This Lou Dawson classic first ran on WildSnow in 2014. And as Lou notes, portions of the story appeared first in Couloir Magazine Volume VIII-3, February/March 1996 and his ski mountaineering history book WildSnow. Flat out, it’s with 100% respect and humility that we’re republishing Lou’s history of Bill Briggs.

(Lou is also working on a memoir titled Avalanche Dreams, you can find out more here.)

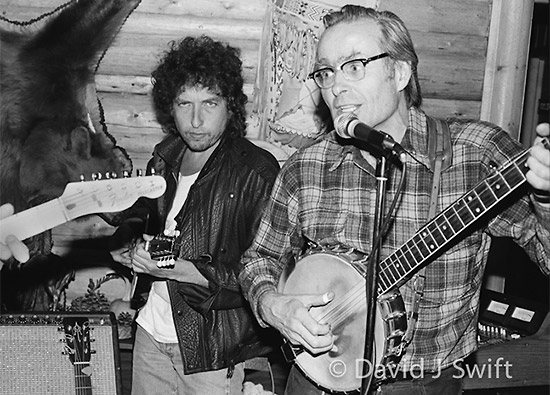

Here at WildSnow, we think it’s sound advice to find an adventure for yourself. Adventures benefit the soul and mental health and allow us, under the best circumstances, to unplug. Briggs’ adventures are legendary: First to ski the Grand Teton and part of the team forging the uber-classic Bugs to Rodgers Traverse. And as you might learn while reading this piece, he once jammed with Bob Dylan. Learn to play an instrument; that’s an adventure too.

Part of the history below also discusses depression and suicide. Just typing those words is heavy. And real. Resources to help are out there. If you need immediate help, you can dial 988 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

What you’ll find below are Lou’s words from 2014. Thanks for reading WildSnow and being part of this community.

Thanks to all who have contributed, those who understand and support our efforts at recording ski history, especially Roberts French, who kindly gave us permission to publish any of his photos from the Bugaboos traverse, and David Swift, who caught the photo of Briggs and Dylan and graciously allowed us to publish it.

William Morse Briggs gulped from his water bottle, laced his boots, and clicked his ski bindings. Standing at the apex of Wyoming’s precipitous 13,770-foot Grand Teton, he caught his breath and took in the view. To his east, the Gros Ventre mountains rose from the haze like a Tolkien fantasy, while the plains of Idaho faded two hundred miles west. Below his feet, snow like a steeple roof dropped thousands of feet to the chasm. Briggs’ plan was to slice turns on that snow — to be the first to ski down Grand Teton. On June 15, 1971, as his skis carved arcs down to Garnet Canyon, his goal became reality.

Who started North American “steep” extreme skiing? In truth, the sport has no single inventor hero; rather, it gradually evolved from steeper ski mountaineering that began, for example, in France in 1939 with French mountaineer Andre Tournier’s ski of Aiguille d’Argentière.

Despite such earlier foundational events, 1971 stands as a birthday in North America’s history of the sport. That year, Sylvain Saudan skied down Oregon’s steamy Mount Hood, Fritz Stammberger made his epic drop down Colorado’s defiant North Maroon Peak — and Bill Briggs skied from the summit of Wyoming’s cliff studded Grand Teton.

Out of all that, because of the Grand Teton’s stunning appearance and Briggs’ incredible and rich life as a ski mountaineer, his descent of the Grand stands as the seminal event in North America’s history of steep skiing.

By 1970s standards, the Grand Teton looked absurd to ski and still appears more suited to ropes and crampons than skis. The rocky spire is mostly cliffs, with choppy couloirs and a few measly patches of snow. Indeed, while backcountry skiing the Grand has evolved (as sports do) from “impossible” to possible, the descent is still considered a major accomplishment, though modern gear and technique have made it much more reasonable.

Briggs’s ski of the Grand was not only an athletic feat but also a triumph of spirit. Not only did he ski the impossible, but he did it with a severe disability.

Indeed, if skiing can be so much more than turns — if skiing can be life — Bill Briggs proves it.

Early Years

William Morse Briggs was born December 21, 1931, in Augusta, Maine. Briggs entered the world without a hip joint, and at two-years-old surgeons chiseled out a socket in his pelvic bone. Hinting at his deep and unorthodox spirituality (he practices the controversial religious philosophy of Scientology), Briggs recalls, “It was during the hip operation that I took this body. Whoever was there before me was pretty bright; he already knew the alphabet, and he could count — so I took the body and suddenly I couldn’t do the numbers or abc’s. Since I was expected to already do those things,” he continues with laughter, “I had to learn quickly.”

