Alpine tour (AT) backcountry ski touring and mountaineering gear allows a free lifting heel for skiing uphill, but latches down for the descent so you can ski downhill with a binding like an alpine ski resort rig. It is frequently called randonnee gear, after the French word for “tour.” Other terms are “ski touring” and “skimo.”

Modern AT ski touring gear is terrific for going uphill on skis, and the “down” isn’t too shabby either.

Will AT gear make you ski like a god and climb like a Ruedi? Is it a future wave or past gasp?

“Silent revolution” is an apt way of describing the randonnee backcountry skiing scene over past decades.

In the 1950s and 1960s, when nordic ski gear was too frail and difficult for most downhill skiers, latched heel AT skiers earned their turns all over the world. Free heel nordic telemark gear improved, but telemark racing and resort skiing distracted many free heel skiers. Meanwhile, a quiet cadre of AT skiers continued to push the outer limits of ski mountaineering, ever mindful of the words: “backcountry skiing is not what style of gear you ski on, it’s not what kind of turn you make. Backcountry skiing is about what mountain you ski on — it is about using gear that works for your purpose, with the least compromise of safety and efficiency.”

Contemporary telemark gear is amazingly good, but is heavy and surprisingly complex, sometimes still prone to breakage, and most lacks any kind of reliable safety release (of great concern in avalanche terrain). More, when you climb with most telemark bindings, you fight the resistance of boot flex and binding springs. (Some telemark bindings allow you to release this resistance for climbing, proving that at least some in the telemark community believe this to be an issue. That being said, note that telemark bindings with this “touring pivot” still do not provide the range of motion of an AT binding, and are heavy).

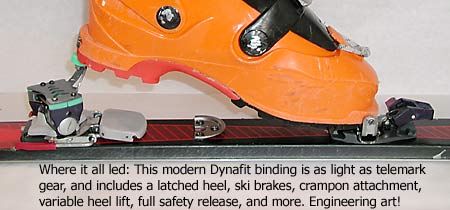

Meanwhile, AT ski touring gear has lost weight, by default allows a resistance free stride on the uphill, and has achieved an elegant state of design that includes safety release and other modern binding features. Randonee AT is thus an incredibly fun and efficient way to ride wild snow.

I’ve seen free-heel telemark skiers do amazing athletic feats. I’ve been out with split-board snowboarders who handle wilderness snow with elegance and skill — but after seeing it all, I’m certain that alpine ski touring AT gear is still the most fun, efficient, safest, and best tool for glisse alpinism backcountry skiing.

Intrigued — with an open mind? Read on, and bear in mind that I’m writing about gear for backcountry ski mountaineering, NOT RESORT SKIING!

While skiing and the control of skis downhill began in the Scandinavian regions (both with telemark and parallel techniques), skiing as we know it today began in the 1930s and 1940s, when “down mountain” skiers in the European Alps began to make tighter controlled turns on steeper terrain using what could be loosely termed Arlberg methods, today known as parallel.

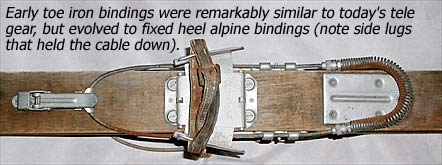

Gear of the day followed suit with beefy steel “toe irons” and stiff soled boots that bear an uncanny resemblance to today’s plastic telemark boots.

The short of all this was that equipment used for the early Arlberg methods allowed skiers to pull a telemark or cut a parallel turn: versatility similar to today’s top-end telemark gear.

So why did parallel become the method of choice? Those skis of yore were long, heavy, and hard to turn. In steeper terrain the parallel technique (no doubt with plenty of stemming, step turns, and more) simply worked better than the telemark. What’s more, the parallel turn proved to be faster for slalom racing . As a result, telemarking was relegated to novelty status and landing jumps in Nordic competition, and parallel technique became popular.

Sun Valley founding skier Florian Haemmerle, extreme vorlage circa 1938. (Ketchum Community Library)

In terms of gear evolution, the critical factor was that, while early skis allowed heel lift, parallel turns could be done with your heels on your skis. Evolving past that, skiers soon discovered fun, elegant, and powerful moves that required resistance to heel lift.

(My favorite of these older techniques, known as vorlage, involved exaggerated forward lean, with heels lifted off the skis and hanging against the resistance of tight “active” cable bindings.)

Vorlage depended on the same “heel retention” that modern “active” telemark bindings provide, and was really just a form of heel retention that could be used to lever skis just as an alpine skier does with his heels latched down (note the torque of the vorlage levering this man’s ski tails off the snow, and thus bending the skis into an arc, circa 1944).

