Skadi opened up, lid is upside down at bottom of photo. Transmit for a week, receive for a month -- a bit different than these days. Showing charger plug, earphone, etc., penny for scale. The unit is about 7 3/4 inches long, serial number 4252 is hand engraved on the inside plastic. It was originally owned by an Aspen Mountain ski patrolman. 14.5 ounces, 412 grams. Was usually carried with the lid duct taped or rubber banded, in a large coat pocket or fanny pack. Click images to enlarge.

The first effective electronic avalanche rescue beacon (radio transceiver), called the Skadi, was created in 1968 by a research team headed by John Lawton at Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory in Buffalo, New York. Before then, at least one American, an Englishman and various Europeans had developed electromagnetic methods to locate avalanche victims, but their experiments and products lacked enough range and accuracy for the fast location needed to save lives.

Skadi had a long lasting battery and approximately 90 foot range — it could truly save your hide. The first production units were sold in the early 1970s (most likely 1971), and the Skadi quickly became a standard item for workers at risk of snow avalanche burial, such as ski patrollers.

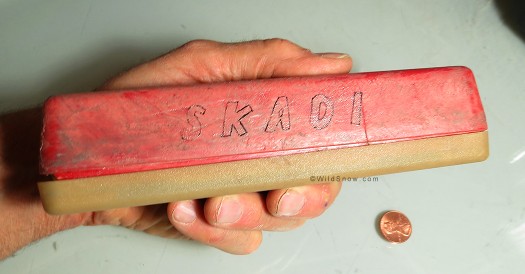

Skadi unit was known as the 'Hot Dog' for obvious reasons. The lettering was originally a sold yellow gold color. This lettering was penned in after original was worn off and otherwise obscured by hardened duct tape adhesive that was chemically removed.

As with many modern inventions, Lawton’s device was a culmination of ideas and experimentation involving many people. In particular, well known avalanche expert Ed Lachapelle (1926-2007) had an influence. In the late 1960s LaChapelle was working at Alta, Utah and involved in the development of modern avalanche safety ideas and techniques, including methods of finding buried avalanche victims. In his words:

“I was experimenting with a search technique for avalanche victims and had built a small, pocket-size radio transceiver working at upper end of broadcast band. The idea was to pick it up with a portable radio receiver, using the receiver’s loopstick antenna for some directivity. John Lawton happened to be skiing at Alta and saw me doing the experiments. John said “I think there is a better way to do this.” He went home and assembled an experimental pair of units using an audio frequency induction field and sent them to me to test. They consisted of a pocket transmitter about the size of a cigarette package and a plug-in antenna in the form of a wire coil about a foot in diameter to be sewn into the back of a parka. They worked! In fact the large coil antenna gave more range than the ultimate marketed Skadi, but obviously was awkward to use and limited the user to the chosen parka.”

Lawton downsized the unit, mostly by eliminating the parka antenna and replacing it with a smaller antenna that could be built into a handheld plastic box. Just as today’s avalanche beacons function, the original Skadi radiated a magnetic field by pulsing electricity through a copper coil, with reception done by picking up the magnetic field and producing sound in a small earphone.

Volume control. Finding a victim was done excusively by bracketing based on volume level; you'd turn down the level so you could more easily discern changes in level as you searched. The concept of 100% audio searching, with an earphone, had advantages such as simplicity. But an external corded earphone was most certainly a fiddly component.

The original production unit was enclosed by an elongated plastic box, about 7 3/4″ long x 1 3/4″ high x 1 1/4″ wide. Due to the red color of the box, and its curved corners, users (most often ski patrollers) nicknamed it the “hot dog,” or “hot dog Skadi.” The first production units were sold in the early 1970s (most likely 1971), and the Skadi quickly became a standard item for workers at risk of snow avalanche burial.