Briggs’ sister and older brother introduced him to skiing, but he soon went solo. At seven and eight years of age, Briggs spent countless days as his own ski instructor, picking a slope near his house and strapping on his father’s skis, which were twice as long as he was tall. Through grammar school Briggs continued to ski with no formal instruction, even gleaning technique from a skier’s board game.

Briggs had a hard time in high school. He was kept from sports because of his hip, while battling bouts of depression and never fitting in.

Exeter Academy

Prep school at Philips Exeter Academy was an entirely different experience. Straight away, the school decided to ignore Briggs’ disability, and he was required to participate in sports (as were all Exeter students). He chose cross-country running and, to his surprise, received a Junior Varsity letter.

At Exeter, Briggs met famed teacher Bob Bates, who became his most influential mentor. Bates was a devoted mountaineer — a member of the American Alpine Club and a K2 expedition survivor. Moreover, Bates was an inspiring leader with a resoundingly positive attitude and deep knowledge of human nature. Briggs decided that if alpinism had something to do with the character of Bob Bates, then he’d take up the sport himself.

“This guy was real, and his positive attitude made life go better for everyone around him,” Bill remembers, “If he climbed, then so would I.”

During one of his mountaineering trips with Bob Bates, Briggs experienced a taste of mastery that would lead to his successful career as a mountaineer and guide. His group was traveling at night to reach a hut near Franconia Notch. The mercury crashed to 30 below zero F, wind howled, and one person keeled over from exhaustion. Briggs stayed in the rear and helped carry people’s packs, then took the lead, breaking trail through deep snow to the hut, thus allowing everyone to reach shelter. “It was a fabulous experience yet brutal — my mouth froze open,” recalls Briggs, “yet even with the hardship, I was looking around at how beautiful everything was; the stunted bushes coated with rime, snow formations; and the moon hanging above scudding clouds.”

At first, the Exeter staff was not supportive of Briggs’ skiing; they talked him out of joining the ski team, and recommended squash. The idea was that skiing would not be a lifelong sport; a theory that still elicits a hearty chuckle from Briggs. The teenager begged the Exeter dean for permission to skip church on Sunday and go to the ski hill. The dean agreed.

After that, Bill spent every Sunday schussing at North Conway, traveling there and back on the ski train. “Riding this train with all these skiers — singing to finish off a perfect day on skis — it was one of the best things I’d ever done.” To this day, aside from skiing, music is the great love of Briggs’ life.

Dartmouth College

Briggs went on to Dartmouth College where he immediately joined the famed Dartmouth Outing Club. During his first winter there (1953), he and several Outing Club members (John Moran and one other) traveled west on a ski trip. “At Sun Valley we paid for a lesson with Stein Eriksen.” Briggs laughs, “Basically, you just followed him down the mountain — if you could keep up.”

The next summer, they traveled to the Tetons for a climbing trip and bagged several first ascents, then headed for Canada’s Bugaboo Mountains — the first of several trips to the “Buggs” that Briggs came to know so well.

Winters at Dartmouth saw Briggs making several trips to Tuckerman Ravine on Mount Washington, where he skied progressively steeper terrain. “It scared the pants off me,” he says, “so I developed a slow speed turn with an uphill stem and a jump of both tails to quickly get into a turn.” Briggs discovered that the same attitudes which begat successful mountaineering also applied to steep skiing: risk assessment, careful planning, training, and conservative yet athletic technique.

“It all came about because of a mountaineering attitude,” he states. Practice paid off. Roberts French, Briggs’ later companion during the famed Bugaboos ski traverse, says, “‘Brigger’ was the most controlled, precise skier I’d ever seen.”

At Dartmouth, Briggs began playing stringed instruments and became quite the yodeler. One of his fond memories is of getting drunk at the fraternity hazings and spending most of the night in the top of a tree yodeling his heart out. “That was a good night,” he recalls.

Yet after Briggs’ breakthrough Exeter experience, Dartmouth was a letdown. The young man realized he didn’t fit in when, in a philosophy class, the professor asked the students who believed in free will to raise their hands. “I raised my hand immediately,” says Briggs, “and no one else did!” He and Dartmouth soon parted ways.

