Part one of this two-part series explores gear recalls in the backcountry ski/ride community, emphasizing avy beacons. In part two, we’ll dive into former BD CEO Peter Metcalf’s experience leading a gear manufacturer and his thoughts on the current climate of designing and manufacturing personal protective equipment (PPE).

The backcountry affair is no solo dance, it requires a tacit agreement between gear manufacturers and backcountry users: in the gear we trust. Photo: John Sterling

There’s a beacon check pre-ski; all systems go. You and the team are avalanche aware, from a thorough analysis of the avy report and discussion to real-time assessments and routine partner check-ins. There’s comfort in routine and the familiar. It’s part of dialing back perceived and actual risk.

Right here is the stuff of nightmares.

Now imagine sluff and cascading snow sweep a partner off their feet, and there’s audible distress as the slide rips through trees. There’s a near-instant and automatic reflex to simultaneously scan the slide and debris and switch beacons into search mode.

Four minutes transpire. That’s an eternity. Another minute transpires with no signal from a transmitting beacon. Imagine the anxiety. Then there’s probing and a random hit–a body. Dig, clear the airway, and time ticks.

All this isn’t far from the reality of Christina Lustenberger, Ian McIntosh, Sam Smoothy, and the buried skier Nick McNutt back on March 9, 2020, much of which was documented on social media.

The incident, which McNutt survived, figuratively snowballed. What appears to be undebatable is that the lock function on the search/transmit switch malfunctioned. In McNutt’s case, the beacon was fixed in transmit mode and secured in a chest harness, but it switched modes due to a design flaw. It took until April 12, 2021, for the line of beacons to be recalled.

The perception remains that Pieps and Black Diamond Equipment (owned by the same umbrella company) dragged their feet before ultimately making the recall official. In the fast-moving social media ecosystem, that’s too long. And even considering if we could time-machine back to a less content-rich pre-IG era, the time that transpired between identifying the flawed PPE’s issue and action that satisfied some in the community was an eternity.

Looking beyond the immediacy of the March 9, 2020 nightmare and the lessons learned from backcountry users and PPE manufacturers, what becomes clear is that as consumers, we rely on the outdoor industry to act in good faith. In turn, those companies likely trust users are well informed and schooled in best practices, for example, when using PPE like beacons or avalanche airbags. It’s a dance of complicit partners. Users can choose not to buy a product. Companies can choose not to design, manufacture, and sell some products. The bottom line is no one should die or get injured when selecting to use PPE sold on the open market and meets specific codified safety benchmarks due to a design or manufacturing flaw.

This spring, BD/Pieps issued a beacon safety notice (not a recall) due to “malfunctioning electronic components that may prevent it from switching between SEND and SEARCH modes.”

Then a few weeks ago, BCA recalled some specific Tracker4 beacons, with the company stating, “the reason for the recall is a switch plastics production issue that may result in the switch falling off the transceiver. If this occurs, the user would not be able to turn the transceiver on and off, preventing the ability to transmit or search for a discoverable electronic signal in the event of an avalanche.”

There are so many moving parts when thinking about bringing PPE to market and then having those products used by the masses in an environment as dynamic as the mountains.

Finding a path in a dynamic mountain environment.

Peter Metcalf helped launch Black Diamond Equipment in 1989 when Yvon Chouinard put Chouinard Equipment into bankruptcy. Metcalf led BD for more than 26 years and retired in 2015. We spoke last week not specifically about the BD/Pieps transceivers but about what he learned while leading a company and navigating recalls.

“Most of the companies out there doing work today have been around for a while,” said Metcalf. “I think that most of them have integrity. They’re wise. They have quality assurance, quality control, good engineers, and everything, but none of us are immaculately conceived. And even with the best systems, as we saw with the Space Shuttle, and Boeing’s initial disasters with their recent [Starliner] rocket until recently, you can make mistakes that you just can’t see, no matter how much testing you do.”

