Michael Pokress, Pyramid Peak North Face Right 1976. “Pokey” was one of the 1980 plane crash victims for whom the Friends Hut was built.

Looking back on your formative years can be amusing. Dating? Perhaps best to not think about it. School? Boring and downright painful. Winter mountain climbing? Uncomfortable, fun to reminisce, and never (or at least seldom) boring.

In 1976 myself and a few other Aspen locals we’re trying to pretend our section of the Rocky Mountains was one of the great ranges. We got close to our fantasy by climbing big rotten faces in the middle of winter storms, at altitudes around 14,000 feet. For some reason, the north face of Pyramid Peak got most of our attention — probably because it was the biggest darkest and steepest thing around.

This first successful foray (there were many failures), covered in the old Aspen Times article reproduced here, was a new route that followed an obvious weakness on the right side of the face. Our line exited some distance below the summit so I’m not sure if calling it an ascent of “the face” was accurate — but it was a new route and a fine adventure for us three boys. Later, myself, Kennedy and Steve Shea went back and did a more direct line in winter that reached the summit block then exited to the west ridge. I count that one as a complete face ascent though it did till exit rather than being a “direct.” The summit block is probably climbable if you can take the risk of being knocked off by a loose rock. We didn’t think much of that option and subsequent climbers have apparently felt the same way.

During our second time up there we bivouacked at about 13,800 feet elevation on a ledge below the summit. The storm we’d been climbing through for a couple of days cleared up, and we sat there like we figured our heros in the Alps would do, Bonatti!, peering over the hills below and feeling a mental and perhaps even spiritual glow from having done the work to gain such a perch.

Those early climbs developed lasting friendships, as well as opening my mind to potentials I didn’t know I had. As I always say, freezing your fingers and toes off isn’t what everyone needs to find human potential, but some of us choose that path and that’s our part in the fray of life. Hopefully we bring things we learn back to our jobs, families and friends, thus making something concrete out of our seemingly self-serving endeavors. And lest we forgot, such things are sometimes just a raw celebration of youth and strength — sometimes, we just need to howl into the wind — or know someone else is.

Oh, and where does skiing fit in here? Plenty. We’d slog like dogs on our old style touring skis to reach those climbs. On Pyramid in particular, the approach was heinous. After sweating up nine miles of snow covered road with 60 pound packs, we’d ski and sometimes wade up through steep gnarled avalanche vegetation that gave way to snow choked avy chutes. We often use ropes on the approach and deproach to save ourselves from being swept 2,000 vertical feet down into the valley. That’s where I first learned to use ropes in avalanche terrain, something that’s saved mine and many other’s lives countless times.

Kennedy did go on to some amazing ascents in the great ranges (see my 1999 Kennedy profile). Me, I mostly stayed closer to home, eventually shifting to ski mountaineering.

Local Climbers Make First Winter Ascent on Pyramid

Aspen Times article — February 19, 1976 issue

by Andy Stone

The first winter ascent of the north face of Pyramid Peak — and possibly only the third ascent ever of the nearly 2,000′ vertical face — was made February 2, 1976, by a group of three Aspen climbers. The climbing group included Michael Kennedy, editor of Climbing magazine, Lou Dawson, of the Aspen Climbing School, and Michael Pokress.

The three forged a route up the right side of the face, which excited onto the west summit ridge about 600′ below the peak.

“It was a really hard winter climb,” said Kennedy, “One of the hardest ever done around here, I think. It was consistently difficult climbing, all the pitches were at least 5.7 and some were 5.9.”

These numbers represent a scale of relative climbing difficulty, on which 5.9 is very nearly the highest grade.

“Sometimes the holds were so small that we had to take our gloves off and climb bare-handed,” added Kennedy.

The route was divided into 10 sections or pitches, with the three men taking turns leading the pitches.

The first man up would do the actual technical climbing, with a second man anchoring his protection rope from below.

When the pitch was completed, the lead climbers would anchor the rope and the second man would follow up the rope using mechanical climbing aids called jumars.

The second man would then start up the next pitch, while the third climber jumared up the section below, removing the climbing hardware used for protection by the lead climber.

Leapfrogging past each other this way, the three were able to move rapidly up the wall.

Starting from their overnight camp in a large snow bowl at the base of the mountain, they were on the face by 7am and reached the summit just before sunset, 10 hours later, at about 5pm.

“The last pitch was really spectacular,’ said Kennedy, “It was a perfect chimney that ended in a notch leading onto the west ridge — Lou led that pitch — and when you got to the top and pulled yourself out onto the ridge, you were out onto the ridge, you were out into the sunshine for the first time on the entire climb. It was really beautiful.”

The descent, by the west ridge route used by most climbers, went much more quickly, taking just two hours, even though part of it was negotiated after dark.

The three were slowed somewhat on the trip down by the need to rope up again when crossing dangerous avalanche chutes.

The expedition was the second time that the three men have tried the climb this winter. An earlier attempt two weeks before was halted when bad weather caught up with the climbers when they were just 300′ up the wall.

During that attempt, high winds and blowing snow at that time engulfed the three in continuous spindrift avalanches, which don’t have the force to knock a climber off the wall, but which do keep him covered in a steady stream of powder snow.

“You can’t see, you can’t move, it’s impossible to climb at all,” said Kennedy, “At one point I just had to stand still on a ledge for over 10 minutes, getting covered with snow. “We were cold and wet and we had to go back down.”

The weather closed in even more firmly after that retread, with a “small” avalanche carrying Dawson nearly 300′ down the slopes at one point.

They returned to their tent to find it filled with snow and then, after clearing it out, they spent a miserable night huddled again the winds and had to dig their way out again in the morning. Kennedy said that they are planning still another assault on the face later in the winter, in hopes of climbing an even more difficult and direct route to the summit.

The route planned for the next climb goes straight up the middle of the face, ending with a 300′ vertical buttress just below the summit.

This last pitch has never been climbed, as both summer parties who have climbed the face (Harvey Carter et al) turned west and exited off the ridge just below the buttress.

“I think that part of the wall is just too dangerous to climb in the summer,” said Kennedy, “But I think it can be done in the winter.”

He explained that the rock there is dangerously rotten and crumbling, noting that climbers would be in danger not only of having the rock they were standing on break off, but also of being hit by large rocks falling from above.

In the winter, however, the rock is frozen together and should be more stable, Kennedy said.

He estimated that the direct route planned for the next attempt should take “at least two or three days” to climb, with climbers bivouacking at night on the face.

But that’s next time. . .and right now the three climbers are happy with the climb just completed.

“We worked hard to do it,” said Kennedy, “And it was really satisfying to make it. It was one of the few times in the winter when conditions were really good and the weather was with us.”

“It was a hard route, but it wasn’t one of those climbs when you think you might die if you make the slightest mistake.

“At the top of each pitch you’d stop and think ‘Hey, this is really fun.'”

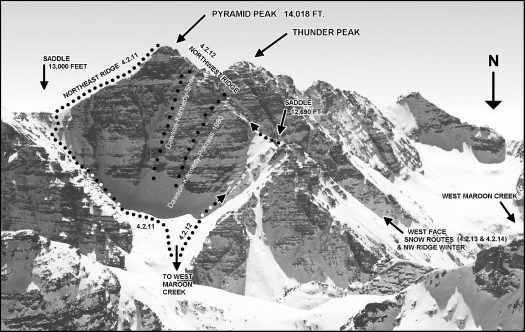

Pyramid Peak viewed from north, with our winter north face climbs marked. Just getting to this in early days without using snowmobiles was a difficult ski tour. Click to enlarge.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.