As parallel technique and gear improved, skiers wanted more resistance to heel lift. An interesting development that resulted was the Amstutz Spring. This fascinating device, which would still work well today, was simply a strap you cinched around your instep, then attached to a spring or rubber band that was anchored to your ski behind your heel. Perfect. You could lift your heels with adjustable resistance-or cinch down for an almost modern alpine-like feel.

Later, as boots and skis improved, skiers eschewed free heels altogether and tied their cables down with catches mounted on the ski sidewalls.

But the cable was still the limiting factor — a system fraught with design problems (some which seem insurmountable even with present telemark cable binding technology). Thus, 1940s cable bindings, without need for heel lift, gave way in the 1950s to the first modern latched-heel bindings, which in turn evolved into today’s step-in alpine bindings.

These early developments marked the beginning of a long and sometimes strange trip for back country skiers — a journey we’re still on.

The beauty of the older cable bindings was their usefulness for both touring and downhill. But as bindings evolved, newer latch-in bindings such as the Miller and Cubco (the precursors to step-ins) eliminated the touring option. Backcountry skiers, especially European glisse alpinists, wanted the benefits of this latest alpine gear, only with the option of lifting their heel for hiking.

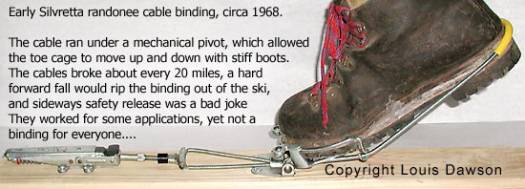

The solution was simple, at least in concept: use alpine type heel and toe units with added gizmos to allow heel lift for the uphills. In execution this was an engineering nightmare. Some of the first AT bindings, such as the original Silvretta pictured above, tried to mate a mechanical toe pivot with a cable. The result: kludgy bindings with no lateral toe release; broken cables; ripped screws, skis that were not interchangeable between right and left feet, etcetera (sound like telemark gear?).

Other early AT bindings used a mechanical linkage lift at the heel. The Marker TR “wishbone” was the best known of those torture devices, which were known to result in heel tendonitis and abnormal hip motion (at least for the male of the species).

The most effective AT design of the 1970s and 1980s was the “plate” or “frame” binding. This type of rig incorporated toe and heel units on a rigid platform, in turn attached to the ski via a front pivot and rear latch. The biggest problem with early plate designs was weight. Not only did you haul the heavy release machinery of the day, but the plate, hinges and latch added more pounds. One of the early modern plate bindings was made by Eiser, and became available in North America around 1976. The Eiser was a hefty rig with a thick plastic plate connecting a basic alpine-like release toe and Marker heel, along with a catch and pivot system to latch the plate down for skiing, and release it for touring. Tyrolia made a similar binding, as did other companies.

European glisse alpinists, often strong lifelong skiers accessing terrain from trams and lifts, were comfortable with heavy plate bindings. Millions of European AT skiers voted with their feet. They voted that their gear was fun, efficient, and the best way to practice ski alpinism. But most American backcountry skiers of the late 1960’s and early 1970s did not have much mechanical access to natural snow, and coming from climbing and Nordic ski backgrounds they often lacked the alpine ski skills needed to realize the full potential of European AT bindings. What’s more, as a rule they didn’t tackle terrain as steep as their counterparts in Europe. As a result, American backcountry skiers of those early days did not demand as much from their gear, so the AT tradeoff between downhill performance and weight was often unnecessary. Result: increased popularity of ski mountaineering on free-heel nordic gear (now known as “telemarking,” even though free-heel equipment can be, and often is, skied with parallel alpine technique).

(But things change — oh how they change. Though early free-heelers of the 1970s extolled the manly virtues of skiing on minimalist gear and “playing by different rules,” and “having more fun than anyone else,” telemark gear has now become a de-tuned version of AT gear, leaving toothpick skis and meager boots as distant, sometimes fond memories. Now, with huge plastic “telemark” boots locked to modern fat skis by compression springs that could suspend the space shuttle and cables that could tow a monster truck, you have nothing less than an AT setup. For proof, witness the number of free-heel skiers who make parallel turns.)

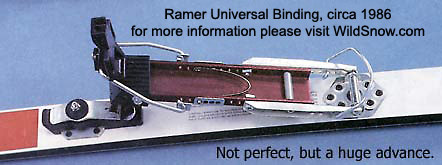

If clunky AT gear was one of the forces behind the early days of the telemark renaissance in America, it also provided impetus for its own evolution. The late Paul Ramer, an admitted equipment junky, mad scientist inventor and baby boomer, wanted better. Throughout the 1970s and in to the ’80s he refined his Ramer plate binding. His concepts were revolutionary. Ramer eliminated a huge amount of weight by combining the release mechanism with the toe pivot. And being less inclined to suffer than European traditionalists, he invented the heel elevator for climbing (now incorporated in all AT bindings and also sold for tele rigs). Despite a legacy of problems with the binding, it achieved a diverse popularity.

