Billy Madsen

Editor’s note: Aspen, Colorado backcountry skiers John Gloor and Billy Madsen set out for Hayden peak with safety as a priority. Then they got avalanched, big, while digging a snow pit. This event happened back in 2004. It’s a good story and we had it buried in our non-blog archives — a good candidate for our encore project, wherein we’re bringing some of those older articles up to be blog posts. Thanks goes again to Madsen and Gloor for sharing, I’m sure they’ve already saved some lives by doing so.

April, 4:00 am: John Gloor and I had planned to climb and backcountry ski the East face of Hunter Mountain, a remote peak near Aspen, Colorado. Our goals were quickly modified. New snow had fallen and continued to fall as we sat and waited for Eric, the third member of our party. At 5:30 am it was still snowing and Eric had obviously missed his alarm. Since we got out of bed at 3:00 am and our lunches were packed, we decided to make a quick trip up Hayden Peak, the most popular ski touring peak near Aspen.

The weather was still shaky, but we laughed and said, “Hey, it’s just Hayden.” We set off into the dark with light snow falling. Crossing Castle Creek on a slippery snow-covered log, in the dark, without getting our feet wet was the first test of the day. With my skis over my shoulder and my headlamp piercing the surface of the cold green water I gingerly moved onto the log. I slowly shuffled my feet until I reached the middle of the stream. Suddenly my foot slipped and my knee slammed into the frozen log. I was instantly standing in knee-deep water and my skis and poles were being swept down stream. I scrambled out of the water and John ran along the bank chasing my equipment.

Mount Hayden detail, Stammberger Face center left.

I was frustrated and cold, with water filled boots and wet climbing skins — but I was even more determined to press on. Had I known that in three and half hours I would be buried in an avalanche I would have swallowed my pride, apologized to John, walked back to the car to pour the water out of my boots, and returned home before my family awoke. As it was, I quickly squeezed the water out my socks, collected my skis and poles from the river, rebooted and started backcountry skiing into the dark forest above. (The 2,000 vertical foot approach to Hayden might be described as interesting by some, but most people would simply call it a beating with just enough return on investment to make it worth doing. The route climbs up through tight trees and gullies — tough terrain for headlamp travel, and torture during the ski-out.)

John and I reached timberline by daylight, and stood on the summit about three hours later. The sun continued to play peek-a-boo with the clouds as we stripped our climbing skins, put on dry gloves and jackets and prepared to ski. We jumped on the cornice that overlooks the main Hayden bowl but we couldn’t get the snow to slide more than a few feet. The wind had blown hard the previous day, but the upper summit of Hayden is less than 30 degrees so we were not overly concerned. Ski Hayden rarely slides and wind slab on the summit was nothing we had not seen before so we decided to wait a few minutes for the sun to pop out before we took full advantage of the dry light boot-top powder. I skied first and linked seemingly effortless turns down the face. John waited until I finished my run before he started to backcountry ski, and when he finished his last turn he had a huge grin on his face. He reached out to give me a high five and we stood looking at our tracks for a few minutes with total satisfaction, nodding our heads and laughing.

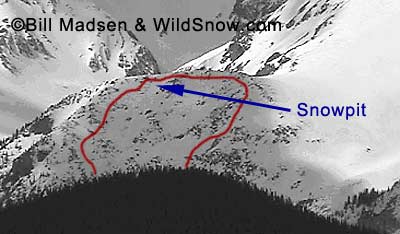

As much as John and I enjoy backcountry skiing, we are also students of our environment. As many here who read WildSnow.com, we are always seeking more knowledge about the surroundings that brings us so much enjoyment. We had been watching the avalanche reports and we knew the North and the Northwest facing exposures were not experiencing the freeze and thaw cycle that is common in late April, but we wanted to see what was happening with the snow. To that end, we decided to traverse over to a pitch called the Stammberger Face. John and I had skied the Stammberger many times, but we did not intend to ski the face on this day. Our intent was to assess the snowpack and see how the northerly exposures were progressing with the spring compaction, then hike the few steps back from the top of the Stammberger to the standard route, and ski down the way we’d climbed up.

