Plum backcountry skiing binding lineup. J'Envoie du Gros aka Phat Boy at top, Plum Guide, then the diminutive Race model. Click all images to enlarge.

Do tech bindings break? Ask people who ski the now myriad brands, you’ll hear mostly good reports mixed with a few slasher stories. Unique to tech bindings? Nope, any ski binding can malfunction or break, and I’ve never seen anything definitive that makes me think the tech form-factor is any less durable. Indeed, the opposite is frequently true. Proof: in my travels I see more decades old tech bindings in play than all other geriatric AT bindings combined.

The classic tech ski binding design, now more than a quarter century old (!) is still going strong, with hundreds of thousands of the tiny grabbers in play around the world. And yes, now that the fundamentals of the tech binding are mostly out of patent, newcomers to the genre seek to make evolutionary improvements. Enter the one with that flirty name only some French guys could have come up with: Plum.

(For more Plum technical details, please see our comparo post.)

Plum began producing full function tech bindings in 2007, with focus on skimo racing. A few years later they delved into the touring and ski mountaineering market. Present offerings are diverse; eight (depending on how you count) models ranging from the super lightweight Race to the freeride wide-base Yak and J’Envoie du Gros. Rental bindings and a unit for lightweight skiers round out the portfolio. Guide model is the sweet spot by WildSnow.com standards and popular worldwide.

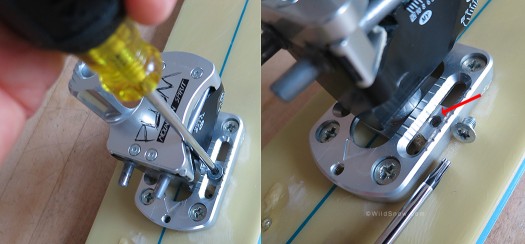

Plum length adjustment is the only inherent weak point in this design. A narrow shaft star 20 driver is ideal, and the bindings come with a small right-angle star driver as well that can reach the fasteners without the need to rotate the binding out of the way. The screw heads strip easily.

Plum Torx-20 star drive tool. It's too easy to torque this at an angle and bung the star socket in the screw head.

After mounting, adjusting and using Plums all winter, one Achilles heel stands out. Rather than the threaded spindle for/aft boot length adjustment common to most other tech bindings, you adjust Plum by moving the heel unit for/aft on a track, then affix with short machine screws. Two problems: First, the star drive screw heads strip out easily — observe on demo bindings where you’ll see this as a somewhat common problem. Second, the machine screws rotate into a thin aluminum plate and the threads easily strip. In the first occurrence, so long as you can get the screw out you can easily replace with a new one (spares recommended for shop and repair kit.) The second concern is more troublesome. Strip the base plate threads and you’re looking at a complete tear down of the binding and swapping a fundamental part that’s doubtless expensive.

To be fair, Plum’s method of length adjustment has an upside. Unlike other tech bindings that use the ski top surface as support for the binding spindle base, the Plum backcountry skiing binding locks everything together and the larger base thus gives max support. Bindings that rest the spindle on the ski top can eventually wallow a depression in the ski material, thus introducing play and damaging your skis. On some of the geriatric setups I’ve repaired, I’ve seen the spindle base eat so far into the ski it went almost to the core. But that’s after an unusual decades long use cycle (as in, “I love my 65 mm wide 210 cm long skis; why should I change?”).

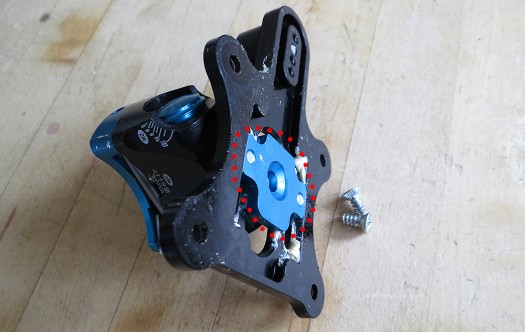

Plum heel unit, spindle base (indicated by red circle) is integrated into the main base plate via attachment with machine screws. With other brands, the spindle base rests directly on the ski top surface and uses the ski as support without integration with the remainder of the base plate. In heavy use this results in inevitable damage to the ski topskin and added play as the spindle base wallows out a pocket it sits in.

Many users attest that the overall appearance of the Plum models inspire confidence. Some even say they sound better. Next thing you know, we’ll be hearing about how well they kiss. How much of that is a value bias (pay more for something, it’s of course the best) or due to the beautiful monoblock machining is an open question. For example, though it appears to be black anodized aluminum the heel unit housing is actually plastic. Thus, a common misperception is that the binding is “all metal,” or “all aluminum.” Kudos to the mind control of industrial design.

Plum machine work is indeed impressive but the only significant strength improvements over other tech bindings are the heel lifter and the heel unit internal spindle (and perhaps the type of screws used to attach the heel top plate). Other than those items, any other perceived strength enhancements are psychological and like any other ski binding out there, Plums have been known to break.

