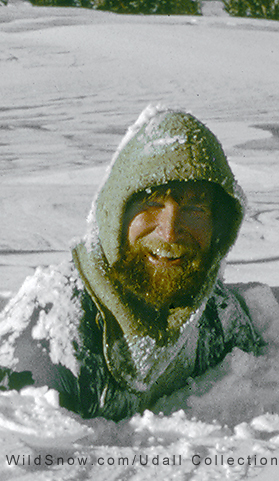

Good morning world! Randall Udall popping out of his nightly snow hole during one of his amazing California Sierra ski traverses. Click image to enlarge.

“Randall was the same age as you and me,” I said to Randall’s good friend and early days ski partner John Issacs a few days ago, “But even back in our 20s his grace and wisdom made him seem ages older in spirit.”

“Yeah,” said Izzo, “He was born with more smarts than most of us will ever have. He had a knack for seeing the reality of a situation, whether he was mountaineering or talking about environmental matters. One thing I’ll always remember is him saying something like ‘A box of Cap’n Crunch cereal has more energy in it than three times its weight of oil shale.”

(A good example of Randy’s excellent expository writing can be found here.)

Indeed, that’s Randy the environmentalist in a nutshell. His insightful take made him famous in the environmental community — in his memory much will be said and written about his contributions to conservation: his writing; his speeches; his energetic correspondence with multiple individuals.

(Editor’s note: James Randall Udall, 1951-2013, passed away several weeks ago due to aparantly natural causes near the beginning of a multi-day solo backpacking trip in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming. He was found July 3 after an exemplary wilderness search & rescue operation. More here.)

Yet the foundation of Randy the environmentalist is Randy the alpinist, the active climber, wilderness backpacker, outdoor educator — and most significantly in terms of contributing to mountain culture, creator of brutal wilderness ski traverses that lasted not hours, not days, but months. Randall’s ski treks have gone down in the history of North American backcountry skiing as feats we wilderness skiers might not care to suffer ourselves, but inspire us in our own goals both on and off the snow…

A few highlights (see below for a fairly complete list):

In 1976, Udall skied across Baffin Island for five weeks with Denny Hogan. Randy told me they encountered many polar bear tracks the size of dinner plates, and spent the whole trip “scared shitless.” Or how about 1980, when he and John Isaacs (Izzo, quoted above) spent two months skiing several hundred miles along the spine of the California Sierra!?

I got to know Randy first at a Colorado Outward Bound instructor training in 1978, then as a like minded friend in Crested Butte, Colorado when we both happened to live there in the late 1970s. Since then we continued the friendship with occasional spates of email correspondence, sometimes about local conservation controversy (which we didn’t always see eye to eye on). But more importantly in my own purview, I cherish the times Randall reverted back to his ski mountaineering mind, and dropped me pearls of wisdom about things such as modern avalanche safety procedures.

Last winter we had one of our worst Colorado avalanche accidents ever when five people died in a slide near Loveland Pass. In a few emails back and forth, Randy and I pondered things such as “is there such a thing as a ‘master’ of avalanche safety?’ And what about all the fancy gear we now have that supposedly makes us safer?

I make my living writing about that stuff. Is it not axiomatic: the more gear the better? Randall put the boot on that. His wisdom was harsh, funny and infuriatingly true:

“I’ve given it all up,” he wrote. “The only thing I carry now is a bear claw. A talisman. I’ve seen enough slides now to know that I never want to be in one. A bear claw might be better than a Pieps or whatever it is that you guys carry now. Makes you hug terrain features like your first lover.”

And Randall did hug the terrain. He learned that style back before we even had electronic avalanche beacons; when we were using incredibly high-tec devices known as “avalanche cords.” The idea was the fifty feet of string trailing behind you would enable your friends to dig you up alive. Fat chance. Better hug the safer terrain.

I didn’t have the personality for what I called Randy’s “monk” traverses, but we had mutual respect for each other’s style (I was more a ski alpinist in the European tradition of climbing mountains and skiing down.) So during Crested Butte days we joined up on occasion for various mountain endeavors; everything from working carpentry together on tract condos to being Outward Bound staff during some of the same courses.