Metcalf added that problem-solving from the company’s perspective is not uncomplex; they too have a responsibility to act quickly, but according to data-driven findings.

“The key is that you have to respond as quickly as you can,” stated Metcalf. “But also you don’t want to respond instantly with faulty data, innuendo, lack of factual information; you’ve got to research and to understand when you get something back that’s broken. You got to look at it and ask, is this a quality control floor? Is this a quality assurance floor? What is it? Is it ubiquitous to a lot of the product out there? Is everything going to fail, or is some of it going to fail? You know, it’s not a no-brainer to figure out what the hell is going on.”

My experience with recalls is limited. Back in 2018, my Ortovox 3+ beacon was “precautionarily” recalled for a software issue. It’s been a bit; I believe I opted for a new 3+ beacon sold to me at a discount. In the non-PPE realm, I’ve had two skis snap, both lightweight: A 2015 Dynafit PDG and first-gen La Sportiva Vapor Svelte. Each manufacturer sent a replacement. I can imagine, in some circumstances, that having a ski snap could be catastrophic. In my case, one ski broke while skinning, the other while skiing cushy corn, where my slide ceased quickly. But, I was reminded how much we trust these companies and want to trust them.

The recent beacon recalls are only the latest among many recalls in the industry. I found myself on safeproducts.gov, a site run by the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) that allows consumers to file unsafe product reports, businesses to register and receive information about dangerous products, and a search engine to scout out those products.

Typing in the general term “ski boots” reveals numerous personal reports of defective equipment and official recall notices for gear we rely on as backcountry users. There’s a 2017 report of a failed pin on the ski/walk mode on a Scarpa Maestrale RS ski boot. Following the published timeline, the boots were originally purchased in 2014, with the incident date occurring on 12/11/2017. According to saferproducts.gov, the report was filed two days later, with the company (Manufacturer/Importer/Private Labeler) notified on 4/5/2018. There was and is no associated recall.

In November of 2019, in an unrelated filing, Scarpa recalled the Fall 2017 Maestrale RS and Maestrale men’s ski boots (with specified SKU numbers) due to the potential for boot shell cracking. According to the Consumer Product Safety Commission, Scarpa received 605 incidents of boot shell cracking with no associated injuries. You can read WildSnow’s initial treatment of the recall here.

But, like Lou Dawson writes in his exploration of the Maestrale recall, and something that remains true, “as always, we applaud any ski touring gear company going all-in on a recall instead of playing games with PR, customer service, tired euphemisms. Nothing is perfect. Our loved ones and friends use this gear. If there’s a problem, I want it zeroed. Seeing SCARPA own up to the imperfections and make it right is key. They’re doing it. They’re a good company who deserves our support.”

***

So what about transceivers and recalls?

In 2005 Ortovox recalled the M1 and M2 transceivers. Ortovox sold approximately 15,500 units between January 1997 and July 2005. They enacted the recall since “batteries in these devices can become dislodged when the transceiver is struck sharply.” The recall notice on the CPSC site states users filed three reports of malfunctioning beacons with no related injuries documented. Ortovox asked for the devices to be returned so they could fit them with new battery doors.

Ortovox also recalled their S1+ beacon in 2015 and their 3+ in 2018. The CPSC claims neither recall had incidents or injuries associated with them.