The parting was not easy, however, and Briggs fell into suicidal depression. “I found I couldn’t kill myself — I didn’t have the courage.” he says. “Since I had to live, I decided to make the most of life; to simply go with what I found most pleasurable: climbing, skiing, and music.” Briggs received his ski instructor certification in 1955 and immediately went to work teaching at Franconia in New Hampshire and for a period in Aspen, Colorado.

Teton Tea Party

But the mountain’s call was Briggs’ siren song; he returned to the Bugaboos in 1954 and 1955, finding that “the best way to get around was on skis.” During his visit to Aspen in 1956, he ski-toured the now classic high route between Aspen and Crested Butte. Then, after yet another visit to the Bugaboos, Briggs made an extended climbing trip in 1957 to Europe, where he and several companions made the first ascent of a long mixed route on Jaggavastin in Norway. “I then felt I’d qualify as a guide,” says Briggs, “and in 1958, I got on with Exum Guides in the Tetons. We started the Teton Tea Party that same year.”

The Teton Tea Party was a regular gathering of climbers and counter-culture types in the Jackson Hole area and has since become a part of North America’s mountaineering heritage.

Briggs and other climbers/musicians would start a fire under a bridge over the Snake River and play folk songs. The beverage du jour, Teton Tea, was an old tradition from the Briggs family, consisting of equal parts wine and strong tea, with lemon and sugar to taste. By the 1960s, the Tea Parties had become major events presided over by Briggs, eventually reaching mythical status as a sort of mountaineering Woodstock.

Bugaboo Ski Traverse

In the spring of 1958, Briggs felt his now familiar desire for the Bugaboo Mountains. In a resulting mountain epiphany, he conjured an expedition combining skiing, climbing, and exploration in one grand 100-mile traverse from the Bugaboo Mountains to Glacier Station (near Rogers Pass in British Columbia).

(Editor’s note: There seems to be some question as to whether this ski traverse occurred in the spring of 1958 or 1959. Some years ago, when interviewed by this author, Bill Briggs said it was 1959, hence the use of that date. We’ll change it if necessary once we get things verified. Participant Bob French left a comment and said it was 1958, so we’ll use that date.)

At the time, you couldn’t get useful maps of this area of Canada, and only one hut provided shelter along the way. To top that, no expeditions of this sort, using skis on technical glaciers and passes, had been attempted in North America.

Not that ski expeditions were unheard of, however. Briggs knew of Fridtjof Nansen’s well publicized traverse of Greenland in 1888 and wanted to show North America what terrific tools skis were for mountaineering. “There was something to be said,” he remembers in a moment of philosophical reflection.

At the time, Briggs was operating a ski school in Woodstock, Vermont. For instructors, he’d hired his climbing buddies from the Dartmouth Outing Club, including Barry Corbet, Roberts “Bob” French, and Sterling Neal. All were superb mountaineers, expert skiers, single, and ready for adventure. Briggs brought his Bugaboo ski traverse idea up with his crew. “I didn’t have to do any persuading,” he remembers, “These were all climbers and Exum Guides, and the idea was to go into an unexplored area — to be the first mountaineers there.”

Metal ski innovator Howard Head gave the men his latest skis, and they drilled holes in the tips so they could tie the skis together as tent supports or make an emergency sled if necessary. The group knew that weight was critical, and Briggs whittled the gear list to anorexic essentials, even questioning the inclusion of French’s harmonica (which they ended up bringing). Food was planned at 1.5 pounds per day, a minimal amount even by today’s standards. The group started out with 43-pound packs, an unusually light load for 10 days in the 1950s.

With all the planning, a skilled crew, and a bit of luck with weather, the visionary ski traverse went off mostly without a hitch. For 10 days, they climbed and skied through some of Canada’s most rugged unexplored mountains. They descended couloirs, crossed glaciers — even chased a cougar.

“We were at the head of a gentle glacier, and we spotted a cougar down on the nieve,” remembers Briggs with a hearty laugh, “We were in a playful mood, so we decided to give chase. We were skiing like mad down the glacier — the cougar would run away, look over his shoulder, then run farther.”

