One of eleven individuals whose demise in an airplane crash inspired Friends Hut. Michael Pokress backcountry skiing in Maroon Bowl, Aspen, circa 1979. Click image to enlarge. Photographer Michael Kennedy contributed numerous images for fundraising graphics during the funding period for the project.

Year, 1991. Our corporate board meeting was an important occasion. Stately englemann spruce formed the walls of our boardroom, a deep autumn sky vaulted the ceiling. Colorado alpine air fed our lungs. Business problems were discussed; motions argued and voted. Revenues looked good, our business goals were being met.

As a sizzling campfire warmed our toes we stood together in a circle of remembrance.

In turn, we spoke of our friends who’d died nearby eleven years ago. The friends whom we’d laughed with, partied with, climbed with, skied with, cried with, rejoiced in life with. Next to us, the hut we’d built to remember them warmed our hearts. Having the Friends Hut would never replace those fine individuals, but what stronger way to make them live on in the hearts of their friends and loved ones?

Friends Hut circa 1985, that's founder Graeme Means over on the left. A bevy of founder babes as well. Not sure which ones were our wives then, but Graeme and I are still married to those same mountain girls.

1980, June 18. Place: Crested Butte, Colorado. That morning, in the mundane setting of the local gas station, I’d seen my friends Robert “Pimmy” Pimentel, and Michael and Ellen Pokress. Pimmy’s hobby was mountain flying, and he was driving the group to the airport for a quick hop over the mountains to Aspen. At about the same time, another airplane was preparing to take off from Aspen — headed for Crested Butte.

That same afternoon. Gut punch.

I was enjoying the sun on the back porch of my mother’s house, when loud exclamations and weeping broke into my daydream. News of the worst kind had come. The planes from Crested Butte and Aspen had taken a low route over East Maroon Pass, probably to sight-see or save time and fuel. At a relative velocity of at least 400 mph, in a part of a second too fleet for any pilot’s reactions, they collided. Everyone was dead, a total of eleven people including Ellen’s unborn child.

My grief was physical, like a 500 pound lead ingot strapped to my neck. In a blank state of shock I sat behind the house and stared at Coal Creek for two hours. My brother Tapley showed up. As hysterical men of action, we concluded that we should go to the crash site. I grabbed my ski mountaineering gear, he kick-started his enduro bike, and riding double we motorcycled up the jeep trail to snowline on East Maroon Pass.

Stumbling up the slushy corn-snow of a Colorado spring afternoon, Tapley and I arrived at the wreckage of the Aspen plane (Pimentel’s was farther north, down the valley). The rescue people had posted a guard, so we took up an eerie vigil in a grove of scraggy timberline pines. Pimmy’s plane had fallen farther away, and a semblance of sanity kept us from that abattoir. After a few hours the helicopters left with the guard, the shadows lengthened, and we steeped over scraps of metal and human bone to view a crushed object resembling the result of a junkyard car compactor. That was all the evidence we needed. Any shred of disbelief was shattered.

The need for remembrance, for memorial, made our scalps tingle like static from a mountain thundercloud. What to do? These were mountain people, many of them skiers, some climbers.

So Tapley and I hiked to the top of a nearby slope, and as the corn firmed up under the raking light of sunset, I clicked my bindings. My brother had no skis, so he wrapped his arms around my waist and stomped his motorcycle boots onto my ski tails. Our first turn failed, but he climbed back on and we hit a rhythm. “Here’s one for you Pimmy,” we shouted on one curve, “For you Michael,” on another, “For all you people in this crash,” we yelled in unison as we cast a comb of corn crystals. Turns were our prayers for the dear mountain friends we had lost.

The people who died on East Maroon Pass that day were all part of a huge social circle that took in Aspen, Crested Butte, and points beyond. The numerous memorial services and wakes were almost too much. Not only was the loss of numerous friends so immensely powerful; but it was the close of an era. At least several people on those airplanes were heavily involved in the ’70s party culture, and some informal wakes seemed a last hurrah to those ebullient yet frequently self-destructive times.

