During spring of 1981 I was in Chile with my friend and climbing partner Rich Jack. So going back there several weeks ago was a nostalgia hit along with a fun dose of adventure travel. Our 1981 trip lasted three months. After nearly four weeks of skiing at Portillo (and before that failing on a couple of big Andes alpine climbs in Peru), we bypassed the closer Santiago region and headed farther south for the town of Osorno, where we planned on skiing a few volcanoes. Due to weather and transportation issues we only got up Villarica Volcano (fun back then, and still popular.) Honestly, I never thought I’d be back. I like Chile, but my home mountains in Colorado and the European Alps seem to be the ranges that call me.

Chile is huge, 2,610 miles north/south. Extending for much of those miles something like 4,000 volcanoes and the Andes mountains result in one of the most prolific collection of peaks in the world; when combined with Peru and Argentina, way more mountains than the Alps, perhaps even exceeding the North American northern-west coast ranges. Much of the Andes range is roadless. Even though parts of Chile are more roaded than most people assume, very little access is as easy as you get in western Europe. Thus, as happens in the North America, the places with road access to the alpine do become popular. Those are the areas I focused on during this trip, though “popular” is a relative term. (If you go outside those zones you’re looking at overnight trips supported by pack animals or your own back.)

Our new Chilean friend Casey Earle picked me up at Las Trancas after the Marker Kingpin tech binding event. We’d had terrible weather: scouring winds in the highlands and torrential rain at lower elevations. As optimists, Casey and I stayed a few more nights in Las Trancas thinking we could get up on the Nevados Chillan volcanoes for some touring. We were totally shut down.

My luxury stay during the Marker press event at Rocanegra was impressive, but wasn’t the real Chile you get if you’re a middle to low budget adventure traveler. Moving to Chil-in at Las Trancas gave me a soft re-entry into the world of less costly lodging that’s one of the more interesting aspects of South American ski travel.

What makes it “interesting” is you simply don’t know what you’re going to get. For example, the showers at Chil-in were hot and powerful, in bathrooms down the hall. At Rocanegra you had a bathroom in your room, but the shower stayed cool unless you ran it forever. Chil-in served good solid food but it wasn’t fancy. Rocanegra served the cuisine of a luxury European hotel. The great equalizer is Chilean wine. I was quaffing complimentary wine at Rocanegra that tasted like a $50 bottle from Napa; later we were buying that same wine for $5.00 USD a bottle in quaint regional mercados. In either case, who cares how the showers perform?

South of Las Trancas you get into the real Chilean “Lake District,” where beautiful shinning white volcanoes rise as perfect cones above glistening blue “lagunas.” I’d talked about heading down there to the town of Osorno again, but the weather looked bad. In contrast to 1981 I was amazed at how easy it was to get accurate weather reports, and thus simply escape rather than waiting. Back in the day we had nearly zero sense of what the weather was doing. With no cell phones and no internet, whatever weather reports did exist were difficult to find when we were out of the city, and of course what we could get was in Spanish and had to be translated. My Spanish was ok back then (mostly forgotten now, sadly), but reading always took time because new vocabulary words had to be looked up in a paper dictionary.

While we were enduring fire-hose rain at Las Trancas, the weather website was hinting that northern was better. So Casey offered to drive me up to Santiago by way of Corralco ski resort on Vulcan Lonquimay — tourism guided by a local, always appreciated. On the way, we spent another few nights at a high quality hostel with Swiss heritage and did get some skiing in.

Again, the crazy contrasts of Chilean lodging were evident at the Suizandina Lodge near Lonquimay. To my surprise, I was suddenly in the midst of a German/Swiss heritage hospitality culture replete with tile stove and kuken. All the signs were in German, Spanish and English. Founded by a Swiss guy, the place was more put together than even Rocanegra. The showers worked, and the owner was up on ski touring in the area. Prices were a bit high but staying in the dorm cabin (with kitchen) didn’t blow my budget.

