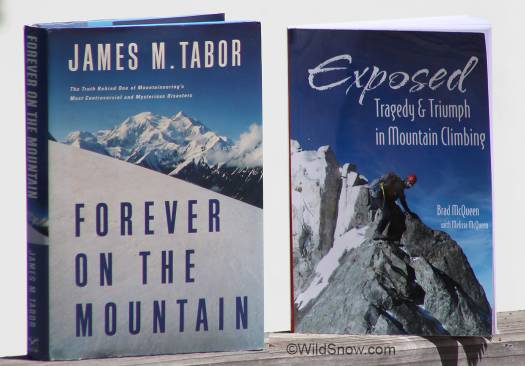

Dire duo. Note that many other books have been written about the Denali Wilcox 1967 tragedy, I link to a few of them below.

We learn from each other’s mistakes — and our own. Hopefully. Even so, when it comes to book reviews I’m not a fan of the tragic exposé, whether it be first or second person. While it’s true I dabble in accident analysis now and then, I don’t prefer dwelling on the negative for the time it takes to read a book. Especially if it’s a lengthy tome — especially if it’s about something that could easily happen to myself, friends or loved ones.

Thus, I found James M. Tabor’s “Forever on the Mountain” to be compelling, while painful. This 400 page forensic analysis wrestles with one of North American mountaineering’s worst disasters, that of seven men’s deaths on Denali (Mount McKinley) in 1967. Known as the “Wilcox” expedition (after Joe Wilcox, the leader), the ill fated climb was fraught with everything from gear failures to an excessively powerful storm — yet in my opinion human error was the root of most, if not all.

Over many years, thanks to written accounts I’ve learned much from the 1967 disaster. The learning probably saved my life and that of many friends — more than once. That’s a small silver lining in a very dark cloud. The sad part, the painful part, is simply what a comedy of errors the 1967 climb was. I grimaced when I read about it in the 1970s, and I grimaced anew while reading Tabor’s book.

The story begins and ends with the ineptitude of the Park Service. But the climbers themselves didn’t help matters. While author Tabor seems to effort at declaring what experts most of the participants were, on the whole they appeared to me in the reading to have little experience with expedition living, not to mention truly cold weather climbing and high altitude. If there is any priority of resume lines you want on a Muldrow Glacier Denali climber’s resume, those three are the top. Rock climbing experience is at the bottom of the list, and even ice climbing isn’t that important a skill. The Muldrow route on Denali is a gigantic dangerous slog. Getting along with your mates and being a good cook are as important as how tightly you can strap on a pair of crampons. Though the latter can come in handy.

For those who don’t know my history, I should mention that I’ve climbed Denali twice. Once in 1973 by the same Muldrow Glacier route as the Wilcox group, and recently in 2010 (see our Denali category here at WildSnow). Both trips were successful. How much of that was luck, and how much was due to knowing and attempting to avoid the dire mistakes of 1967? I can say that we did have some hard and fast rules for our behavior in 1973 — some of the exact rules ignored or broken in 1967. Examples being 1.)Wands must be placed, well. 2.)Don’t tent in the vicinity of Denali Pass, dig a snow cave. 3. Optimus 11B stoves should be used outside if possible, and never refueled inside a tent.

Despite the 1967 disaster still being somewhat mysterious (no diaries, cameras or other were recovered from the deceased), the sad take you get from second guessing the whole deal is this: IF the summit route had been correctly wanded, and IF a commodious snowcave had been dug at their upper camp on Harper Glacier, all the men quite possibly would have lived. Along with that, the two men at high camp would almost certainly have lived.

Facts are the expedition’s first summit team made a tragic and obvious mistake in not adequately wanding the summit section of the route. In my opinion this was the root cause of five men (second summit team) becoming stranded on the flanks of Denali with no way of returning to their camp. At first, the poor wanding got them lost and caused a bivouac that delayed their summit by a full day! Then a storm hit, and one assumes the crew remained in their bivvy due to uncertainty about being able to descend on-route in severe weather. With good wands, they would have easily made it up and down the peak well before the storm — while later, perhaps they could have still struggled downwards from wand to wand, as numerous Denali climbers have experienced since.

Of course the fact remains that the two individuals at high camp also died, most probably due to inadequate tents and failure to snow cave. I believe if the group had been reunited at high camp, their strength in numbers might have resulted in a better outcome. For example, they could have teamed out for wind wall building and snowcave construction. I could go on, but my hindsight quotient is well exhausted.