One can only assume that the Cornell team put much time and effort into the method of finding a buried unit by receiving the transmitted signal (as building a transmitter is a simple exercise.) Their elegant and simple method, which found its way into virtually all later beepers, was to give the user an audio signal and a volume control — nothing more. For the radio/audio signal they chose a frequency of 2.275 kHz, which is audible to the human ear. By doing this, they eliminated much of the expense and complexity of a radio transceiver that has to convert a non-audible signal to a tone you can hear. What’s more, while higher frequencies such as the current standard of 457 kHz have advantages, the frequency Lawton chose was virtually free of interference, and worked well when blocked by objects such as rocks and trees. (Due to various political issues, and greater range, the higher frequency became the international standard in 1996.)

The signal was louder when units were closer together, so by using a grid search pattern a searcher could home in on a buried victim by listening for volume changes.

As the human ear is more sensitive to such changes at lower levels, the volume control was constantly turned down as the signal got louder, thus allowing precise location of the source.

In the field, provided the operator got lots of practice, the early Skadis worked surprisingly well, though the fact remains that about 50% of avalanche victims die because of trauma rather than suffocation, thus rendering the device useful only with half of burial victims.

Skadi selector switch and Nicad D-cell battery. The units were obviously hand built, mostly off-the-shelf electronics parts.

Per its use as an institutional tool, the original Skadi had a built-in rechargeable NiCad C-cell and charging circuit. Transmit was rated as 1 week, receive as 1 month. In practice, Skadis were often left plugged in every night. A small toggle selector switch near the battery changed modes between charge/off, receive, and transmit.

The Skadi worked. It saved lives and was soon copied and improved by European manufacturers, who changed to a more elegant form-factor built around replaceable AA batteries rather than built-in rechargeables. Today’s amazingly featured digital avalanche beacons incorporate microprocessors to simplify searching, and have more features, but all work on similar principles to the original Skadi. Hats off to John Lawton and his team.

Notes

The word Skadi comes from the old Norse word Skaði, variant Skade. This female is often referred to as the goddess of skis, she traveled on skis, carried a bow, and hunted. She was the daughter of the giant Thiazi, and married Ullr, the god of skis.

Early attempts to make avalanche victim locator devices included the SKILOK, invented in England, with a range of about 25 feet.

Date of invention: The 1968 date for Lawton’s invention is the common wisdom, but needs to be verified. It refers to the date the Cornell team “invented” the SKADI, not to the date it was first sold to the public. Northwest ski historian Lowell Skoog graciously provided me with a page copy from Summit Magazine, March 1971, which displays an announcement for “Avalanche Search Device — A lightweight transmitter-receiver small enough to carry in your pocket has been developed as a safety device for those traveling in avalanche terrain…units are called “Skadi” and are available from Lawtronics…Buffalo, N.Y.”

This label was pasted over the address under the cover when the corporation changed its contact information. The logo is classic and speaks backcountry skiing.

Who invented it? As with many inventions, various individuals may have been considering similar concepts to the Skadi when it was being invented. In particular, Lowell Skoog told me that avalanche expert Ed LaChapelle may have been considering a similar device during his days in Alta in the 1960s. I subsequently contacted LaChapelle, who provided me with the information about his involvement (see text of LaChapelle letter below).

NiCad battery memory effect: If not completely drained before charging, early NiCad batteries would sometimes not take a maximum charge. If such batteries were used day after day, and charged every day without completely discharging, this effect could result in a nearly ineffective battery with virtually unknown capacity. Nonetheless, according to LaChapelle, the NiCad was chosen for its better performance while cold compared to alkaline batteries.

Relevant text from Ed LaChapelle letters:

“Dear Lou, Here’s the Skadi history in brief. I can’t remember the year, perhaps your research will turn it up. I was experimenting with a search technique for avalanche victims and had built a small, pocket-size radio transmitter working at upper end of broadcast band. The idea was to pick it up with a portable radio receiver, using the receiver’s loopstick antenna for some directivity. John Lawton happened to be skiing at Alta and saw me doing the experiments. John said “I think there is a better way to do this.”. He went home and assembled an experimental pair of units using an audio frequency induction field and sent them to me to test. They consisted of a pocket transmitter about the size of a cigarette package and a plug-in antenna in the form of a wire coil about a foot in diameter to be sewn into the back of a parka. They worked! In fact the large coil antenna gave more range than the ultimate marketed Skadi, but obviously was awkward to use and limited the user to the chosen parka. With this start, John came up with the initial “hot dog” Skadi, using a ferrite loopstick inside the unit. To get an effective antenna he used a long loopstick, hence the elongated shape which gave the unit a hot dog appearance. The final, more blocky shape used a shorter loopstick with more efficient electronics.”

