An old maxim says “no research is better than bad research.” Thus, I’ve tended to ignore industry sponsored and otherwise suspect studies on how effective avalanche airbags really are. Instead, my gut has been my guide.

All I had to do was look at the dismal and well proven metrics that show being buried in an avalanche is often a death sentence — stats that show the best shovels and beacons might not make much difference. At risk of stating the obvious: NOT being buried is key. So, how not to be entrained if you do get caught in a slide? It’s obvious to most backcountry skiers that airbags can do the trick; avoiding burial by floating you in the debris flow. Yes, airbag behavior is indeed well proven by both real-world testing, observation, and physics (Brazil nut effect).

Yet individuals using airbags still die in avalanches.

Thus, avalanche airbags are no more a panacea than ski helmets are to head injuries, begging the question: assuming the airbag CAN SOMETIMES save your life, just how likely is that wonderful occurrence, in comparison to leaving your balloon at home?

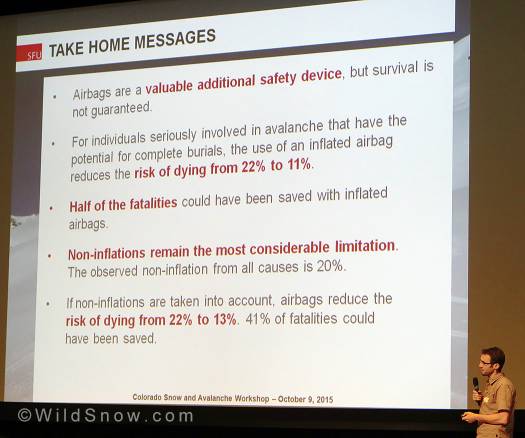

At the Colorado Snow and Avalanche Workshop a few days ago, Dr. Pascal Haegeli presented his 2014 epidemiology study of avalanche airbag effectiveness. Haegeli was convincing. His conclusions? Your risk of deadly avalanche burial is reduced about 11 percentage points, from 22% to 11%, if you’re wearing an inflated balloon pack while caught in a slide large enough to bury you.

Here is the summary from the abstract at Resuscitation Journal: Binomial linear regression models showed main effects for airbag use, avalanche size and injuries on critical burial, and for grade of burial, injuries and avalanche size on mortality. The adjusted risk of critical burial is 47% with non-inflated airbags and 20% with inflated airbags. The adjusted mortality is 44% for critically buried victims and 3% for non-critically buried victims. The adjusted absolute mortality reduction for inflated airbags is ?11 percentage points (22% to 11%; 95% confidence interval: ?4 to ?18 percentage points) and adjusted risk ratio is 0.51 (95% confidence interval: 0.29 to 0.72). Overall non-inflation rate is 20%, 60% of which is attributed to deployment failure by the user.

Haegeli explained that his study was done the same way medical treatments are evaluated. You use a control group and a treatment group, then compare outcomes. The challenge regarding airbags, and the possible flaw in this study, is that Haegeli and his colleagues had to actively pick the avalanche accidents they included in their study instead of using random double-blind groups of “patients.” The selection process sounded rather complex, idea being they went out and found accidents involving large enough avalanches to bury and kill a person. They then compared one group of accidents wherein airbags were used, and another set of accidents without airbags.

Interestingly “non-deployment remains the most considerable limitation to effectiveness.” Haegeli and his fellow boffins found an airbag non-inflation rate of 20%, over half of which was caused by the user failing to trigger (with the remainder caused by mechanical failure or damage.) While encouraging, the 11 percentage point increase in survival is said to not be as good as that reported in other studies which leads me to some thoughts regarding airbags that didn’t work.

First, one wonders if they wrapped the user-error non inflations back into their numbers and counted a percentage of them as imaginary saves, would that bring these numbers back up to those of other studies? In real life, it’s stunning that about 10% of the time someone gets killed while wearing a balloon pack, it could be the fault of user error in not pulling the cord! This makes a very very strong case for practicing inflations and being sure your airbag trigger and hand glove combination work easily together — and that you do NOT HESITATE to trigger if you’re caught in a slide.

Second, those pesky leg straps. I can count in the hundreds the number of people I’ve seen skiing in avy terrain, all prettied up with helmets, airbags, beacons and on and on, who did not have their leg-crotch straps fastened. In his presentation, Haegeli related an example of a death while wearing inflated airbag, caused by the user not using his leg straps and the airbag backpack riding up under his armpits, pinning his arms, with the sternum strap strangling him.

Third and perhaps most import: elephant in the room is that avalanches are violent — some (if not most) so violent an airbag is not going to save you. This is especially true in terrain where the slide could do one or all of the following: 1) Cause you to essentially fall down a mountain; 2) Cause you to collide at high speed with immovable objects such as trees or sharp objects that puncture the balloon; 3) Be so large and violent that trauma from the moving snow itself is deadly.

Considering the above, airbags will never be 100% effective. But you can enhance the protection of your airbag pack by doing a couple of things. Mainly, be sure you can and will trigger your balloon immediately — at the slightest hint of an avalanche. Perhaps as importantly, be terrain aware. Airbags are obviously remarkably effective (see countless Youtube videos) in moderate to smaller slides without terrain trauma issues such as trees. Thus, perhaps airbag users need to shift traditional terrain management. For example, a group of skiers sporting airbag backpacks could be wiser choosing a somewhat larger yet open bowl, as opposed to a smaller yet timbered or rock studded ski run. “Let’s ski the trees!” might not be the wisest choice.

With 100% airbag use by skiers in avalanche terrain, along with wise route choices, perhaps Pascal Haegeli’s next study will show a much more remarkable increase in avalanche survival.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.