The next installment of the Adventure From Home Series focuses on the Elk Mountains near Aspen, Colorado. Check out the first round, focused on the Tetons. I was excited to be introduced to this new-to-me range while connecting up with close friends living in the area.

The Elk Mountains are a proud subrange of the Colorado Rockies. The majority of the range is located in the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness and larger White River National Forest. The rock quality is poor, the snowpack is generally unstable, and the amount of remote ski terrain is seemingly endless. This combination of challenging conditions and inspiring terrain breeds a rich skiing history and passionate backcountry community.

When visiting the Elks, I planned out two separate ski days instead of a two day overnight trip. This allowed me to ski with different friends while in town: Aidan and Mike. Aidan and I met in university and started skiing together while both living in the Eagle Valley. He’s a thoughtful backcountry skier that now works as a high school science teacher in Basalt (as well as occasional contributor to WildSnow). Mike and I met last year while working for Cripple Creek Backcountry. Mike has a ferocious work ethic that he applies to his career at Cripple Creek, his skiing ambitions, and his personal relationships. It’s a truly admirable quality of his.

Aside from skiing in the Elks, I was able to chat with two role models of mine from the area: prolific ski mountaineer Chris Davenport and guide service owner Amos Whiting. Our conversations are chopped up into helpful local knowledge tidbits inside the Plan section of the post.

Plan

To educate myself more on the Elks, the local history, and the snowpack in the area, I spoke with long time locals Chris Davenport (ski mountaineer and nice guy) and Amos Whiting (Aspen Expeditions co-owner, lead guide and also nice guy).

An Elk Mountains history lesson and culture chat with Chris Davenport

My conversation with local legend/skier extraordinaire Chris Davenport turned into a full-fledged history lesson of skiing in the Elks:

Aspen has been the center of human-powered skiing in the United States for a long time. It largely started in 1942 with the 10th Mountain Division training for winter warfare out of Camp Hale (east of Aspen). The training center localized mountain knowledge/talent/energy to the central Colorado area from around the country. From near Camp Hale, infantry members made the legendary Trooper Traverse from Leadville to Aspen in February, 1944. This sparked the idea of ski touring in the area when skiing altogether barely existed as a sport in the US.

Post WWII, many 10th Mountain Division veterans returned to Colorado, bringing with them a passion for backcountry skiing and exposure European ski culture/ideas. A few notable vets who returned to the US with mountain ambitions were:

Fritz Benedict: founder of the 10th Mountain Division Memorial Hut System

Bill Dunaway: first ski descent on the north side of Mont Blanc and longtime Aspen newspaperman