Luis Gomez makes his own splitboards in Lonquimay. He showed us some of their nearby lower altitude terrain that’s reached by plowed roads or snowmobile. Looked good. He’s standing in front of a motel he helps manage, the “Rustiko” which shows a style of building and woodworking that seems to be some sort of Chilean cultural phenomenon. Wood is everywhere, carved into fantastic shapes, lamp covers made from stumps, siding made from big thick sawmill slabside. The overall effect is aesthetically overwhelming, but fun (though after a few glasses of Chilean vino enhance your senses you might find yourself yearning for the simplicity of a snow cave).

We got some skiing in on Corralco along with a short tour in gale force winds. The storms continued, ever wetter, so we finished our drive up to Santiago where I spent a night at Casey’s house.

Casey buys some mud bugs (crawfish) from a roadside vendor. A hundred cooked up to a tiny amount of meat.

All this time I’d been in sporadic communication with my son Louie and his friends Cooper and Skyler. They were completing their epic (correct word) journey to ski in at the feet of majestic Fitz Roy and Torres del Paine — possibly the world’s most inspiring mountains. The trio turned in their “pampa mobile” rental car at Bariloche. They also ate so much steak at a Bariloche asada that they barely made it out of town. With an epic 24 hours of bus travel having scourged their minds of nearly all reason, I’m not sure how they managed to procure a rental car in Santiago, but they did. Though we later found much to our disappointment (and possible physical risk) that the 4-wheel-drive was disconnected — though the car was rented as a 4×4. (Lesson for all you aspiring travelers, never ever ever assume anything when it comes to things like car rentals in countries such as Chile. Overall the people are nice, but in some circles ripping off gringos is sport.)

Skyler, Cooper and Louie with their second rental car of their trip, this time the idea was something larger since I and Skyler’s girlfriend Karina would be crammed in there as well. The SUV was essential for slithering up the muddy and icy roads above Banos Morales, but unfortunately they got ripped off; the 4-wheel-drive didn’t engage and was a problem when things got icy.

Hint of more serious problems to come with the rental car, fuse for dashboard power connector was burned out so we did a roadside fix. Modern man has to have power.

In any case, the crew showed up at Casey’s house around lunchtime. In all my years, I’d never thought I’d be meeting my son in Chile for some skiing — amazing the twists and turns of life. After the obligatory slideshow, we crammed five people and all our luggage into the Kia Sorento and did the two hour drive up Cajon (canyon) del Maipo to the “hippy” village of Banos Morales.

Inside Cabanas Correcaminos, a $5 bottle that would cost 10 times that in the U.S., electricity from a generator, off at midnight, gas from propane cylinders.

Normally, when you’re night driving a road to a village you get a sense of location by the town’s lights. Morales is off the grid. Except for a few people running generators at night, the town goes dark as soon as the sun sets. Thus, with a good degree of uncertainty as to where we really were, we rolled into town and parked next to the only “motel” looking building with a light on. Only, where was the owner? A sign indicated we should walk down a dark street to a home.

Morales reminded me of Crested Butte in the 1960s, only without electricity. Tentatively standing at a padlocked gate guarded by a gigantic barking canine, we rang a bell rope hanging out of the wall. Sure enough, the owner of the hostel was there and arranged a deal for us at the Cabañas Correcaminos. A bit overpriced and funky, but the rooms had character. You get running water and an on-demand shower that works ok if you fine tune the flow. Just ignore the 8 inch flaps of moldy wall paper hanging from the shower ceiling like some kind of indoors lichen. As a person used to “dry cabin” living I wasn’t surprised that everything ran on small propane bottles. But when I multiplied in my head and realized that each room had two bottles inside, for a total of 12 potential bombs being used indoors within a few feet of our room, I wondered by what grace this building was still standing. Adventure travel at its best, bring your own CO detector!

In Banos Morales, looking at Cabanas Correcaminos. According to the owner various European skiers have shown up and done everything in sight at one time or another. In winter the snow comes down to town.

The key to this whole adventure is that Casey and a few other people had told us about possible road access high into the Andes from Cajon del Maipo. As it turned out a big chunk of road was kept open by a mining operation, and the crux section that continued to the alpine happened to be in the beginnings of a major water diversion project.

In the U.S., what is going on up above Cajon del Maipo and Banyos Morales would have closed the road to the public. Instead, the Chilean road crew were super nice and ran their heavy equipment from dawn till dusk to try and make the muddy quagmire passable.