For our pit study, we selected a section of snow that was about 30 feet from the top of the Stammberger main pitch. John dug the pit while I spotted him from a safe zone at the top. He made quick work of the hole and after a quick analysis of the snow he yelled up to me, “You want to take a look?” I slid down to the pit, which was about four feet deep. There were two distinct layers at depths of six inches and fourteen inches below the surface. The new snow was about six inches deep and it sat on a crust that failed with eight taps on the shovel. The layer at fourteen inches failed with a light tug on the shovel handle. Below that was about two and half feet of depth hoar or granular snow that looks like sugar but can act like ball bearings.

After completing our tests we realized the snowpack was very weak and that, as we’d guessed, skiing the face was not an option. I took my skis off to climb back up to the ridge and John moved skier’s left where the snow was only about two feet deep. We were less than fifteen meters apart when suddenly the entire face settled, creating an eerie hollow sounding “whoomph” that makes your heart leap to your throat. We’d hardly registered the sound when the snow fractured above us. John began to scrabble, jump and hop to avoid the sliding snow, but two huge blocks of snow rolled over him.

Unfortunately for me, I was standing in chest deep snow and the fracture propagated about 10 feet above me. Like a child being sucked out to sea with the tide I was helplessly pulled down the slope. I sank immediately as if I were in quick sand and dropped into the gut of the avalanche. The avalanche was a climax side so all the snow on the entire face moved at one time, trapping me in a huge 60 mph cloud of snow and air. I was tumbling within the belly of the beast as thoughts of my young children and my wife began to fly through my mind. Snow filled my mouth and I distinctly remember thinking,….is this it…….is this how I’m going to die………..?

The Stammberger averages about 45 degrees, and rises about 800 vertical feet with many rock bands and cliffs. It felt as if I had been pummeled by a huge ocean wave as I was ripped over the cliffs and down the steeps, tossed and turned in every direction and bodily contortion imaginable. Suddenly the turbulence slowed and I could feel myself flying through the air as I few off a cliff surrounded by thousands of pounds of snow. I landed heavily on my left side and instantly felt my left shoulder dislocate. Feebly I tried to swim with the slide to stay near the surface, and forced myself to spit the snow out of my mouth to keep my airway clear. As soon as I would spit, my mouth would again fill with snow forcing me to repeat the process. My dislocated shoulder only allowed me to do a weak dog paddle as I tumbled like ragdoll, but I knew that I had to try to swim. When I felt the slide begin to slow I tried to get my hands in front of my mouth to create an air pocket, but like a fool I had not removed the pole straps from my wrists and now my poles were acting like anchors pulling my hands deeper into the snowpack (WildSnowers, take note!). My goggles were ripped off my face, but my hood and the collar of my jacket created a small air space between my face and the snow as I arched towards the surface when the snow began to slow.

When my world came to a stop I was buried in the slide’s concrete embrace, but a strange calmness flowed through me. I did not panic or thrash about burning precious oxygen; I lay peacefully under the snow content that I had a small air space to breath. I did not think about the many avalanche victims that die from asphyxiation when an ice mask slowly forms over the buried victim’s face each time their exhalation freezes to their face. I could breath, but I was trapped. I could barley wiggle my fingertips, and with the pole straps around my wrists, there was no chance of digging myself out.

Above me, at the top of the face, John had somehow ducked under the two large blocks that rolled over him and hung on for dear life. Now he was stuck at the top of the pitch looking down at rocks, cliff bands and a huge cloud of snow in the valley that was quickly settling onto a massive debris pile. The Stammberger Face is a pretty imposing pitch when it is covered with snow, but to negotiate this terrain under these circumstances took a very calm soul. John quickly began descending the pitch but soon found himself skidding on his side across slippery rocks. He slide to a stop on top of a cliff and yelled my name. He did not hear a reply so without hesitation he hucked his carcass off the cliff. Landing forcefully on a rock shelf one ski instantly shot off his foot as slide through broken snow and rocks. He quickly gathered his equipment and began to scan the debris pile for any sign of life. The scene looked tragic as broken trees, rocks and huge piles of snow filled his vision. He pushed aside the thoughts of my wife and my kids and what he would tell them, and he began to look for any sign of me. The deposition pile was so large he knew it would be a tall task to use his transceiver to traverse the mountain of snow to locate me before time expired. John yelled my name into the quite mountain air, “Bill!!!!!!” In the deathly quite of my encapsulated tomb I could hear his call. I yelled back creating a quite and muffled noise, “john……” As John continued to descend the face he found a ski that he hoped was attached to me. He immediately realized it was not my ski so yelled my name again, “Bill!!!!!!!”