February, avalanche danger. Randy and I are both 27 years old. We have the brilliant idea (which I’d like to blame on Randy, but that would be unfair) that instead of skiing the usual route through the Elk Mountains over Pearl Pass, dangerous enough, we’d head up Slate Creek, over Yule Pass, then down Yule Creek to the town of Marble. We make short work of it, but once in Yule Creek we realize we’ll have to pass below more than a hundred avalanche paths, many of which intersect in the bottom of the valley — not even a safe place to take a pee. We just look at each other and say something like “spread out, and keep moving!” or perhaps more accurately in the vernacular of two 20-something Colorado mountain boys “let’s get the f** out of here!”

As if that isn’t enough, neither Randy nor I know the secret of getting out of Yule Creek by climbing a few hundred vertical feet up to the Anthracite Pass trail. Instead, we blunder down the creek until we’re clinging to tree branches while hanging over a hundred foot deep gorge. Map reading? What map?

Obviously we made it — the blow came later when we were stranded in a dive bar in Marble full of pool-shooting alcoholic miners, heated by an over-fired wood stove that melted the knees off my ski pants. We’d figured that somehow we’d get a ride to Aspen. Aspen? Most of the besotted pool sharks had never heard of the place. I had to call a friend who made the three hour round trip to retrieve us, royally pissed off.

We pick the classic Pearl Pass for our return. Only we make the classic mistake of thinking another, steeper and more avalanche prone col is the correct route. Indeed: Maps? What maps?

We realized our mistake once we were about halfway up the couloir running to the col. Obviously, even a Jeep trail wouldn’t fit — and the real Pearl Pass has a road over it. Nonetheless we figure we can top the “pass” and suss out a way down the other side. In this case, all roads did lead to Rome so long as we kept Aspen behind us. Only our road is quickly becomming a major avalanche danger zone as we wallow up to our chests in fearsome Colorado sugar snow.

Aha. Terrain will save us! Randy leads up and over to a rocky rib forming the side of the gully. Soon the “terrain hugging” is lower 5th class rock climbing where a rope would be an answered prayer. Our primitive touring skis strapped to equally neanderthal backpacks flip around and try to jackknife us off the rock as we claw for footholds with our clunky ski boots. At one point, Randy shares about how well his ice coated fleece jacket grips the rock during a belly crawl, as opposed to my fancy nylon windshell. I suppose that’s something he figured out during his last 2-month cloister in the Sierra. Once over the “pass,” we are amazed when we ski frozen south facing corn snow, down a few thousand vertical feet to a valley that leads into Crested Butte.

That was the terrain hugging, but what about the people hugging? Indeed, as many will share as Randy in remembrance of Randy, the man had a huge heart.

I first met Randy during an Outward Bound instructor certification course in June of 1978. I was limping through the mountains, coming off year of healing a leg broken like a matchstick. Being there was a big deal for me, as I’d been unable to ski or climb for more than 12 months.

Looking to enhance the alpine mood of the instructor course, I slept by myself on the ice in the geometric center of an alpine lake. I was thinking this was a spiritual nexus, or at least a pleasing rack for star gazing. I did feel a buzz, probably because the lake defile turned out to be a cold air sink and I had only a summer weight sleeping bag. Thus the experience was one of spiritual shivering.

Randall and the other OB folks knew I was healing. They were not surprised to see me remain in my sleeping bag on the lake ice, waiting for the sun as they cooked breakfast. Soon the the group was tromping by my bivouac on the way to a climb. Unasked by me, and unanticipated, Randy had carried his unzipped sleeping bag bundled in his arms, and threw it over me as he walked by. This was more than 30 years ago. I still vividly remember his gesture and the warmth of that quilt draping down on top of my cryogenic nest like a big warm hand.

Another Randall connection I can share, actually two. This photo (click to enlarge) is camp at Halfmoon below the south shoulder of Mount Massive, a Colorado 14,000 foot peak. It's 1979 and I'm teaching a winter Outward Bound course. The students are on solo, so I'm taking a break and figured I'd ski Mt. Massive (which later turned out to be one of the early 14er descents that began my project to ski all 54 of them; there was just enough snow on the actual peak to ski from the top). Randy knew I was up there by myself, and showed up that evening and spent the night. The next day we climbed the peak together. Randy downclimbed while I skied (he was never a skier of the steeps). Thinking back on the occasion, I'm pretty sure Randy didn't want me up there doing mid-winter ski mountaineering by myself -- which yes, is definitely pushing the limit of what's socially acceptable in terms of risk taking. But more, Randy just knew that it would be better overall if he was there as an alpinist friend. See the dog in the photo? That's Princess, my husky companion at the time. Later, when Princess was killed by a car, Randy helped me bury her. Another precious memory of the big man with the big heart.

