Large avalanches that result in huge debris piles fascinate us. But small slides can be just as deadly.

Large avalanches look scary. They should be. Monster slides cause certain injury or death if you’re caught.

Nonetheless, an alarming number of tragedies result from small avalanches on somewhat innocent looking slopes. This is especially true in mid-continental snowpacks such as Colorado where small hair-trigger slabs can liquify in an instant, knock you down, and bury you deep enough to require a lengthy dig-out extrication while you suffocate. But the warning about diminutive avalanche slopes applies to any snow climate — especially if terrain traps such as cliffs or gullies lurk below. Here is one experience of my own with the “little ones.”

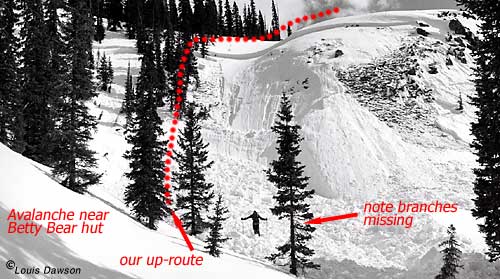

We are lounging in Betty Bear hut (Colorado’s 10th Mountain Hut System). We look south at an inviting ski slope, a little thing of perhaps 300 vertical feet, steep enough to avalanche but not an obvious slide path; no obvious demarcation such as the classic swaths you see cut into mountainsides worldwide.

There are a few signs, however. First is the shape and exposure of the slope, a northerly facing convex bulge, devoid of trees, wind-loaded with a pregnant belly of snow. The conifers at the base of the slope are not obvious avalanche trees with heavily stripped branches and scarred bark, but to the trained eye they tell a story of vegetation abuse. What I see is enough — with years of experience (including plentiful mistakes) my avalanche eyes are tuned, and the slope looks like something to avoid.

Nonetheless, I need to reach the top of the pitch to take photos of the hut. So we climb a conservative line to the left, on lower angled ground with denser trees that indicate a lower frequency of avalanche activity. About half way up we realize the snow is in bad shape for skiing, breakable crust and worse, so my companion Andrew Meeker leaves his boards stashed below the last pitch of windpack and boots the remainder of the climb.

The slope and our route. Terrain features and a few missing tree branches indicate danger, but the slope is so small...

Just after we top out, the proverbial WHUMP echos through the forest as the snowpack does a massive collapse, birthing a thick hard-slab avalanche just 20 feet below us. We watch in stunned silence as the slab liquefies, then piles up in a deep plug at the bottom of the slope — a killer for sure.

How was our route finding? Our up-track was still intact except for one small section. Where Andrew had dropped his planks, the slide had washed over our line by just a few feet and carried his skis away (Andrew was not a happy camper…).

Our score? If the slide had triggered while Andrew was messing with his skis, he might have been swept away — but then again, if he’d had the presence of mind to take two steps to the left when the slide triggered, he would have been totally safe. I couldn’t help but note that my own tracks were 100% safe. Experience or luck? I’m not sure. I’d give us a “C” for route finding and a “B” for judgment.

Most importantly, note that it was the difference of mere feet that made for one totally safe route, and another that risked death. This validates what I call “micro route finding,” an avalanche safety skill I believe is significantly more important than snow science, and much harder to learn. It is the art of using subtle terrain variations to avoid small, but nonetheless deadly slides.

You cannot gain this skill from books or classes. You learn it by being outside observing the world around you through a lens of fear and conservatism, perhaps while following a mentor who has the knack. And all the while, you’ve got to remember how easily human error enters in — that’s the lesson I learned from this skirmish in the avy jihad.

(The Forest Service avalanche advisory for the day of our adventure was “low/moderate,” but a sudden warming trend pegged the danger way past that. One of Andrew’s skis was lost till he retrieved it that summer. We didn’t need a trip to the underwear store, but Andrew’s eyes stayed wide for a few days, and I returned home humbled, resolving to do better. If anything, this is a good example of how Colorado can build good mountaineers — it’s not a forgiving environment — mistakes are costly — if you survive you learn…)

A few tips for micro route-finding and behavior on a tender snowpack

– Look for a route that chains lower angled terrain with islands of safety so you never set foot on steeper terrain.

– Load a slope with as few people as possible. Keep your party spread out, and travel in small groups.

– Use vegetation to read the slope, but don’t depend on sparse trees to anchor the snow. If conditions are touchy, only trees tight enough to make you cuss will hold snow from avalanching.

– Avoid wind loaded “pillows” and convex starting zones.

– If your route exposes you to danger, pick a line that minimizes the consequences of an avalanche (e.g., getting swept into a gully is worse than tumbling into a fanned out debris pile).

– Consider subtle variations of slope aspect. In Colorado, just a slight tilt to the west or east, rather than dead northerly, can make a route much safer. South facing slopes can be sun hammered enough to be 100 percent safe. Prevailing winds may strip areas down to the ground, making for 100% safe ascent routes.

– Learn the subtleties of wind loading (in other words, throw away the books, forget expensive and time consuming advanced certifications, just go to the backcountry and look/listen/feel.)

– If traveling in a valley during a time of high avalanche danger, remember that large slides can pound the valley floor. These events are usually unsurvivable. Use your imagination as you pick a route, and choose a line that avoids your horror fantasy.

– It bears repeating: Use ridges to reach summits. If the signs of avalanche danger are in the red zone, ski back down your ridge route (use all that skill and expensive gear you’ve acquired to make tight and precise turns on a narrow ridgeline track).

– While skiing down, avoid falling and wallowing on avalanche slopes. If you can’t ski without falling, improve your gear or technique, or dial back your expectations.

– On the way up, avoid post-holing and trenching. If such an option is necessary, spread your group out and linger in safe zones while the leader works. If possible always use over-snow equipment such as skis, a split snowboard, or large snowshoes that don’t punch a deep track. While snowshoes may work well on a track previously broken by a skier, most smaller ‘shoes will cause you to wallow in virgin winter snow. If you’re serious about winter backcountry snowboarding in Colorado, get a splitboard rather than using snowshoes.

– As I mentioned in the article above, travel with a mentor, stay behind him/ her, and think about the moves and choices he/she makes.

– Above all, if you choose to backcountry travel during times of ultra-tender snowpack, be cautious and conservative to the point of absurdity.

We have more about small avalanches:

A few illustrations of dangerous slides that looked innocent.

How does a newcomer to backcountry avalanche safety ID how far an avalanche slope can slide?

A tragic smaller slide takes a person’s life.

Commenters, your ideas?

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.