To be fair, present Denali safety philosophy is indeed that you do ANYTHING within reason to escape the upper mountain and return to camp if a storm brews. That ethos quite possibly evolved from the Wilcox disaster, and the poor boys in 1967 simply never thought that way. Moreover, they did not have the weather reports nor the reliable lightweight radios and satphones we have today. In the case of weather, much of the writing about the Wilcox disaster blames an extreme storm to at least some extent. Wind was certainly the nail in the coffin, but the famous winter expedition of 1967 survived an “extreme” storm and high bivvy. What is more, everyone else on the mountain at the time survived despite the storm. So I don’t entirely buy the “blame nature” theory.

As for the style of camping shelters (tents that shredded in the wind) and their ensuing inadequacy, perhaps in 1967 Denali had still not shown her teeth. Later, thanks to the Wilcox guys having been bitten, our 1973 expedition spent nine days in a storm on Denali Pass, easily survived in well stocked snow caves. It wasn’t easy digging those holes through icy snow, and multiple carries were required to get all our food and fuel up that high. Clearly, if it had not been for what happened in ’67 we might not have taken the mountain so seriously.

Back to the Park Service. The 1967 debacle began when Park officials forced two separate expeditions to act as one, due to the bogus idea that bigger numbers equaled more safety. Instead, discord and friction between the two groups eroded their ability to make good group decisions — not to mention the insidious bugger of increasing the overall stress level. Adding to the tragedy, while rescue might have been impossible, all attempts at helping the climbers were muffed to a degree that’s difficult to believe.

But don’t take my word. James Tabor digs into the 1967 Wilcox tragedy from every angle imaginable — including interviews of principle players. If you’re planning a Denali trip, read “Forever on the Mountain” to know just how bad things can get. As for an armchair page turner, you’ll probably get through it but expect the hideous details to haunt your dreams for at least a few nights.

Like I said, I don’t want to dwell on books about tragedy. So instead of breaking out to separate reviews let’s make this a pair.

“Forever on the Mountain” is about a group’s obvious lack of overall ability, combined with horrible circumstances and numerous mistakes. In contrast, Brad McQueen’s “Exposed” covers navigation errors and an unplanned bivvy that are clearly on the ineptitude side of the equation. It’s thus a better cautionary tale for the average climber. (Though if you’re headed for Denali, ALWAYS read up on the Wilcox affair.)

A pet peeve of mine for years is how the thousands of “14er baggers” (climbers of 14,000 foot peaks) in Colorado simply do not take our mountains seriously enough. “Exposed” begins with exactly that. An almost comically inept group of hikers set out to do a peak. They climb the wrong mountain. Even then, redemption was available by simply walking a ridge connecting them to the correct peak. Instead, they scramble down a ridge in nearly the opposite direction.

The group eventually drops to a road (closed) and an emergency phone. They don’t use the phone and instead decide to hike back up and over their original objective, 14,264 foot Mount Evans. They make the summit, somewhat spent. A lengthy descent begins. They have fido along, and end up using a makeshift litter to lift the pooch over rocky areas, using precious energy and time that’s fast dwindling — as is daylight. A storm brews. No headlamps. No effective fire starting kit. The three climbers bivouac in a willow thicket a half mile from their parked car. Benighted in a cold snowstorm, they nearly die from hypothermia. As fido snores, the author’s wife’s toes freeze off. In the morning the author walks out in 20 minutes. A helicopter hauls his father and wife. Amputation ensues.

While excessively wordy (some of it reads like it was dictated and transcribed), the first part of “Exposed” worked for me. It ends up being a somewhat didactic study of how wrong things can get in the mountains — a wakeup call. Common wisdom is that nearly all injurious situations in the mountains happen through a chain of bad decisions and events that are often avoidable. To author McQueen’s credit, he’s 100% open about the “chain” and all the bad decisions that led to the outcome.

Not to wax smug here, I’ve made my mistakes. In particular, I’ve been lost plenty of times. Usually, just as happened to author McQueen, the bewilderment has been of my own doing. I’ve also been caught by a lack of preparation (as on Mount Elbert last year, when I didn’t prepare my gps correctly), and just plain laziness has nailed me plenty of other times. My partners used to have a name for it, perhaps they still do. They called it being “Dawsonized.”