“So there we are, schussing down this glacier, playing in the mountains and throwing caution to the wind. Then I look down and notice we’re crossing a few small crevasses. Soon we skim a crevasse about a foot wide, then another that’s a couple of feet. By then, we’d forgotten about the cougar. Soon we’re jumping over wide crevasses and going too fast to pull around and stop. It really was something else; I remember thinking, ‘are these going to get too big?’ Lucky for us the angle eased off, and the crevasses never got any bigger.”

During the last day of the trip, Briggs made his crowning achievement as a navigator by bringing the group across the Illecillewaet Glacier in a fog, using only map and compass (a map was available for that section.) His heading dropped them into a narrow couloir, where the visibility improved, and they made glorious turns to within yards of their goal: a foot trail leading down to the Glacier train station.

The group had accomplished the first “high ski traverse” in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, and such ski traverses would gain popularity to the present. Briggs had expressed “what needed to be said.”

Exum Guide

Bill Briggs was coming into his own. The following summer, he became a full-fledged Exum Guide, and the next winter, he again directed the ski school in Vermont. Returning to the Bugaboos twice more during the next several years, on one trip, he used skis to approach a group of remote peaks known as the Four Squatters. During that trip, he made another first ascent and also filmed a movie. In 1961 he headed out to Mount Rainier and made an early ski descent that was close to being the first.

Music

Briggs’ hip continued to deteriorate, and in 1961 he decided to have the joint fused. The medicos said at best, he’d need to change to a sedentary life — at worst, he’d be in a wheelchair. In what can only be called hubris before the operation, Briggs built a cardboard splint that locked his hip, then tried to ski. Much to his delight and amazement, he could make turns with the immobilized joint! Even so, he knew he probably couldn’t lead the outdoor life of his past, and after the operation, he sank into depression.

Glen Exum assumed he’d be unable to do physical work, so Briggs lost his job as a guide. His fiancé left him and married another man, and another girlfriend he proposed to also left. Briggs tried to change careers while convalescing in Greenwich Village, N.Y. and played guitar in the Folk City Coffee House. “The problem with that,” laughs Bill, “was that just down the street, there was a guy named Bob Dylan packing them in; the coffee shop where I played was deserted.”

A few years after Greenwich Village, Briggs ended up jamming with Dylan at a Jackson Hole wedding where this shot was taken by photographer David J Swift.

Scientology

“Things were grim,” continues Briggs, “I went up to Hunter Mountain and tried to ski, but I sprained my knee getting off the chairlift. I could barely walk. Then a friend of a friend, Heidi Lockwood, came to my place and did a ‘Touch Assist,’ which is a part of Scientology that relieves physical trauma by using touch and visualization. It was the best treatment I’d ever had — it completely eliminated the pain and reduced the swelling. I did a long walk the next evening with no problems. From my point of view this was a miracle — I wanted to know more about where this came from.”

Briggs involved himself in Scientology and found himself developing “new abilities.”

“My reaction time had improved — I was playing ping-pong in my cast and winning,” Briggs remembers, ” I thought, there’s hope!” Soon after, he grabbed a pair of wire cutters, hacked his cast off, resumed teaching skiing, and married a former girlfriend.

With his newfound athletic prowess, Briggs knew he could continue mountaineering and skiing, so he moved back to Jackson Hole, began guiding again, and in 1966 became director of the ski school at Snow King Mountain (Jackson’s “town mountain”). Once back in Jackson, he pursued the outer limits of ski mountaineering, especially skiing the steeps.

“I was trying out my new abilities — testing — seeing what I could do — surprising myself,” remembers Briggs, “I’d been scared on Mount Washington’s Tuckerman; I was now skiing things just as steep as Tuckerman, such as Buck Mountain, and it was not that scary anymore — my focus was incredible.”

During those formative years, Briggs skied numerous peaks in the Tetons. In the spring of 1968, along with several other mountaineers, he made the first ski descent of the Teton’s most striking classic: Mount Moran via the Skillet Glacier. Rising 6,500 vertical feet from the glistening waters of Jackson Lake, the Skillet begs to be skied, and is counted as one of the five most classic ski descents in the Tetons. That was only a warm-up.

The Grand Teton

Briggs’ denouement was his now famous ski descent of Wyoming’s Grand Teton, the striking spire that lords over Grand Teton National Park.

After trying a solo ski of the Grand Teton and getting turned back by weather and bad conditions, Briggs enlisted the help of John Bolton, George Colon, and Robbie Garrett. On June 15, 1971, Briggs clipped his ski bindings at the top of the “Grand” and started down the 1,000 vertical foot east-face snowfield.