Paul Petzoldt: founder of NOLS and prolific North American mountaineer

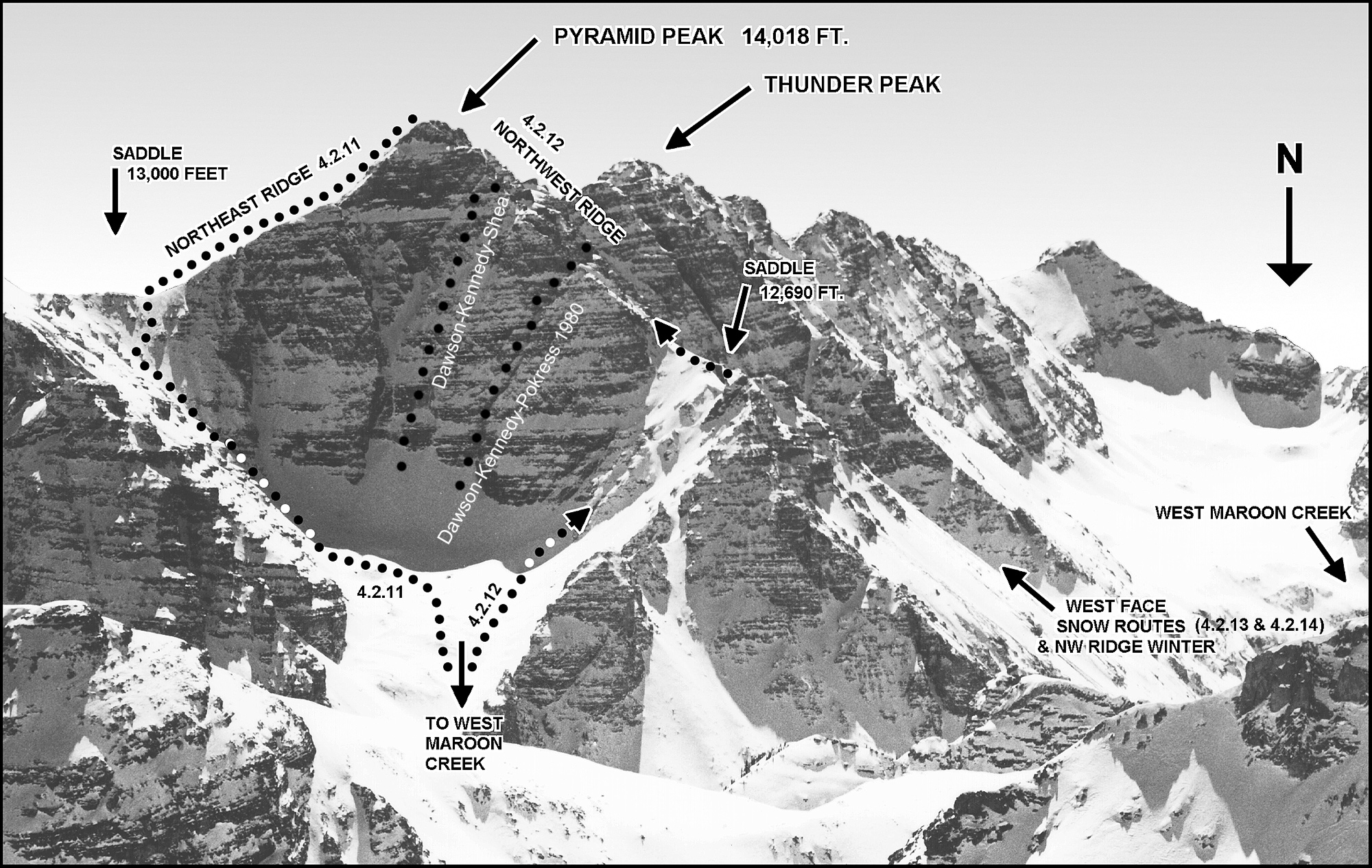

The culture of ski touring and ski mountaineering persisted in the Elks. The generation after the 10th Mountain Division continued pushing and developing the sport through innovative ski descents. In 1971, Fritz Stammberger skied the North Face of North Maroon (solo with no ropes). This shook the country and largely redefined steep skiing for North America*. The general momentum of skiing and mountaineering continued. Chris Landry (his father was a Lieutenant in the 10th Mountain Division) made the first descent of the east face of Pyramid Peak in 1978. The line stood unrepeated until 2006 when Chris Davenport, Neil Beidleman and Ted Mahon made the second descent (they built on the style of the line by completing a descent without rappelling). In recent history, locals Max Taam, Pete Gaston and John Gaston linked together three notable Elk Range 14ers — North Maroon, South Maroon, and Pyramid Peak — in a day..!

The Elks have a long and storied ski mountaineering history, with big committing lines like those on Pyramid Peak.

This progression speaks to the passing of the torch from generation to generation within the Aspen ski community. Chris Davenport mentioned: “The goal is to not just to ski, but how can you add something to the progress of the sport? How can you add a chapter to the history book? It’s important to me [and other Aspen locals] to add to the legacy of ski history in Colorado.”

However, it’s easy to idealize the rich ski history in Aspen. Chris adds, “Aspen also has a history of tragedy. Ski mountaineering is dangerous. The mountains are steep. The rock is poor. The snowpack is unstable. There is a heightened sense of responsibility and safety within the community because of those dangers and experienced tragedy around the sport. It’s easy to only see the highlight reel, but what you don’t see is the experience and dedication required to ski safely and return home. It’s a long residency in the mountains and important to not immediately rush to the biggest and most consequential lines.” This idea of slow progress and patience is a resounding point that stuck with me most from my conversation with Chris.

