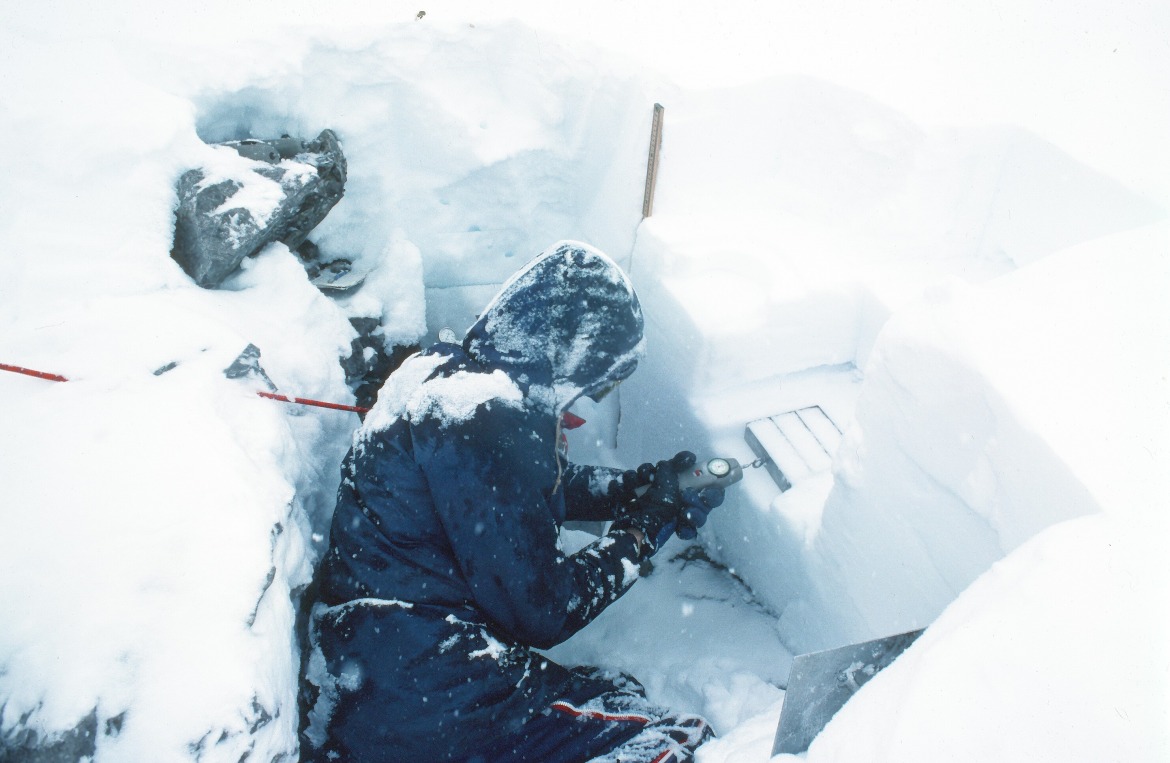

Ron Perla at a creep gage ready to be covered with snow

on a test slope next to the Alta Avalanche Study Center. The gage was built by

U of Utah, Geophysics (Prof. Bob Smith and team.)

Standing on the shoulders of snow scientist Ron Perla, the backcountry community can navigate avalanche terrain to forge a safer path and come home at the end of the day.

An early season question from a reader about the 30-degree threshold and avalanches led me to learn more about Ron Perla. As you can read here, Perla and his research have much to do with our understanding of slope angle and which slopes are likely to slide.

Our understanding of avalanches and the matrix within which we make individual, and group decisions in avalanche terrain have expanded. But the path towards a career in snow science and forecasting was much blurrier several decades ago than today.

Like all things data, there is usually a human behind all the notation, spreadsheets, and findings. In a follow-up interview with Perla, I worked with Lynne Wolfe, Editor of The Avalanche Review, to learn more about Perla and his career. You can learn more about the American Avalanche Association here.

Ron Perla: Jason, what a great chance to get some things on the record. I have much to say. I’ll throw in some history peripheral to your main theme.

My avalanche training was in Utah. In 1961, I joined the part-time, professional Alta ski patrol. In 1963 on a ski patrol sweep, I out-swam a size 3 avalanche down a gulley that had been artillery blasted. It was my introduction to the post-control release. October 1966, I moved from Salt Lake City to Alta to work for the USFS, half-time as a snow ranger, supervised by Ray Lindquist, and half-time as a research assistant to Ed LaChapelle at the USFS Alta Avalanche Study Center. In those years, the USFS closed and opened ski runs, roads, village travel, and even ski touring.