Later, people noticed that through grief they’d grown closer to each other. Former strangers had become acquaintances, if not good friends. Talk turned to memorials. Someone placed the bent propeller of Pimmy’s plane on a sublime promontory near the accident scene. At his funeral, while classical violin music wafted over columbines and lupine, we reached into a box and cast handfuls of Pimmy’s ashes to his favorite trout water.

None of this was enough. We needed a living remembrance.

At this time in Colorado the Tenth Mountain Trail hut system was still a baby, but obviously the coming thing. Near the crash site, the Fred Braun Memorial Hut System operated several well established huts. Both systems were built in memorial to deceased loved ones. For mountain folks looking to remember the crash victims, building another such hut was the obvious act.

Talk is cheap. Yet the energy and commitment of the victim’s friends and families was incredible. Soon after the accident a memorial fund was set up in a local bank. Donations flowed in unexpected volume, and fund raising made up the rest. In June of 1980 the account had $660.00, by the time construction began in August of 1984, it topped at $40,000.00.

The first hut committee meeting was an informal affair: mostly friends of Robert Pimentel and Michael and Ellen Pokress. We held the gathering at the Durant barn, a huge mine shack that was band-aided into the most classic ski-bum haven most people have never seen (it’s now gone and replaced by the usual Aspen trophy homes.) Michael Pokress had made “The Barn” his home while he staked his substantial claim in Aspen, going from ski bum to real estate entrepreneur in twelve colorful years. Our meeting was held in his former room; his spirit a tangible presence.

In Aspen style, excellent wine and food were plentiful. Banter about friends past was punctuated by serious discussion of backcountry hut philosophy, design and location. Although most decisions were tabled, we agreed we’d build in the East Maroon Pass area (later to shift to Pearl Pass, due to legal Wilderness and other concerns), that the hut would be a trendsetter in design and location, and would cater to experienced ski mountaineers. Our committee included architects, building contractors, and experienced carpenters. A local attorney (the late Tom Crumpacker) was there, he would later pro-bono set up a non profit corporation. The hut seemed our destiny.

The towns of Crested Butte and Aspen are roughly 30 miles apart as the crow flies, with three popular ski tour routes (each about 20 miles), that connect the towns: Pearl Pass, East Maroon Pass (where crash occurred), and Conundrum Pass.

East Maroon Pass is a popular backcountry route, while Conundrum Pass, though longer and a bit more difficult, has the attraction of a natural hot spring at timberline. Pearl Pass is the trade route between the two areas, used since the late 1800’s by miners and mail carriers. Both east Maroon Pass and Conundrum Pass are in legal wilderness, while Pearl Pass lies on multi-use forest Service public Land, thus the obvious choice for a hut location.

People made regular winter crossings of Pearl Pass in the mining days of the forties, some on skis. But the tradition of using Pearl Pass as a recreational ski tour probably began with the cross-country ski racing team at Western State College of Gunnison, about 35 miles down the valley from Crested Butte. Sven Wick led his first group from the college over the pass in the 1950s. Since then the route has become quite popular. Before the Friends Hut, the Pearl Pass route was supported by several huts low on the Aspen side of the pass. Without other huts it was a long 18 mile tour from the huts on the Aspen side, over Pearl Pass, then down to a trailhead near Crested Butte. To serve backcountry skiers, a hut on the Crested Butte side of the pass was the obvious need.

During summer of 1981 I joined ten people from Crested Butte and Aspen to survey possible sites for a hut. The undercurrent in the group, comprised of numerous ex ski hippies whose trucks sported bumper stickers such as “question authority,” was to bypass the U.S. Forest Service special use permit by finding a parcel of private land in the right location.

We found a patented mining claim at timberline on the south end of Carbonate Hill, (the ridge that divides East Brush Creek from West Brush Creek, on the Crested Butte side of Pearl Pass). Our idealistic vision was a European style high altitude cabin. We chatted about one hut in the Alps where, when you felt the call of nature, you could look down 3,000 vertical feet through the hole in the outhouse. That sounded just about right.

Our proposed site was not not perched on a cliff, but it went beyond any other hut in Colorado by being above timberline on an exposed ridge. We got a 30 year lease on the claim. But it was soon clear that such a hut was too far from what America’s ski touring public was used to. More, approval by building authorities in the ranch town of Gunnison would have required a miracle.