Elk’s Snowpack Overview and Decision-Making Talk with Amos Whiting

My interview with Amos Whiting (crusher climber, skier, business owner and rad dad) proved fruitful for gaining a better understanding of the snowpack in the Elks. Amos is co-owner and lead guide at the local guiding service Aspen Expeditions. In the winters, he guides backcountry skiing and teaches avalanche courses. This means he ‘interacts with the snow’ (his verbiage) almost every day of the season. This daily level of exposure to the weather and snow is helpful for building a deeper understanding for the Elk’s continental snowpack. The ‘story of the snowpack’ (another Amos-ism) in the Elks is complex. It creates challenging decision making for skiing. The 20/21 season’s story is as follows:

— An October storm and little snow in November created a poor structural foundation

— Smaller storms in December and one big storm over the new year built a touchy base to make for good, albeit dangerous, ski conditions

— High pressure and little snow in January and February faceted the snowpack and weakened the already sensitive structure

— Low snow totals led to exposed rocks accelerating melting at lower elevations in March

The big event that stabilized avalanche terrain was a warm week in late March. This created a lot of running water in the snowpack that uniformed the multiple weak layers in the snow. It also created a big wet slab avalanche cycle that stripped a lot of terrain of snow.

April then got cold again which created a stable foundation for new snow to fall on top of. Since then, the challenge is managing upper pack instabilities (i.e. storm slab, wind slab and wet loose avalanche problems)

Understanding the story of the snowpack will help you understand the mechanism behind the structure of the snow. Amos includes, “If you don’t spend a season with your head in the snow, get this synopsis from a local in the area to build a foundation of understanding for your decision making in that terrain.”

For managing complex terrain and a challenging snowpack like in the Elks, Amos provided a helpful proverb for decision-making: “Terrain is always your friend and snowpack is always your enemy.” He’s saying that we have complete control over our terrain choice, and no control over the snowpack. So, learn to understand the snowpack and manage terrain choice accordingly.

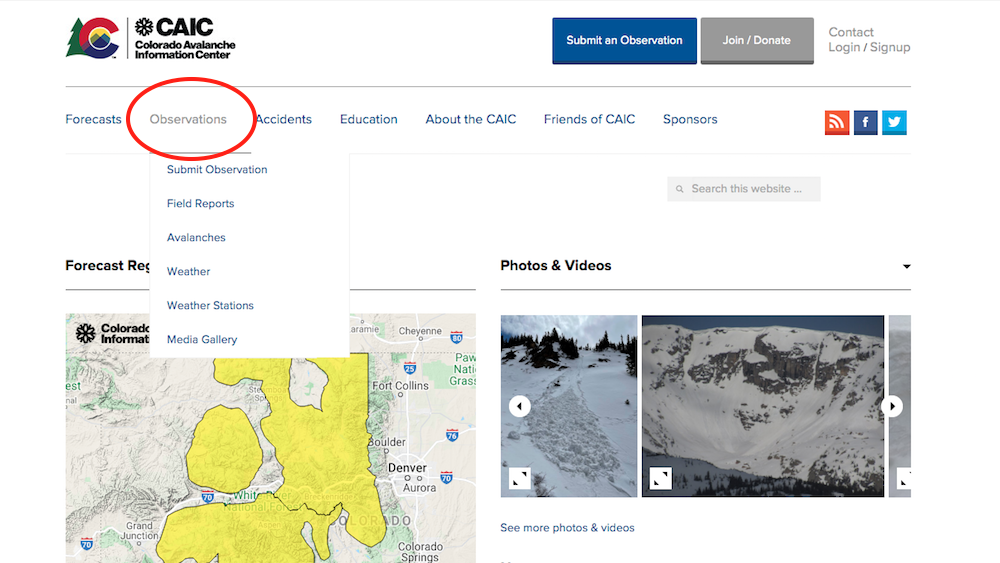

The best way to build the narrative of the snowpack anywhere in Colorado is through the Observations tab on the CAIC. Look through Archived Forecasts, Field Reports, and Recent Avalanches.

