Aaron Diamond (right) and Evan Pletcher building a refuge while getting covered in rime ice. Day 3, Sultana Ridge Mount Foraker, Alaska.

Editor’s note: With modern weather reporting, gear and climbing techniques, the time it takes to do big Alaskan peaks is shortening. But they’re still tough, and not everything will always go as planned.

The men attempting to ski the “Alaska Range Family” in one trip put it all on the line on Mount Foraker.

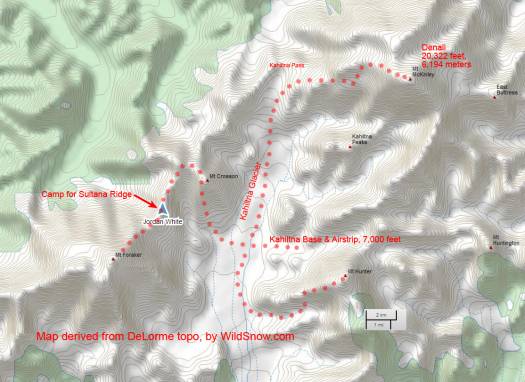

This is not a simple climb with an escape route you can reverse in terrible weather or with an injured or sick partner. Before you even begin the classic Sultana Ridge section on Foraker, you must climb 6,000 vertical feet up and over Mount Crosson (see map at bottom of post), ending up in a bivouac you have to climb UP from to go forward — or back home. Commitment is synonymous with alpinism. Here it is in spades.

(Regarding our “mother” references: As viewed from certain locations, Mount Foraker, Mount Hunter and Mount McKinley line up in a family of three which in Alaskan native languages are termed the “Mother/Sultana, Child/Begguya, Father/Denali. These naming conventions have gained traction as they’re more honoring of these peaks than monikers of corrupt or forgotten politicians, or in the case of Mount Hunter a guy’s aunt who financed his Alaska trip).

Aaron climbs the lower east slopes of Crosson. Kahiltna Glacier and Mount Hunter in the background. The boot crampon climbing here was incredibly good on the way up. Getting down on skis with a heavy pack, after the sun and wind had their way on the snow? Another story. Day 1.

Day 1 (May 15)

Morning at Kahiltna Base. We bury our food cache and march across the Kahiltna Glacier with 75-80 lb packs. For the short journey over to the base of the Crosson we opted to leave the sleds at Base. Two hours later we’re at the bottom of our next 6000 ft climb.

Our camp at 10,000 feet on Mount Crosson. We sit look at out last project and perhaps the next.

Swapping skins for spikes we boot up Crosson’s lower east slopes and after a couple hours make it to the 8000 ft camp for a break in the action. After chatting with a couple guys who were doing the climb in full-on expedition style we move onward. Our lighter loads help, but it’s a given they’ll be more comfortable in camp than us — and let’s not think about what’ll happen if a storm comes in and we run out of food.

After some grueling post holing and climbing we finally make it to our goal for the day, the 10,000 ft camp (still below Crosson’s summit, which we plan to traverse tomorrow). On the way to “10 camp” we notice that the Alaskan version of a dust storm has started to affect the snow. Black grime has blown off the ridge lines, creating icy sun cups in the snow. We set up camp, house some food and head to bed knowing that tomorrow will bring no shortage of challenge.

Leaving 10,000-foot camp on Crosson, we enjoy nice easy staircase cramponing that would later transmogrifie to the worst skiing imaginable.

Day 2 (May 16)

We eat heavy and sleep well, then it is time again to put one foot in front of the other. Just above our camp we run into some rather heinous looking, but good cramponing black ice. Past this icy section of the climb we are on snow again. At this point Crosson becomes glaciated so out come the ropes. We weave our way back and forth — up and up until we finally reach the Crosson summit. This is easily the hardest we’ve ever worked for a 12er (12,000-foot peak)!

Jordan tops out on Crosson with Denali in the background. Day 2.

While we crest the summit ridge of Crosson the wind sends bits of snow and ice flying into the air, stinging our faces. For obvious reasons (as in, not wanting to camp on top of an exposed Alaskan peak) we drop 1000 ft off the back side towards point 12,472 on the ridge leading to Sultana. The wind has its way with us for the remainder of our way to camp. We estimate it’s blowing a steady 40 mph. In this col we build a camp and wind wall with blocks quarried from the nearby slope. We cook up Thanksgiving dinner (one of our planned meals, turkey etc.), and pass out. I should re-mention that we are four dudes in a small Black Diamond Bombshelter tent — tight quarters and a lot of winter gear.