So much for idealism. Going back to public land, we found a possible site at timberline on the Crested Butte side of Pearl Pass, and applied for a special use permit from the US Forest Service.

The Taylor River Ranger District denied our permit. In their initial letter of refusal they gave their reason for as “this proposal is inconsistent with current National Forest Management direction, it has been denied”. Later, we found out their main concern was the hut not having a backup management plan in the event the supporting corporation went defunct. (Ridiculous on the face of it, but remember this was the dark ages in terms of backcountry ski huts in Colorado.)

In favor of grazing cattle and the occasional hunting camp, The government ‘crats had dashed our hopes like a falling widow-maker. I wept. A committee meeting was called, and the members, with typical optimism, decided to find out the exact Forest Services objections, then to address each of these concerns and resubmit the application. The late Jim Gebhart took the reigns on that one, since he was located in Crested Butte and involved in local land use as a realtor and recreator.

We lacked credibility. I remember one conversation with the late Greg Mace, a well respected local outdoorsman and rescue volunteer. He was under the impression the the hut committee had spent all of the memorial fund and that we were penniless. And he told me in private that he figured anyone from Crested Butte was a derelict pothead! Indeed, at the time Crested Butte was the Gunnison County version of Haight-Ashbury, but the hut committee was doing a fine, well organized job.

As it turned out, what the Forest Service wanted, and what would give us more credibility, was incorporation. This was ironic for us because incorporation absolves individuals from a great degree of ultimate responsibility. In hindsight, however, incorporation as a not-for-profit is the most important thing we did to get the Friends Hut built. The hut committee met in August of 1982 to incorporate. We refilled the permit application in 1983, and approval followed soon after.

After obligatory celebrations, we began the arduous process of raising the balance of funds needed for construction. Non-profit fund raising is an art, and we learned the hard way why many big foundations contract it out. Our most successful effort was a raffle—grand prize a heli ski holiday—won by a non-skiing Texan. Our most discouraging incident was when extreme skier Sylvain Saudan came to town. On short notice we put together a fund raiser that featured his movie about skiing 8,000 meter Hidden Peak. Ten minutes before curtain time, with a full house, he doubled the amount of money he wanted. We barely broke even on that one.

For one of our more cutting edge fund raisers we brought the then somewhat avant garde rock industry satire 'This is Spinal Tap' to Aspen Town. As far as Friends Hut, yes my friends, it _does_ go to 11!

In fall of 1983 the howl of chainsaws marked the start of construction in the alpine forest below Pearl Pass. Over an eight week period we created a 20,000 dollar helicopter bill and an enclosed hut, not quite ready for the public, but useable nonetheless.

Friends Hut founders Jim Gebhart and Robin Ferguson goofing around during outhouse improvements at Friends Hut in 1987. Note how the outhouse is located on pedestal, to reduce snow shoveling due to extreme snow depth at this altitude. Gebhart died in 2005, Robin passed away in 2007.

Picture a small hand-crafted log cabin with a high peaked roof—comfortable for nine or ten people—but cozy and efficient. Now, think of a pristine mountain bowl, extending from timberline at 11,500 up to the summit of 13,521 foot Star Peak. Combine the above and you’ve got the Friends Hut.

Inside, you’ll find an efficient kitchen complete with a propane stove (as with many Friends Hut amenities such as solar, having a propane stove in a Colorado mountain hut was considered cutting edge at the time). The wood stove stands in the middle of the common room, bordered on one side by couches that double as beds, and on the other side by a beautiful hand crafted trestle table. An indoor wood supply and sleeping loft complete the picture.

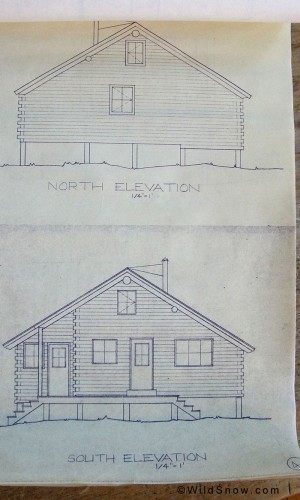

Original Friends Hut elevations, drawn by charter board member and architect Graeme Means. Design was done by group input, with principles being Robin Ferguson, Kendall Williams and Means. Click image to enlarge.