Pre-trip prep with the onX Backcountry app

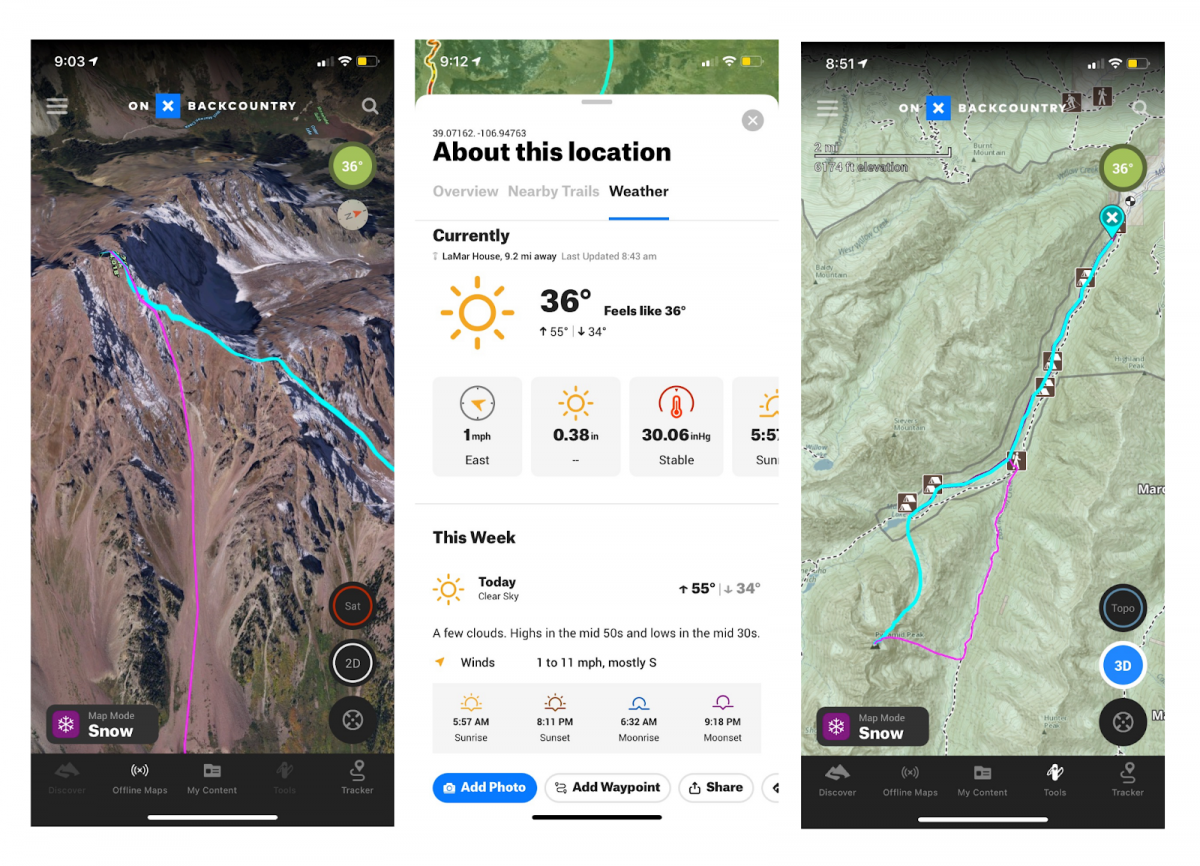

My primary objective while in the Elks was to ski the east face of Pyramid Peak with Aidan. Mike and my plans focused instead on finding the best snow, rather than a particular objective (These two days highlight the difference in decision-making between objective-based and conditions-based skiing). To be well-informed upon arrival, I kept tabs on the following conditions and trends:

— Above-tree-line snowpack and avalanche problems

— Local weather for elevations above 10,000′

— High alpine skiing quality

Trip planning information for Pyramid Peak.

Left: The 3D Sat view of Pyramid Peak helps with route finding. A higher resolution and winter imagery would significantly improve this app feature.

Center: Point forecasting for the area is convenient to localize the weather forecast (The captured forecast was for a different date than our descent).

Right: Our ascent is in blue and descent in pink.