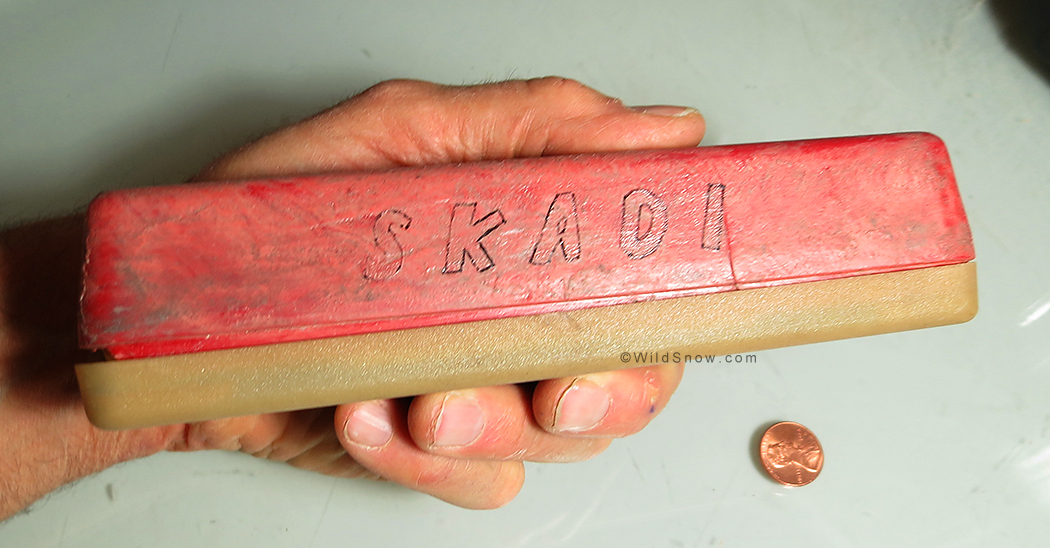

In 1968, the first functional transceiver was developed by a Cornell University initiative. The Skadi unit was known as the ‘Hot Dog’ for obvious reasons.

In 1968, the first functional transceiver was developed by a Cornell University initiative. The unit was called the Skadi and became commercially available in the early 70s. Years later, during the winter of 1997-1998, BCA released the first multi-antenna or “digital” transceiver in the Tracker, which unequivocally was a game-changer.

According to BCA founder Bruce Edgerly, the primary risk he and the nascent company faced was financial. The Tracker met ETSI standards, a set of German-based European standards that test and certify equipment.

“The transceiver industry is heavily regulated by the European standards community, so there’s a huge barrier to entry which keeps out any kind of tenuous designs, it costs a lot of money, and it’s very time consuming to get the certification,” said Edgerly. “We knew we had to meet those standards. And we had to design it to meet the standards, which is very engineering intensive. And so the development process was probably a bigger risk than anything else, just the cost of it. We knew that there would be no question when we introduced the product that it would pass all the tests.”

Edgerly explained the company went so far as to exceed some European standards like the mandated 1m drop test; BCA designed the Tracker to withstand a 2m drop.

Companies like BCA, said Edgerly, know the odds of filing for a recall are greater for a company making life-saving equipment than for a company making snowshoes, for example. With that in mind, manufacturers understand how much a typical user will pay for a transceiver and that product perfection is likely elusive; ultimately, affordability becomes a barrier to zeroing out any potential flaws.

“It’s hard to design a perfect product and make it affordable,” said Edgerly. “The biggest complaint we’ve always had is how expensive transceivers are. There are tolerances in manufacturing. And the more transceivers you make, the more those tolerances are going to stack up. And once in a while, there’s going to be some kind of compromise. So it’s a bit of a numbers game; the more plastic parts you shoot, the higher the probability that some of the tolerances are going to stack up just perfectly to create a weakness. In the old days, there wasn’t enough volume, really, for the probabilities to reach the level where there would be a tolerance stack-up to create a faulty product. Now, to create a product that has 0% chance of failure, where all the tolerances are completely eliminated from the design, it would be a $10,000 transceiver.”

A screenshot from the CPSC’s site with the Fast Tracks Recall information laid out.

The CPSC has established conditions that, when met, require manufacturers, importers, distributors, and retailers to report defective products. The key provisions relating to a flawed transceiver, in my estimation as a non-lawyer, are these:

– A defective product that could create a substantial risk of injury to consumers;

– A product that creates an unreasonable risk of serious injury or death

For BCA, their recent May 26 Tracker4 announcement (dated June 2 on the official recall) was their first time issuing a CPSC administered recall. According to the official recall notice, roughly 9000 units were sold in the US, with an additional 450 in Canada. Further, 14 incidents of broken switches were reported to Elevate Outdoor Collective, BCA’s parent company, with no related injuries or deaths documented.