Sixty-one years old is too young to die when you’re active and healthy. In that sense Randy’s passing has been a much bigger blow than if we contemporaries of his were all in our 80s or 90s, looking at each other and thinking “your turn next?”

It helps to know Randy’s life was well lived, and his way of death so final and beautiful (he laid down on the trail and passed with his trekking poles still strapped to his hands), that after the grief you can’t help but feel a warm glow. Yes, in this world of violence against both man and nature, it is possible to live a noble, loving life.

Some of Randy’s wonderful ski treks:

– 1975, three weeks from Crested Butte to Steamboat Springs, Colorado, with Bill Frame, Jerry Roberts and Dave Ranney

– 1976, Baffin Island with Denny Hogan 5 weeks, 200 miles from Broughton Island to Pangnirtung on Baffin Island. They encounter polar bear

tracks the size of dinner plates, and spend the whole trip “scared shitless,” said Udall.

– 1977, Colorado, Silverton to Monarch Pass, then to Crested Butte with Jerry Roberts, Frank Coffee (possibly Mark Udall).

– 1978, Wyoming, Wind River Mountains, late February ski traverse taking the complete mountain range south to north, from South Pass to Dubois, three

weeks, approximately 200 miles, with Mark Udall (now U.S. Senator) and John Isaacs

– 1979, California Sierra, John Muir Trail 230 miles. Four weeks in February. Randy skis with Brad Udall and Craig Grossman, Barb Eastman (Barb exited early to return to work, Brad exited after three weeks because of frostbite). Yosemite to Mount Whitney.

– 1980, California Sierra, two months with John Isaacs, Sonora Pass to Mount Whitney, Jan 4 to March 23 (year verified by Isaacs)

– 1981, California Sierra, Muir Trail on nordic racing gear with Brad Udall, 7 1/2 days

– 1983, Utah, March ski traverse of Uinta Mountains with Day DeLaHunt and Ben Dobbin

– 1993, Colorado, Denny Hogan and Randy ski the high line traverse from Silverton to Wolf Creek Colorado, 5 days, 80 miles

John Isaacs also related that at some point in the 1980’s Randall did a ski traverse of the Uinta Mountains in Utah with De DeLahunt. He also skied from Crested Butte to Silverton, date unknown, so that he had eventually skied the entire length of Colorado with the exception of some sagebrush to the North and desert to the South. Through the years he continued to do ski trips into the Sierras with Craig Grossman, Auden Schendler, daughter Tarn and other friends.

Randall’s ski partner Craig Grossman sent this in, condensed from his email:

“1979 We did the John Muir trail in February. It took the whole month, three caches. It was with Barb Eastman (she went out at Mammoth to get back to work) and with Brad, Randy’s brother, who had to go out with frostbite after 2-3 weeks. We were living out of Randy’s favorite snow cave design, parallel tunnels with food passing holes between, doors blocked in. Dug quickly with cut off grain shovels.The last Sierra tour we did was in the Spring of 2011, Bishop Pass to Taboose Pass, high along the Western side of the Palisades. We had perfect weather and snow. It is a wonderful tour. We had hoped to do a similar 2012 trip but as you know snow conditions were minimal. Randy had moved up from his more comfortable leather boots to an old pair of Scarpa T3s he had cut up for weight reduction. He was on relatively narrow tele skis.

In the 90’s there was a base camp trip over Piute Pass and the Humphrey basin area and in the early 2000’s a short tour in the Broken Top area out of Bend Oregon and a short trip on Shasta. There were also 2 or 3 times in late March when I had gone into Tuolumne Meadows with my brother and Randy would hook up with us for a couple of days as he came through exploring on his own from the Yosemite or the East side and returning on the same. He loved to search maps and come up with new and varied route connections. His knowledge of the Sierras was incredible, especially for someone who did not live near there. It was amazing to hear him chat with locals and with some of the guides we ran into. He was so quick at processing their information along with what he already knew to come up with new possibilities. His mind along with his spirit was amazing.

Most of Randall’s ski traverses are or will be included in the WildSnow Chronology.

Randall’s backcountry companions over the years, feel free to comment with stories from your trips.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.