Amazingly, we’d built the Friends Hut with almost all volunteer labor.That’s nothing less than a miracle considering most huts in Colorado are now built by contractors at costs exceeding $100,000, with some “huts” costing several times that! That winter (1984-85) we experimented with different kitchen designs and sleeping arrangements. The next summer was a time for minor improvements. And as the first snows flew in November of 1985, we erected a custom outhouse, complete with picture window. After inspection and testing, the toilet facilities were approved by backcountry skiers with world-wide experience, and we officially opened for business.

Since that first season now decades ago, Friends Hut has been consistently popular and blessed thousands of backcountry skiers with a fine experience. With the hut in a roadless area, all the supplies are horse-packed, backpacked, or helicoptered in. Most of the work is done by members of the “working board,” strictly as volunteers.

It’s now many years since the East Maroon plane crash. In those years the Friends Hut has achieved a reputation as one of Colorado’s most innovative huts, one of the hardest to ski to, and one of the best for ski alpinism. It was the first public hut with photovoltaic lighting, the first with gas cooking, the first with a rescue radio, and the first with a two story picture window privvy. It also may be the hardest Colorado hut to get to. And that’s good.

Many Colorado huts are located in the timber close to nearby roads, some on snowmobile tracks. You won’t remember the slog to those cabins. Ski to the Friends hut over Pearl Pass, and you’ll never forget it. You’ll remember dealing with the short avalanche slopes below the pass. You dialed your stability evaluation, traveled one at a time, checked your beepers, and mastered the challenge. At the top of the pass a gnawing wind iced your mouth to a grimace, but the stunning vista of the Elk Mountains drove a smile that no ice could hide. The glow of success kept you warm. You lucked out, ten inches of powder blanketed the route down to the hut, and once at the hut you can look up the hill and see the figure-eights you made with your friend. At the hut, you spent three days skiing the numerous 13,000-foot peaks that surround the cirque like diamonds in a queen’s tiara.

Nowadays, Robert Pimentel’s mountaineering parka hangs on the wall of the Friends Hut, with his name written in bold lettering. If you sit by yourself in the dining area, gazing at the majestic spruce and wind hewn peaks, you get the feeling that Pimmy, along with the other fine people who perished in that infamous accident, is out there fishing or climbing. You expect him to walk through the door any minute to get the parka he forgot. I plan on being there when he does.

Friends backcountry skiing hut trip planner.

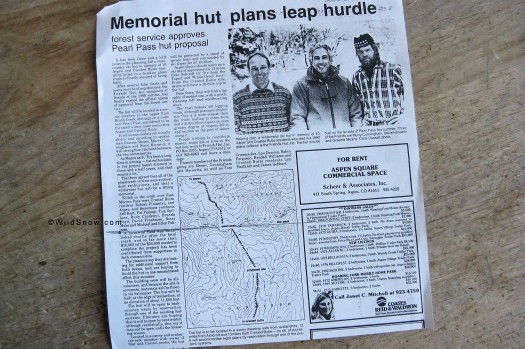

From Aspen Times, June 1980:

Nine Aspen area residents were among the 10 persons killed in two plane crashes near the summit of East Maroon Pass.The two privately owned planes, a six-passenger Cessna 310 and a four-passenger Cessna 182, were found by a search plane sent out from Sardy Field to find the Cessna 182. The six aboard the Cessna 310 were returning from a birthday party in Crested Butte given for one of the plane’s passengers, Brenda Boyd. The party was held at a restaurant belonging to another passenger, Michael Pokress.

The Cessna 182 had left Sardy Field at 11:10 am bound for Gunnison and was found 50 feet from the summit of the 11,820 foot pass.

Aboard the Cessna 182 bound for Gunnison were pilot Jeff Kest, Pat Palangi, Tom Spillane and Rudy Csadenyi.

Aboard the Cessna 310 bound for Aspen were pilot Bob Pimentel of Crested Butte, Brenda Boyd, Michael Pokress, Ellen Pokress (with unborn child), Betsy Hube and David Freedman.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.