This recall, like the 2021 BD/Pieps recall, was categorized as a “voluntary recall” and was initiated by the company. For comparison, according to the 2021 CPSC BD/Pieps recall documentation, Black Diamond “received 65 reports of the transceiver modes switching unexpectedly while in use. One death and one instance of a skier getting caught in an avalanche who suffered a broken arm and minor injuries were both reported in British Columbia.”

One dynamic to factor in as a consumer wanting and even demanding expedited action from an outdoor company is this: the gears of a behemoth like the CPSC are relatively slow, and movement, once the CPSC is involved, will likely be slower than a company acting on their own. The CPSC requires internal documentation from the manufacturer; they then evaluate and derive a “corrective action” response, which may not include a recall.

The CPSC process takes time. From the company’s standpoint, Page 8 of the CPSC Recall Handbook details when a company is required to report a non-compliance issue. The reporting timeline, at first glance, appears quick. The verbiage includes reporting issues “immediately” and within “24 hours” once the company concludes they have a flawed product and it meets any one of the conditions set forth for mandatory reporting. The CPSC also provides other timelines for reporting parties to conduct their internal investigations; the CPSC claims 10 working days is a sufficient and reasonable time for an internal investigation but, sometimes, allows for more time.

Edgerly said, in the case of BCA, it’s simply about seeing patterns.

“It’s not just one-offs; we just started seeing the same issue; it doesn’t have to be many,” he said. “I would say replication is the key concept. We might get calls from people who have things happen to their transceivers, but if you can’t replicate it, then it’s hard to justify action. But when you can replicate the problem, that’s when it starts to become a pattern. As soon as we figured out that we could replicate the switch breaking off, that’s when the red alert happens.”

BCA’s investigation and testing narrowed down the problem with the Tracker4 to two batches of plastic from a specific supplier and a run of transceivers manufactured after June 1, 2021.

We have a partnership with the manufacturer in a not so indirect way. Our obligations as consumers are many if we uphold our side of the tacit agreement. At a minimum, I suppose we must know how to properly use something like a transceiver in a simple scenario. But you and your partners must be comfortable with this low-bar baseline.

“You should be able to use [a transceiver] out of the box, and we’ve had that happen,” Edgerly said. “But you’re not always going to have a simple scenario. There could be more than one person involved. There could be issues with terrain. There could be issues with electromagnetic noise in the area. There could be issues with rogue signals, when other people are transmitting that aren’t buried. There could be issues with overlapping signals. All these things are kind of boutique scenarios that we don’t expect users to learn about. But why? Unfortunately, I don’t think most people envision worst-case scenarios, they just envision what they did in their avalanche course, which is probably a single burial in a meadow somewhere. Usually, it gets a little more real than that. And in real life, there’s really no substitute for going out there and practicing the worst-case scenarios.”

The dance, built on trust and a willingness to explore, continues.

Recalls or not, skier/rider trust with PPE manufacturers is critical. We want to believe that in both simple and more complex situations, which some readers have first-hand experience with, the safety tools do their part. Even under the best real-life situations, the outcomes considering avalanches can be grim. I cannot imagine scrambling around on a debris pile probing aimlessly, searching for any signal, swearing my partner’s beacon was transmitting during the AM beacon check.

The dance I mentioned between PPE manufacturers and consumers is not the free-form twirl-fest you might see (or even hopefully partake in) at a jam band show. In contrast, I imagine a highly choreographed dance where the mind-body aligns precisely—-something like the deep trust of two ballet dancers coordinating a complex lift.

The lift is heavy from both a manufacturer and end-user perspective. But in the field, when it hits the fan, that lift, considering the use of PPE, should be near effortless.

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.