Ramer Universal, circa 1986. Ramer bindings revolutionized the ski touring binding market with one of the first heel lift system as well as a ball-socket joint at toe that eventually led to modern tech bindings.

Europeans noticed Ramer’s ideas. Then, as they typically do with much American innovation, the Euros gradually refined the concept of lighter and easier to use AT systems. For a time it was nip-and-tuck, as the Ramer remained the lightest full-function binding. Yet many skiers were never comfortable with the Ramer safety release (I have personal experience with that, having spiraled my left tibia on early model Ramers in 1976). More, operating the binding was somewhat complex (it required frequent adjustments and messy greasing), it just plain looked weird — and hey, it could have even been lighter.

I brought up all those points with Paul Ramer during a conversation in the mid 1980s. While Paul was a fine man, he was not known for acting on feedback. I mentioned that the binding could be engineered to look better, weigh less, the release could be improved, and they had too much of an erector set appearance. He just smiled and said “they’re light enough.”

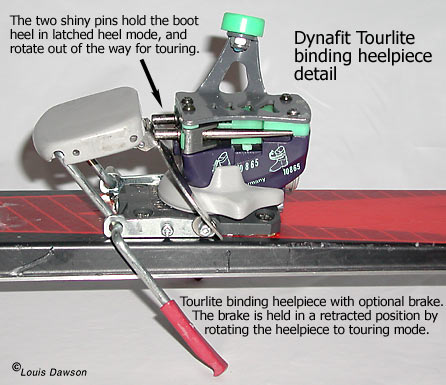

Ramer was wrong. In the late 1980s, Dynafit (the European boot maker known for its lightweight Tourlite boots) refined development of the Tourlite binding. Working on the principle of using the boot to connect heel and toe pieces, Dynafit built small fittings into the boot sole, designed ski fittings with uncanny simplicity, and flip-flopped the whole backcountry binding picture. When the Tourlite binding was released in Europe some years ago (in the U.S. in 1994), fixed-heel skiers finally had a system that was lighter or the same weight as beefy telemark gear, toured with miraculous ease, and skied superbly. The binding sold like crazy in Europe (the inventor reported to me in 2002 that they sell an average of 13,000 pairs a year), but was not widely distributed in the U.S. and had only limited availability in Canada. Nonetheless, those of us who wanted them were able to get them. They worked as well or better then the Ramer, and were about half the weight. Click here for extensive Dynafit binding information.

Early Dynafit TLT tech binding heel circa 1994 led to current variety of tech bindings.

Modern ‘tech’ binding system, Dynafit TLT.

The next binding to go on a diet was the since discontinued Silvretta SL, which again used the concept of dedicated fittings connecting the binding via the boot sole. The SL weighed just a bit more than the Tourlite, but had no release in touring mode. With no release, if you took a forward fall and stressed the binding without your heels latched down, it would literally explode and eject parts all over the mountain side. Blah.

Fritschi, a Swiss company, was the next to successfully play the weight game. They stuck with the plate binding concept, but used modern materials and engineering to build the enticing Diamir binding, which weighs about half of what most plate bindings have weighed over the years (it weighs about the same as the Ramer, but is much more functional). What’s more, the Diamir has a heel and toe with conventional alpine look and feel, thus appealing to skiers who saw (often mistakenly) the Tourlite and Ramer as contraptions that might have been better suited for trapping small vermin than to outdoor sports.

Presently, the Diamir and Tourlite rule the AT binding roost — and they deserve their perch. These elegant engineering statements combine versatility, light-weight and ease of use in ways that binding makers of even two decades ago would have considered an opium dream.

So, if you can get tele gear that’s virtually randonnee AT gear, why latch your heels? If you’re an experienced skier-if you’ve felt the essence of glisse-you know there is something special about skis firmly attached to your feet. In an almost supernatural way, your boards become extensions of toe and heel. You get amazing quickness, precision and response with a fixed heel — watch a World Cup slalom race for illustration, and observe the majority of radical ski photography. Also observe the type of gear used by the top ski alpinists of the world.

Skiing the force and control of locked heels is pure unadulterated FUN. It’s an incredible ride that having your ski tails flapping in the wind only gets in the way of. Indeed, it’s not uncommon to hear performance tele skiers talking about “heel retention,” or how their cable bindings keep their skis firmly snugged up to their heels — watch out boys, next thing you know you’ll be latching ’em down! You’ll also hear telemark evangelists endlessly blather about how much more fun or “spritual” their sport is than other forms of skiing. Doggerel. Again: Cutting precision turns with a fixed heel, blasting through crud and powder, handling a steep couloir with skill and verve — fun is a word that doesn’t even come close to this wonderful experience.