When I heard John yelling I immediately thought that he was hurt or buried. I lay there thinking. ‘Okay, I’m not dead, I’m definitely hurt, but I’m breathing. John is alive too because I can hear him yelling so all is not lost. How long would it be before someone comes looking for us?

John yelled again, “BILL!!!!!!!!!!” Again I yelled back, “john……..” At first John thought he had heard his own echo, so he called my name again, BILL!!!!!! I yelled back, “John, are you buried!” John moved in the direction of the noise he thought he’d heard. The tip of my hood had broken the surface of the snow and I could feel John’s edges grip my hood as he threw his skis sideways as he skidded to a stop on top of me. He leaned down and spoke my name softly fearing the worst, “Bill?”

“Get me out of here” I yelled and John ripped his shovel out of his pack and started digging like a man possessed. He promptly removed all the snow that was on top of me but still I could not move. I was so compressed into the snow that John had to remove the snow that surrounded me and some of the snow that was under me before I could actually move.

I gingerly began to move as John helped me to a standing position. I instantly began to shake with shock and mild hypothermia. I turned to look at where I had just come from and the enormity of the situation began to settle in. Seeing the size of the deposition pile and the fact that the avalanche had gone across the flat runout zone in into the trees made me realize how lucky I truly was. If I had hit my head and lost consciousness, or had I been hit by a tree or a rock that was also caught in the avalanche, the situation would be have been much different. I have spent a large portion of my life skiing and snowboarding in the backcountry and this was the largest slide I had ever witnessed — and I’d been in it! If I would have observed this avalanche from a distance, or if I had come across the debris pile on my way up Hayden, it would have been easy to assume that a person could not have survived an encounter with such a slide.

I took a few deep breaths and the reality of getting off the mountain rapidly began to settle in. My shoulder was badly dislocated, my left knee MCL was completely torn and my left ankle felt mangled. My right hip had been contorted and twisted in so many directions that I could not lift my right foot. The thought of skiing 2,000 vertical feet through tight trees was daunting, but the alternatives seemed much worse. Perhaps I could wait for Mountain Rescue to arrive with a sled or wait for an air evacuation? But a wait like that could be dangerous. What if the weather came in, or I had injuries that would worsen later? I was not convinced that I could ski, but John felt otherwise and quickly adjusted the binding on his skis to fit my boots. His plan was to walk, post hole actually, his way off the mountain and down to the river while I skied on his skis. The thought of John walking off Hayden made me feel sick, but I was not in a position to argue. John put me into his skis and I feebly began to work my way through the debris field. Traversing avalanche debris is very difficult when a skier is strong and it was almost impossible with my broken, twisted body. Every move I made sent jolts of pain through my body. I had made it about 50’ feet when I ran into one of my skis. When I looked back to yell to John that I had found one of my skis, I saw the tip of my other ski about 20 feet from where I had been buried. John scrambled over the debris to the ski and calmly said, “Hey, things are looking up!”

I could feel John’s spirit lift as he put me into my skis. John knew that walking off Hayden in snow that was quickly warming under the spring sun would be miserable and dangerous. At least we were both on skis and John could go ahead and find the easiest path down. Regrettably there is no really easy path off the mountain, but we did our best to keep moving. The only position that did not send jolts of pain through my body was to bend over and hang my dislocated shoulder below me. The inside of my left knee was very unstable and the outside of my left ankle could not bear weight, but somehow I managed to stand on the leg and establish a feeble snowplow position. My right hip had absolutely no strength so kick turns or quick movements were not among the tools I could utilize. My right knee and ankle were in good shape, relatively speaking, so I was dependant on these two joints to get me off the mountain. I used one of John’s poles as a crutch and a break to help control my speed, but this was a difficult task indeed. The thought of picking up too much speed and crashing kept me on my feet. However, there were many times that I thought that a fall might somehow force my shoulder back into the socket. The pain was immense and my legs were unstable but I had to keep moving. My heart was pounding and I was breathing harder than when we had ascended the mountain. John kept telling me to stop and rest, but I was afraid to stop. I was completely focused on the task at hand and I would not allow myself to be distracted. John repeatedly asked me to stop and rest but I was frustrated by my slow progress. I told John that we could make faster progress if he would simply drag me by my hair.