Another thing about how Plums look. No problem with good looking design that doesn’t add weight for backcountry skiing. Compliments to Plum for making these sexy things without one tiny bit of faux material. We didn’t need to cut or grind anything off!

Form and perhaps function are also enhanced by the Yak and J’Envoie du Gros (Phat Boy) model’s wider base plates. Most certainly, it’ll be nice when all bindings are better matched to wider skis. If for no other reason than it looks odd having that wee thing on a 110mm platform. On the other hand, since the boot in a tech binding still attaches at the same exact width fasteners it ever did, thinking of a wider binding base as a blue-pill performance enhancer is suspect. In other words, make the tech 2.0 wider boot and binding, then I’ll listen. Oh, and the wider base of the Yak and Phat raises you off the ski 5 mm, thus exaggerating any play or movement in the system, and perhaps obviating any improvement in control.

Up to you. Ski a wider binding and see if you ski better. Doubtful. Oh, and are wider binding bases less likely to rip screws out of skis like a drunk frontier dentist pulling molars? Perhaps yes in some cases, but not to the extent where we need to go raising all ski bindings up a half centimeter so we can have our wider base plates.

Ultimately, have you ever ripped a properly mounted tech binding out of a ski? If not, don’t start crying in advance. Just make sure all your bindings are craftsman mounted.

And who knew? ISO 8364:2007 defines the reinforced binding mounting area on skis. Apparently the wider pattern of the J’Envoie du Gros and Yak bindings falls outside this, thus adding more mystery to if the wider binding base would actually make your binding screws hold better. Adding confusion, while ISO 8364 does define the _minimum_ width for binding reinforcement area, some brands do cover the whole binding area (from left to right) with the reinforcement, and for skis with metal layer this could be a non-issue. Only problem with that is knowing for sure the size of the hidden reinforcement area.

Tech bindings are not exactly the most ISO compliant consumer product out there and it’s been fun to watch an industry ignore mandated standards that stifle innovation. But it’s putting the cart before the horse to make a wider binding that may locate your binding screws outside the standard reinforced area. Style and appearance can be everything, however, and how your skis look on the Téléphérique du Midi could indeed make or break a fine day in Cham’.

No ski brakes available for Plum. Many (even most) core ski tourers around the world appear to have little interest in ski brakes, so this hasn’t been an issue yodeled from the mountain tops. On the other hand, using leashes instead of brakes is neanderthal in some situations — it’d be nice if Plum actually had a functional ski brake option. It’s said Plum is blocked from developing decent ski brakes by a slew of existing patents. Aftermarket, where are you?

Optional stomp block pad has proven value for aggressive skiers, but introduces uncontrolled friction into lateral safety release and also raises heel up in lowest heel-height touring mode, a concern for flatter terrain. Easy to remove-replace.

Uphill, we find no significant difference between the way Plum performs as compared to any other properly functioning and adjusted tech binding. Some users might prefer rotating the heel unit to adjust heel lift as compared to other brands with flip-up lifters. Also note, if you use the stomp block it makes for a less “heel flat on ski” flatland touring angle. For skiers who do a lot of low angled slogging that could be a factor. Otherwise, non-issue.

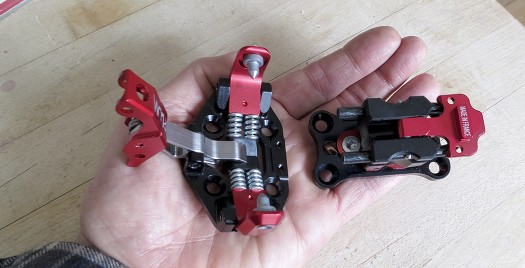

Lastly, check out the diminutive Plum Race model. Release doesn't adjust so we didn't test. We're also a bit leery of race bindings for long term abuse, since they put a premium on less material rather than long life. Plum version locks automatically when you step in. Popular in Europe, where almost everyone skis with their tech bindings locked, uphill and down. 6.5 ounces 184 grams with screws. Heel rotates for flat-on-ski walking mode.

Weights (one binding with screws, the gram numbers are direct from scale):

J’Envoie du Gros total 18.3 oz 520 gr (widest footprint, Yak model is also wider than normal)

J’Envoie du Gros heel 11.2 oz 318 gr

J’Envoie du Gros toe 7.2 oz 202 gr

Guide total 12.6 oz 358 gr (without 1.4 ounce 40 gram stomp block option)

Guide heel 8.4 oz 238 gr

Guide toe 4.2 oz 120 gr

Race total 6.5 oz 184 gr (without tiny crampon mount option, which weighs 6 grams)

Race heel 3.2 oz 89 gr

Race toe 3.3 oz 95 gr

Longest duration of test kiss: 2.32648 minutes, 70 dB.

Check out all our Plum ski binding posts.

Information on shopping for Plum in North America

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.