Evan looking like he is feeling the 6000 ft climb with full packs over Crosson. Day 2.

Day 3 (May 17)

The daily routine of waking up, dragging our asses out of our warm sleeping bags, making breakfast while packing and roping back up for more walking is becoming normal life at this point. Walking out of camp, we opt for the traverse across the southeast slopes of point 12,472 rather than climbing up and over. Side footed traversing with heavy packs across steep slopes like this is as awkward as being caught in a line dance that you don’t know the steps to.

Aaron finishing the traverse across point 12,472 on ridge connection Crosson with Sultana and Foraker. Looking ahead, and realizing that we still have a long way to go. Day 3.

An hour or so later we find ourselves on the other side of the traverse for a nice rest. The miles of the Sultana go on in front of us, each with their own bit of challenge, be it deeper trailbreaking, hidden crevasses, or crevasse jumps. As if that wasn’t the full experience, after a few more hours of walking the weather comes in. We haven’t made it to our goal of the 12,300 Sultana camp, but we are about an hour away. The clouds come over the ridge, the snow starts falling, and the wind is blowing everything sideways. Visibility goes to nil. Despite our best efforts it feels like being trapped on the inside of a Ping pong ball. We wait for about 15 minutes to make sure that visibility won’t return, and eventually back track about 10 minutes to where we last saw a good campsite, and get to work building a suitable platform and windbreak for weathering a storm.

Anton and Evan on the ridge approaching one of many crevasse jumps. Sultana ridge and Foraker summit up ahead. Day 3.

Building a site to stick out an Alaskan storm is no small or quick task. The weather continues to get worse and worse as we set to work building camp. We spend a couple hours cutting and stacking blocks, and digging out a level platform. By the end our walls are about chest high to surround our Bombshelter. Four dudes, all their clothes and sleeping bags inside a Black Diamond Bombshelter hiding from the elements gets a little crowded, but then you realize that it’s way too windy to cook outside, so inside the vestibule it is. Let the steam show begin. We eventually settle in and drift to sleep listening to the wind battering our tent vestibule, yet with a promising forecast for the following day from our weather ace Joel Gratz.

Jordan getting close to where we camped as the clouds look to be threatening. Day 3.

Day 4 (May 18)

We wake up early to check the weather. It is mostly clear, but the wind still blows lenticular clouds on top of Foraker indicating possibly extreme winds at higher elevations. We decide to bunk and repeat the weather check in a few hours. We wake up again at 9 and things seem to have cleared off, so we make breakfast and get on with it. About 11 we are walking out of camp. Late start, but it’s Alaska so light is no issue. We cross the last of the “flat” part of the ridge to the base of the Sultana proper. The ridge is deep post holing and route finding around the cracks in the ridge. Once to the base we start efficient crampon climbing again and we are making good time.

But the entire time we are looking behind us watching the clouds creeping up towards the ridge, and constantly battling the increasing winds. About the time we cross the 14,000 foot level, we decide to just call it an acclimatization day. We turn around without even bothering to transition to skis and walk back down the ridge to camp. The winds are a lot lower on the ridge, but looking back at the plume of snow off the top of Foraker, whatever regrets we may have had about turning around are subdued. Arriving at camp, we wasted little time heading to bed as the wind continues to increase in force.

Next day (5), more of the same. Turned out we would have one window for a summit push, day six.

Part 2 — summit and ski/snowboard descent, publication just as soon as we get it edited and assembled.

Anton and Evan approaching the bottom of the ski line on our first summit attempt. Let’s just call it an acclimatization day.

(‘Ski The Big 3 is an Alaskan ski mountaineering expedition cooked up by four deprived (or perhaps depraved?) guys who never get enough ski and snowboard mountaineering. Aaron Diamond, Evan Pletcher, Anton Sponar, Jordan White. The idea is to ski Denali, Mount Foraker, and Mount Hunter all during one expedition. They’ve got six weeks worth of food and enough camera gear to outfit a small army. Should be interesting. We wish them safe travels, we’re enjoying being their blog channel.)

Ski The Big 3 routes both done and proposed. Metrics: Kahiltna Base is at 7,000 feet elevation, Denali (Mount McKinley) tops out at 20,322 feet, 6,194 meters, Sultana (Foraker) is 17,400-foot, 5,304 meters. Derivative work based on screen grab from paid DeLorme subscription. Click to enlarge.

Jordan White is a strong alpinist who finished skiing all 54 Colorado 14,000 foot peaks in 2009. He guides, tends bar, and lives the all-around perfect life in Aspen.