Finally John insisted that I stop and drink some tea, which I did. As soon as the tea touched my lips I knew it was a good decision, and it provided me valuable energy for the remainder of the decent. I tried to lock my legs in one position and dangle my gimpy arm below me but if you have ever skied tight trees you know maintaining one position is next to impossible. Every move was excruciatingly painful, but the thought of getting to the hospital and having my shoulder put back in place kept me focused and moving.

When we ran out of snow and were forced to walk, I had to develop a new technique. Walking was far more difficult and slower than backcountry skiing. I could only make small side steps using my pole as a crutch. There were times when we had to cross small sections of snow, and when my feet would break through the surface of the snow. The pain was nearly unbearable. I didn’t have the strength to catch myself from falling so I had to put an arm over John’s shoulder when the snow would not support my weight. Stepping over fallen trees seemed like an insurmountable task so I would again rely on John to lift me over each log. After two hours we had made it to the river, but there was no way I was going to attempt to cross the log that had already bucked me off during the morning trek. Again, I put an arm over John’s shoulder and we slowly walked into the water. The rushing water pulled on my legs and the pain was immeasurable. Taking very small steps John drug me through the river. Then it was just a matter of ascending an old road cut to the paved road before John could put me in his truck and take me to the hospital.

Thankfully the emergency room staff at the Aspen Valley Hospital is well trained and they immediately began to access my injuries. I had sustained a great deal of trauma but amazingly I had no internal injuries and no broken bones. I was released from the hospital and John took me home, deposited me on the couch and began to fill bags with ice to apply to each of my damaged appendages. Ironically I was soon buried in ice again to reduce the swelling from the damage caused by sliding snow and ice.

Deborah arrived home soon after John left and I gave her a stripped down version of the day’s events. Needless to say she was relieved that I had survived, but she also wanted to know what I had learned from the experience. She did not intend to be patronizing, after all, she knew whom she was getting involved with long before we were married. She wanted to know what I had “learned.”

I thought for a few seconds and said, “If you fall in the creek within 500 yards of the car, it is an omen. Turn around and go home.”

“Okay’, she said, “What else?”

This time I thought in silence for a while before I spoke. “It will be impossible for me to remove this experience from my memory. It would be ridiculous for me to believe that I could enter the backcountry without some level of apprehension. This incident has been etched on my cortex for eternity and it will make me much more cautious in the future. When I dig a pit from this point forward I will always set a snow anchor and use a rope to repel to a position before digging a snowpit. If I had been anchored, I would have been held in place as the snow slide away.”

Deborah looked into my eyes and said, “Did you think about your family?”

This time I didn’t need time to think before I spoke. “My first thought when I was pulled under the snow by the avalanche was of my family. When I was tumbling under the snow I thought about you and the kids. When I was lying under the snow and realized I was stuck but I had plenty of air to breath, I knew I would somehow get out of the snow and get off the mountain. I never allowed any doubt to enter my mind. My children have always been the most rewarding and cherished part of my life and I have no intention of missing their upbringing. I realized that I have a huge responsibility to my family, and my family must come before my ambitions to backcountry ski and snowboard big mountain peaks. I can not tell you that I will stop backcountry skiing, but this experience has and will continue to change me, and it will change the way I approach the mountains.”

Tears of joy, sadness, worry and fright filled Deb’s eyes. “Thank you” was all she said.

(WildSnow.com guest blogger Billy Madsen is the Director of Operations for the world’s largest recreational ski racing program, NASTAR. He has appeared in five Warren Miller movies and was a stunt skier in the feature film, “Aspen Extreme”. Bill raced for the University of Colorado and the US Junior Worlds Team. This event happened in 2004, and we first published this story back then.)

Beyond our regular guest bloggers who have their own profiles, some of our one-timers end up being categorized under this generic profile. Once they do a few posts, we build a category. In any case, we sure appreciate ALL the WildSnow guest bloggers!