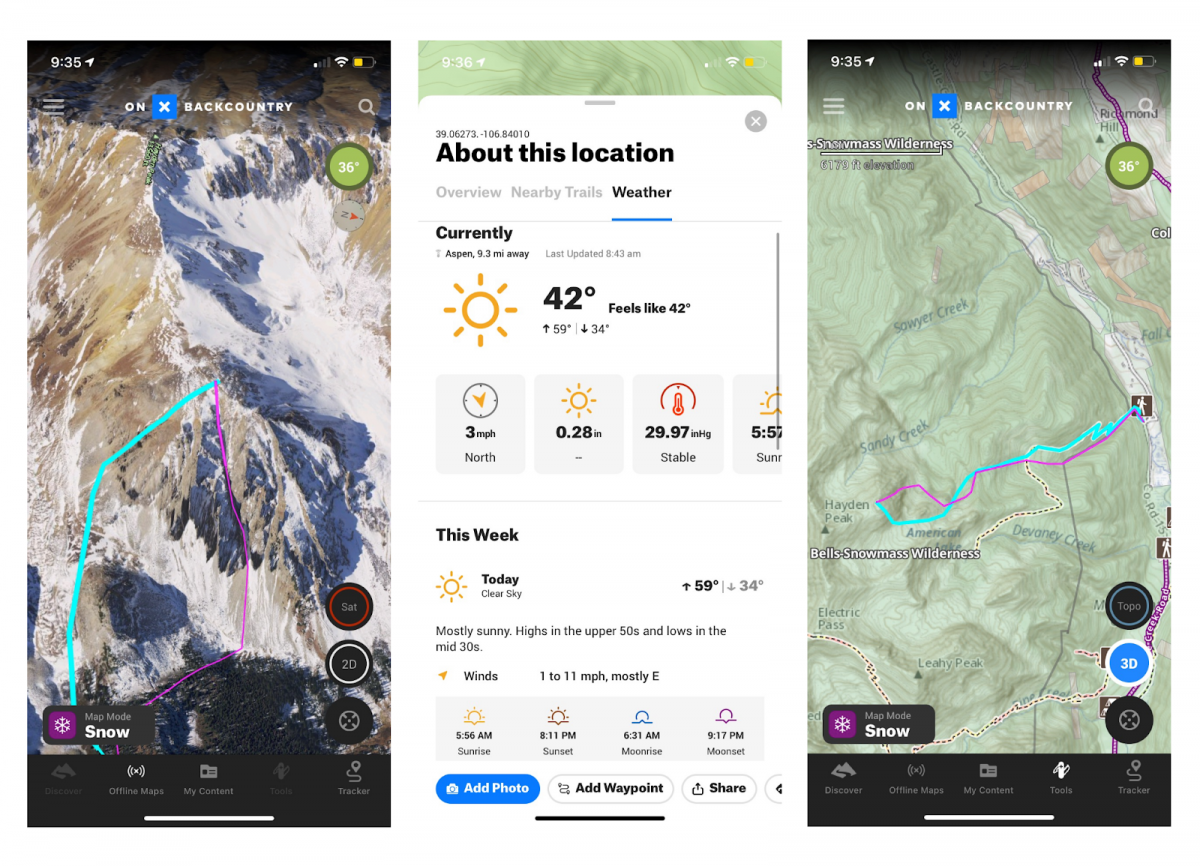

Here are similar trip planning screenshots from the Onx Backcountry app for our descent near Hayden Peak (from right to left):

Left: This 3D Sat image has a bit of snow on it to help better visualize winter terrain.

Middle: The point forecasting is one of OnX Backcountry’s best features.

Right: Our ascent in blue included ~500’ of trail hiking; our descent in pink was able to get us within five minutes of the car with skis on!

Early April’s warm weather created a web slab avalanche cycle. I saw a lot of those slides reported on CAIC Avalanche Observations. Friends in Aspen said that the skiing in April was good if you could avoid refrozen debris from the early-April cycle. They also said that Pyramid Peak’s east face looked thin and in challenging condition. Cold weather in mid-April locked up the snowpack, creating a stable foundation for *hopefully incoming* sticky spring storms. For a try on Pyramid Peak, we waited for a warm storm with low winds and persisting cloud cover the preceding day.

I called Aidan to make sure we were on the same page with our goals, expectations, and risk management. From our combined interpretation of the snow conditions and forecasted weather, we decided to give Pyramid Peak a try. Mike and I planned to ski the preceding day with no specific objectives, but just hoping to find good snow and spend a low-stress day in the mountains.

Tune in to Part II to find out how the planning panned out when the skis hit the snow.

*Coincidently, two other iconic steep skiing descents took place that same year. Bill Briggs made the first descent of Grand Teton and Sylvian Saudan skied the Newton-Clark Headwall on Mount Hood.

Slator Aplin lives in the San Juans. He enjoys time spent in the mountains, pastries paired with coffee, and adventures-gone-wrong. You can often find him outside Telluride’s local bakery — Baked in Telluride.