Our first day of ski touring above Banos Morales: wind. I was so sick of blasting wind by this time I was thinking of just heading to Santiago and being a city tourist until my return flight. Luckily I held out and blue sky rewarded.

Truth is, I don’t think I’d ever driven that much mud for a ski touring approach. First day, temperatures were warm and we made it to highland parking with no issues other than a coating of mud that turned the silver Sorento a nice shade of brown. We did an exploratory tour into the wind then headed back down to pick up Skyler and Karina. Next morning we didn’t get so far in the car. Parts of the road were frozen; that’s when we discovered the Sorento’s 4-wheel drive did not work. But we were high enough on the road for a short approach march to take us to the goods. We even did some dirt walking, which according to Louie’s crew is essential for any true southern Chile adventure skiing.

Mud and ice were not the end of it. Rather take time out that first morning looking for a bridge (our maps didn’t show one), we opted to rock-hop across Morado Creek. The crossing looked easy at first, but more than a meter of snowpack had been smoothed by the wind to hide numerous braided and open water channels from our ground level view. It took about an hour of fooling around and some water in the boots to get across it all. So for day 2 we did the same, with even more water in the boots. (I kept thinking to myself “there has to be a bridge.” Sure enough, at the end of the day we used our brains, observed where the snowmobiles had tended to change sides in the valley, and there was the bridge.)

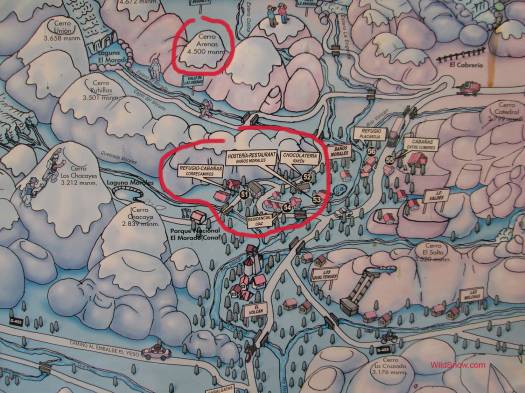

The longer approach didn’t deter the boys. The day before we’d spied a triad of beautiful couloirs on the southwest face of 4,400 meter (14,435 foot) Cerro Arenas. The slots appeared to be about 800 vertical feet, with an approach up an apron of perhaps the same. A few dozen switchbacks later it became obvious that the “short” approach to the base of the couloirs was nearly 1,500 vert.

Karina and I decided to farm out the apron and sun on some rocks below as we waited for Louie, Coop and Skyler to climb and ski the longest couloir. We figured they’d need a few hours time. We were wrong. Some time later, on the radios: “THIS THING IS HUGE!” It turned out that main couloir on Arenas has nearly 3,000 vertical feet of skiable snow. Two hours went to three, then nearly four. The thing was so big that by the time they topped out I honestly could not see them, they were so far away. Honestly, I’d never in my life been so fooled as to scale. Funny thing is, we’d known that a 19,000 foot peak (Vulcan San José) loomed in full view just over to the right (towards Argentina). That was like having Denali right there staring you in the face. Why having a gigantic monolith as a reminder didn’t give us some clue as to what we were involved in, I do not know.

As far as I was concerned, beyond getting together with Louie and his friends, the main event here was that the weather finally cleared. That second morning dawned with crisp blue sky and faint winds up high. Not a cloud appeared all day, and the next morning was nearly the same. After a long wait and a lot of running around, I finally got in a couple of days “spring” ski touring in Chile. Check out a few more photos.

A hanging valley provides up to almost 6,000 vertical of ski touring around the corner from Cerro Arenas. Karina Olson tries a few vert.

To give you some idea of the scale we were dealing with. Karina skis the hanging valley to west of Cerro Arenas. Way way down there, our rental car awaits.

The river we had to cross is the Morado. It forms a huge valley that locals snowmobile and are said to have a hut installed somewhere.

Mud, but check out where the road goes for access under Cerro Arenas.

Son Louie and I. He’s become quite the adventure traveler in a style that combines a reasonable approach to ski mountaineering along with a ‘get it done’ attitude.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.