The training was fast, way too fast. My first task was to take revenge on the gulley, which nailed me in 1963, by boot packing its depth hoar. I had a lucky escape on opening day of the 1966/67 season when I test skied but should have blasted. Spring 1967, I barely survived another size 3 over cliffs when a cornice blasting operation went all wrong. I know what it’s like to be tossed around, battered by big snow blocks, and buried unconscious under the snow. Later, I participated in the attempted rescue of two young boys who did not survive. I witnessed from artillery positions size 4’s, which never failed to excite.

Ron Perla working on slab above Alta village, 1968.

Visiting scientist Charles Bradley, Montana State University, skinned

up with me and took this photo.

Turning to research under LaChapelle: we tested a variety of rescue methods and devices, including transceiver prototypes, studied snow and its metamorphism with traditional and innovative tools, and skied to numerous start zones accessible via lifts and skins to measure slab properties. We also developed a theory of slab stress and failure, studied over 100 storm reports for contributory factors, rebuilt and better equipped our study plot, measured creep angles of snow, and wrote many internal and journal publications.

The Alta Avalanche Study Center was world-class. It shared information with snow and avalanche scientists within and outside North America. It hosted visiting scientists and practitioners. It collected accident reports which were turned over to Dale Gallagher and Knox Williams for the Snowy Torrents. It held an annual school for foresters, ski patrol, military, and other select applicants. My career, my very being as an avalanche scientist, peaked during those years when I lived and worked surrounded by avalanche paths of Little Cottonwood Canyon.

In 1972, the USFS closed the Alta Avalanche Study Center. I was transferred to Fort Collins to work for Pete Martinelli. We made use of my intense Alta years to design a USFS national avalanche school and write an accompanying Avalanche Handbook. To seek information for the handbook, Pete had me travel west-wide USA, to Rogers Pass, and to a meeting in Switzerland. Also, I found time to perform more slab studies at Alta and in Colorado. I eked out a couple of publications on snow slab failure. Working for Pete with colleagues Knox Williams, Art Judson, Dick Sommerfeld, and R.A. Schmidt were productive years.

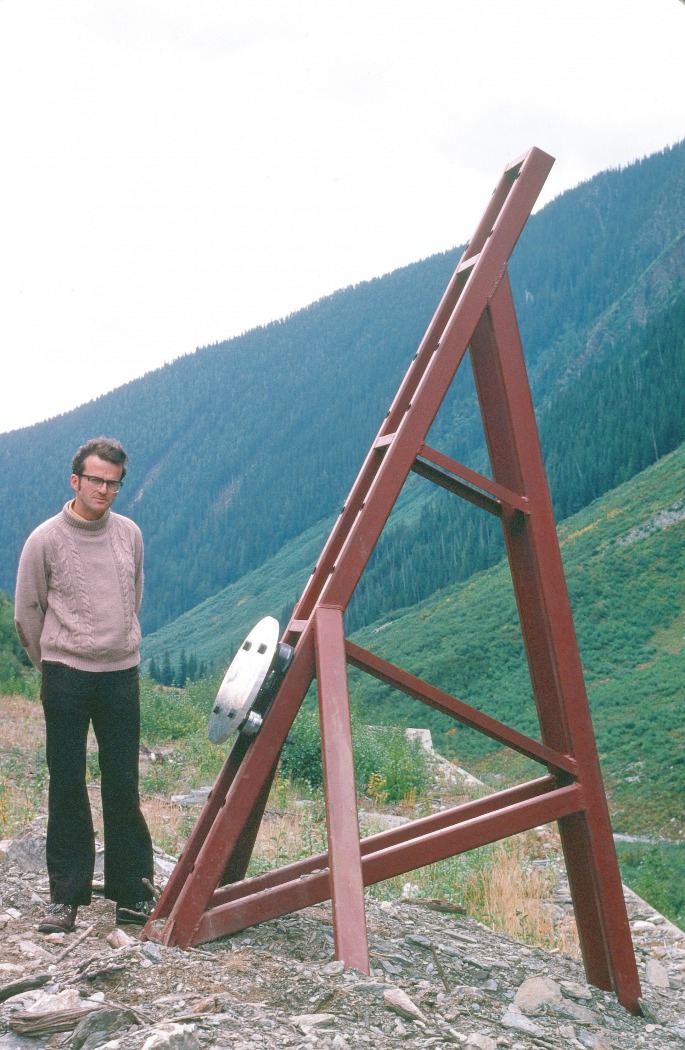

Our snow lab at Sunshine Ski Area.

We moved snow samples from the corralled Warden’s snowplot

into a cold room on the left side of the lab. Glaciology technician

Terry Beck did the lion’s share of general contracting to build the

lab as well the weather station at the top the Great Divide ski lift

(Ron Perla photo, June 1978.)

In 1974, I moved to Alberta to work for the Canadian Glaciology Division, eventually settling in Canmore. My first task was establishing a snow lab next to the warden’s study plot in the Sunshine ski area. We also built a weather station at the top of the Great Divide lift. Our main collaborator was warden Keith Everts.