What I’ve learned along the way is that mistakes will be made, but blunders need not result in dire consequences. The golden rule is, indeed, to take the mountains seriously. Prepare navigation at home, even for the easiest peaks. Carry a map, compass, and a GPS you’ve prepped with waypoints and perhaps even a breadcrumb trail. Leave pets at home unless you’re familiar with the route and are certain the canine is appropriate. Allow plenty of time for the ramble (summit by noon!). As for gear, yes, it’s not a substitute for your brain. Nonetheless, organizing and carrying the “10 essentials” inspires an intellectual and caring attitude. As the saying goes, “bring emergency gear and you probably won’t need it.”

Moreover, another idea of the “10 essentials” is redundancy. Forget your headlamp? Start a fire and wait till morning. Not enough food? Your headlamp keeps you moving at night so you don’t starve during a bivvy. Partner doesn’t have enough clothing? Give them your extra layer.

Back to “Exposed.” The remainder of the book is author McQueen’s account of his climbing career, intermixed with a thread of personal life. It has its gems (e.g., keeping what sounds like a sweet marriage going strong), but they’re overshadowed by lengthy and wordy writing. I found myself skimming. Worthy vignettes of introspection flesh out blow-by-blow accounts of climbs, frequently guided, that could have been summed up in a few pages. Moreover, too much personal detail weighs things down. I can relate to gluten intolerance, but do we even need the word “colonoscopy” included in a climbing book?

For myself as an experienced alpinist, reading me-and-joe accounts of guided climbs just didn’t do it. Nonetheless, I’d say “Exposed” would appeal to a less experienced alpinist who was in the nascent stages of their mountain life. Perhaps they’d be aspiring to Denali or other iconic summits — and they’ll do well to know how guided climbing proceeds — as well as the basics of safety.

Perhaps most importantly, my hope is that as the 14er “bagging” season begins here in Colorado, the publication of “Exposed” will help reduce what is sometimes best termed a clown act, what with folks doing the human snow toboggan without ice axes, stumbling like herds of zombies from afternoon lightning, bringing so many dogs they need a pet wrangler to keep track of the herd — and generally climbing under-equipped.

On the gear side, perhaps the best way to bring it all home is to revisit the concept of the “10 Essentials.” McQueen provides a “10” list in his appendix, along with other safety tips that’ll help aspiring 14er baggers. Below, my own list of essentials for rambling in mountain ranges such as the Alps or Colorado Mountains.

Remember that the TEN ESSENTIALS means exactly that. All this stuff can be downsized and made amazingly lightweight for moderate objectives, but it should all be carried for anything but the most straightforward hiking on prepared trails.

1.Navigation (Prepare at home, GPS works well but do your homework. Carry at least a miniaturized paper map for all but the most familiar routes. Small compass is not optional, always bring for even the most familiar routes. One of the most common “lost” scenarios is when you’re overtaken by a heavy overcast that totally obscures the sun. You totally lose your sense of direction. A quick glance at a compass can make this a trivial event. Otherwise…)

2. Communication (In my opinion, not optional. Standard of care and the “social contract” is now at least a SPOT unit, or a cell phone if you know you have coverage. After quite a bit of testing by myself and other WildSnow gear reviewers, I also recommend the SPOT/Globalstar satphone as well as the Delorme inReach.)

3. Adequate clothing (No cotton, no jeans. At least a full-on shell jacket and perhaps shell pants as well.)

4. Light source (Tiny but still bright headlamps are an easy purchase, you should never go without. Due to battery concerns, don’t depend on a cell phone flashlight app.)

5. Fire (When you actually need it in an emergent situation, starting a fire can be difficult. Carry an immersion proof fire starting kit you’ve practiced with and is intended to work with damp fuel. Vaseline soaked cotton balls in a plastic bag do the job — so long as you’ve got a flame source.)

6. Tools (Could be just a knife, or more elaborate repair kit carried during lengthy ski trips.)

7. Food (No need to get excessive, but bring enough to keep your blood sugar up if you’re stranded overnight. Victuals stronger in protein and fat content are better in bivvy. Time for a stop at the jerky shop.)

8. Water (Bring appropriate amount for your objective, and a little extra. If you do end up in a “situation,” prevent freezing by storing your bottle inside your jacket.)

9. Sun protection (Compromised vision or a bad sunburn can trigger or contribute to the accident chain. Remember your sunglasses and sunscreen.)

10. Shelter (Some lists recommend an actual bivy sack or waterproof blanket. In my opinion, good quality shell garments also count as “shelter” and you should carry what you deem appropriate give your style and objective. Examples: if you’re leading a large group of inexperienced hikers on a backcountry trail, you might well carry a small lightweight bivvy sack. If you’re an experienced crew with a reasonable objective, close to civilization, you’ll probably just depend on having good clothing.)

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.