1960s Silvretta binding toe detail.

What is more, it is easier to transfer force to a ski when your heel is fixed. Thus, AT gear can be built with less beef and weight than equivalent telemark free-heel skis and bindings — an engineering truth that’s caught many of us by pleasant surprise. This is obviously true of bindings, but randonnee racers are proving that AT bindings allow the used of incredibly short and lightweight skis for fairly tough descents — try telemarking difficult terrain on a pair of the 150 or 160cm skis super-light AT skiers and rando racers use — it simply won’t work unless you fake your telemarks, or revert to parallel turns. More, because most telemark bindings don’t have safety release, tele skiers who fall run the risk of ripping their bindings off their skis. The solution to this has been to add more and longer screws, as well as build skis with a heavy reinforcement in the binding mount area. Thus, ever more weight and less safety.

Also consider overall system reliability. Today’s randonee bindings are durable (aside from rare manufacturing defects in first-year products), and with safety release they are much less prone to being broken during hard falls. Thus, as telemark bindings become heavier to avoid breakage and provide a solid (and dangerous without safety release) boot/ski connection, AT bindings have become minimalist art.

(The above is an amusing irony, as the original telemark evangelists touted the simplicity and light weight of their gear as being one of their prime reasons for using it. They claimed their gear was more “fun.” You want fun? Try flying up the hill on a pair of lightweight AT skis with 13 ounce Dynafit bindings, then latching your heels down and making firm aggressive turns through everything the mountain can throw at you. Now that is FUN!)

Yes, if downhill performance is not convincing enough, take a look at the uphill. A free hinging AT pivot is more efficient than bending the stiff plastic baffles of a telemark boot, and pulling every step against the cable and gigantic compression springs of a telemark binding. And if you are mountaineering, the AT boot is clearly superior to the ludicrous performance of duckbill telemark boots for rock and ice climbing. (Note: some telemark bindings are now available with a touring setting that allows a free hinging pivot similar to that of rando bindings. A good thing, and proof this is a valid issue, despite past televangelists frequently arguing to the contrary.)

Indeed yes, for a host of reasons, fixed heel AT gear is a terrific way to go.

But don’t get me wrong. I think what’s happened with telemark gear is fascinating (in my view, it has become a version of AT gear, albeit less durable, heavier, more dangerous in avalanche terrain, and less efficient), and I respect the athleticism and spirit of the tele turn practitioners. More, telemarking allows skiers to look different than the mass of fixed heel skiers at ski resorts, thus allowing telemarkers to have a visible identity, and thus fulfilling a basic need many humans have and making telemarking “hip.”

I’ve telemarked, and enjoyed it. In fact, I was one of the early 1970’s skiers in the Aspen and Crested Butte area who experimented with forcing nordic gear to work for ski mountaineering. While I evolved to using AT backcountry gear for ski mountaineering, I learned that for tours with much flat terrain, mid-weight telemark gear is terrific. Then there is snowboarding — with a split board or showshoes for the uphill it’s a fine option. And along with all that, AT gear has been engineered to levels no one could imagine. Thus, my take: If you are already an experienced alpine skier looking for backcountry ski touring devices, choose AT gear first and master it. Then, if you then go on to tele or board in the backcountry, you’ll know what you are missing.

3 comments

“Free the heel, free the mind”

2023 Bucketlist: Hike into Eagle Wind via Berthoud Pass and ski trees all day for free

I’ve only been tele’ing (just tele) since the mid 90s, but I am finally done with telemark – my knees just can’t take it anymore. Chondromalacia patella

sucks the joy right out of bending the knees. Plus my old Garmonts just blew out a bellows. Doing parallel turns on tele bindings isn’t hard but

difficult snow sure can throw one off even with the best balance. For me, there really isn’t any point in buying a new set of tele boots.

I was always told randonnee is French for “can’t telemark” and in my case, that ain’t far from the truth. Time to buy some new gear.

But now what am I gonna do with my Line Assassins mounted with Linken bindings? The G3s, the super loops…

You’re right, Lou. I’m a slow learner, but I came around to agree with your points in favor of modern AT gear a half dozen years ago. This change has extended my potential skiing in the backcountry by years. After three decades of making telemark turns, and enjoying them a lot, I have to admit skiing on AT gear is at least as fun. I go faster and turn quicker when I need to.

.

For those enchanted with the telemark turn, I say, sure! It’s harder to learn, and works you harder too, both uphill and down, but it’s different and gratifying. I’m a better skier for having skied ridiculous descents on ridiculous equipment. But no more.