“The choice of an audio frequency induction field was a good one. The Skadi was practically impervious to outside interference and could locate buried units under rock or dirt as well as snow. The higher frequency units, mainly originated in Switzerland, had advantages of lower power consumption and improved search performance. This led to the dual frequency units and eventually to a radio frequency (just below the broadcast band) as the international standard.

“A technical clarification: the Skadi in transmit mode generated an audio frequency induction field at 2275 Hz (that’s where the crystal control comes in), not just a broadband pulsed copper coil. Such a field falls off with the cube of the distance from the transmitter, which makes it more sensitive for searching in contrast to a radio frequency transmission which falls off with the square of the distance from the transmitter. (I got this explanation from John.)”

“Best regards, Ed LaChapelle”

In 2013 Skadi inventor John Lawton contacted this writer, a few excerpts from correspondence with John:

I conceived and developed SKADI while employed as an electrical engineer/pilot by Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, CAL, in Buffalo, NY. At that time I was also a volunteer ski patroller at the Glenwood Acres Ski Area, now a part of the Kissing Bridge Ski Area, located approx. 30 mile south of Buffalo in Colden NY. To the best of my knowledge there never was a snow avalanche at Glenwood Acres. (There may have been people avalanches). Nevertheless we practiced avalanche rescue in the sand dunes on the Canadian side of Lake Erie. We used electrical conduit for probe poles. It was suggested that the number of false alarms, due to the probe hitting an object other than a buried body, could be reduced by cutting teeth into the ends of the probes and turning the probe to see what the teeth would bring up, e.g. wood bark, threads, blood etc.

I said to myself there has to be a better way and that led to the development of SKADI. I discussed the issue with Ditmar Bock, one of my coworkers at CAL and we conceived SKADI and CAL patented it. (In accordance with our employment contracts we were both listed as the inventors but the commercial rights of the patent belonged to CAL.) I formed a company, called it Lawtronics, Inc and started to make SKADIs in the basement of my home and testing them locally and also in CO and UT. I met Ed LaChapelle, Monty Atwater, Bings Sandal and Ron Perla at Alta and remember talking with them about the SKADIs.

At that time almost all of CAL’s work was sponsored by the defense department but there was interest in development of commercial products. It was suggested that SKADIs could be used to locate firefighters who became disabled at a fire. CAL bought a few of the SKADIs which I had built in my basement and also assisted me in demonstrating them at various ski areas. The Swiss army got interested in SKADIs and bought several SKADIs from Lawtronics.

The town of Lockport, NY is located on top of the Niagara Falls escarpment. There are numerous caves under the Lockport and these caves are part of the town’s sewer system. At that time the town was interested in mapping these caves and had used spelunkers to explore and survey the caves. This proved to be a difficult job and I suggested that if they gave a SKADI to one of the spelunkers I could trace his path above ground. This idea turned out to be very practical and in an hour or so we traced out what they had been working on for months.

There was an international competition at the SLF, Institut fuer Schnee and Lawinen Forschung (Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research) of the ETH, Eidgenossiche Technische Hochschule (Federal Technical University) at the Weissfluhjoch near Davos Switzerland of technical means for avalanche rescue. I vaguely remember that there was a British system called Ski Lock, a Yugoslav system called Lawinenspecht (Avalanche woodpecker) and SKADI. Anyway, SKADI turned in the best performance.

The first save by means of SKADI and as far as I know, by any avalanche rescue beacon, occurred on Jan. 10, 1972 at 11:00 A.M. At CMH (Canadian Mountain Holidays) the victim was Roy Fisher.

John Lawton

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.