a Scarpa Evo F1, BSL 304, size 28, scaffo 28.

Total weight per boot is 44.0 ounces, 1246 grams.

Weight of one inner is 8.8 ounces, 248 grams.

Weight of one shell is 35.2 ounces, 998 grams.

Materials: Nylon plastic similar to Grilamid laminated with carbon composite ankle yoke: “Davide’s Secret Sauce.”

Available fall of 2014.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.