“I’d planned very carefully,” he remembers, “but you can’t predict everything. I didn’t know just how steep that skiing would be — it was really steep — and I didn’t know how much the snow was going to sluff off when I traversed across.”

Later, Briggs wrote: “Gusts of wind made balance uncertain, so I used great caution to get off the summit block. The snow above Ford’s Couloir was good for a few turns. Then I broke through, the skis sank about a foot into the snow unexpectedly and caused my first fall. I fell downhill, quickly rolled over, and stood up on the skis again. From there on, the snow was deep corn but quite skiable. Shortage of breath and strength forced me to make rather large turns down what can be called the upper Petzoldt Ridge. This got a little narrow between the cornice of Ford’s Couloir and the rocks. I actually skied into the rock at the narrowest place.”

Truly a man ahead (or in this case above) of his time, Briggs cut turns above fall-and-you-die cliffs, gingerly funneled himself into the narrows of the Stettner Couloir, rappelled over a big chock-stone and ice-fall to another skiable section, then finished in the bonus bowls of the Tepee Glacier which he remembers were “all frost feathers — the most interesting skiing I’ve ever done.”

The “Grand” was an impressive ski descent; in 1971, in North America, the only equivalent skiing was a descent by Fritz Stammberger on Colorado’s North Maroon Peak, and a route Sylvain Saudan skied on Mount Hood. Before 1971, very little euro-style steep skiing had been done on the continent, and North Americans didn’t understand extreme skiing.

Thus, the Jackson locals were nonchalant, if not skeptical, about Briggs’ feat. “I came back and said, ‘I skied the Grand yesterday,'” he remembers, “and people said, ‘uh huh.'”

Briggs needed proof, so he drove to the airport where there’s a good view of the upper snow face. To his delight, he could see his tracks with binoculars, so he called a photographer at the Jackson Hole News. The resulting aerial photograph (see the beginning of this article), clearly showing his tracks, is still a popular poster.

Slowing Down

After his Grand Teton descent, Briggs continued guiding and climbing but took a break from hard-core ski mountaineering. “It was hard to top the Grand,” he says. Then in 1974, the steep skiing bug bit him again, and he and a friend climbed Mount Owen with a ski descent in mind.

“I didn’t do as good a job as I’d done on the other peaks — I took a fall skiing for the camera,” remembers Briggs. “Luckily, I arrested before I got in too much trouble. That shook me up, and that was before the hard part, which was a super steep traverse going to the right; the wrong side with my fused hip. I had no choice but to do it strictly on my uphill ski, so I took a belay. Even with the rope, if I’d fallen on that side, I wouldn’t have been able to get back up! I was past my prime.”

It was time to retire from radical skiing. Briggs did so with grace, continuing his ski teaching and developing a method of instruction held in high esteem by some of Jackson Hole’s best guides and ski instructors.

Presently, Bill Briggs is a well-known local musician and yodeler in Jackson Hole, and greatly respected in North America for his pioneering role in ‘ski mountaineering,’ the term he prefers over ‘extreme skiing.’

“I don’t call the skiing I did ‘extreme,'” Bill explains, “this was mountaineering; this was being careful. This was not jumping off cliffs — I really want to make that distinction.”

Aside from stunt-like ‘extreme’ skiing, Briggs is happy with the current style of ski mountaineering. “I think the emphasis is really good, it is and should be a growing sport. We have these guys we can hand the sport off to; but it’s important they keep their heritage in mind.” To that end, a large part of Briggs’ life still involves writing about and teaching skiing.

Above all, Briggs is concerned about humans taking responsibility for their actions and world. “I’d like to see mountaineering help people achieve higher levels of responsibility,” he states. “The first level being simply taking care of yourself and not depending on other people…so whatever I do learn, I want to be able to pass it on. That’s my game, it’s not everybody’s game, but it’s mine.”

Related Links:

Bill Briggs was inducted into the U.S. Ski Hall of Fame in 2009.

Mort Lund article about Bill in 1979 Ski Magazine

Portions of this writing are published in Louis Dawson’s ski mountaineering history book “WildSnow” and an article similar to that above was published in Couloir Magazine Volume VIII-3, February/March 1996. Thanks goes to Bill Briggs, Craig Dostie, Tom Turiano, and Jon Waterman for their support of the WildSnow history project and help with the original versions of this article.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.