Next, we established a snow lab at the top of the Whistler ski area. Chris Stethem ran it and performed studies on slab weak layers. Also, we had a fully equipped snow lab in Canmore for intricate experiments on snow samples transported down from Sunshine. Our first collaborator was computer programmer Tony Salway who worked on an avalanche forecasting model. We brought Dave McClung over from Norway to jump-start his long career in Canada. Dave continued his lab and theory work on shear strain-softening. We worked together on avalanche dynamic models.

In 1978, the Glaciology Division was absorbed by the National Hydrology Research Institute. Management deleted avalanche research. That marked the end of my hope to join other major players such as Peter Schaerer (NRC, Vancouver) and Geof Freer (BC highways, Victoria) in an avalanche centre to be located in Golden or Revelstoke. It happened anyway, 30 years later.

So I became a snow scientist under orders not to work on avalanches.

With visiting scientists LaChapelle and Jeff Dozier and his students, I continued work on dry and wet snow and its metamorphism until my 1991 retirement from the Canadian Government. However, I did manage to sneak in a few avalanche studies and publications. Today, I sit in front of my computer, modeling those avalanche vortices which tossed me around like a feather.

Terry Beck measures the strength of depth hoar on Delirium Dive, Sunshine ski area. (Ron Perla photo, 1975.)

WildSnow: Even trying to narrow down this further, what do you feel are your greatest contributions to snow science and avalanche education?

Perla: I’m not sure what will meet the test of time. Maybe some of my slab mechanics work in the USA and Canada could. My slab terminology is still used. The wedge density cutter caught on thanks to Kelly Elder’s improvement. Perhaps an early avalanche two-parameter model could, due to its simplicity. I developed a particle model of avalanche flow in collaboration with Karstein Lied’s team at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute. It was among the first to simulate entrainment and deposition patterns and to use Monte Carlo methods.

Some of my snow properties work, such as shear strength measurements, are occasionally cited. My photomicrographs of metamorphosed snow grains appear in publications.

In the dustbin of government publications, one of my favorites was measuring the impact forces of large snow blocks falling from a high tower at our Sunshine lab. The large pressure plate at the tower’s base was moved to a stand just above a Rogers Pass shed. Unfortunately, the axe came down on our avalanche work before we could get meaningful results.

On education, let’s include some publications, schools, and workshops. The USFS 1968 Modern Avalanche Rescue is hardly modern today, but it did introduce John Lawton’s avalanche transceiver, contrasted with less practical options. The USFS Avalanche handbook has survived as a template for the improved version prepared by Dave McClung and Peter Schaerer. Those handbooks are our most cited and popular publications.

Besides the USFS avalanche schools, I’m proud Rod Newcomb picked me to participate in his American Avalanche Institute schools. I’m honored Liam Fitzgerald asked me to give a banquet speech at the Snowbird ISSW. That gave me a chance to revisit the life and death struggle of a USFS snow ranger.

I devoted two years to organizing a 1976 international workshop in Banff and editing its proceedings; I was the primary motivator and helped organize workshops to honor Monty Atwater, Ed LaChapelle, and Binx Sandahl.

I’m grateful to Bruce Jamieson (retired professor, University of Calgary) for many years of scientific exchanges. He invited me to give a series of talks on avalanche dynamics to his graduate class at the University of Calgary. He summarized much of my output on his www.snowavalanchearchive.com.

WildSnow: Where did you first get the inclination you would dedicate your life to snow science?

Perla: In 1966, as an apprentice to Ray Lindquist and Ed LaChapelle. Both were my heroes before then, but the move to Alta was decisive. Be prepared for funding problems if avalanche research is your career.

WildSnow: Can you give us a brief academic background so that others can learn about your course of study?

Perla: My academic background was desultory. It started with an undergraduate de- gree in electrical engineering (I worked as an electrical engineer for seven years.) I added on education classes to qualify for teaching in Salt Lake City (I taught high-school physics for two years.) My Ph.D. (U of Utah) is in meteorology, although more than 50% of my classes were applied mechanics, physics, and mathematics.

I’m compelled to add that snow and avalanche studies benefit from a variety of backgrounds and skills. For example, much of the Handbook’s popularity is owed to Alexis Kelner (Salt Lake) with his combined talents as an illustrator, photographer, mountaineer, and ski-tourer. Let’s remember that Monty Atwater’s Harvard degree was in English Literature.

Medics tell us what happens when we are bashed or buried by an avalanche. Lawyers achieve a high degree of snow and avalanche wisdom. They ask the hardest questions. Good luck holding on as an expert witness.

Mostly, I share with other avalanche workers many years in the mountains.

Upslope of a highway shed at Rogers Pass. Terry Beck next to our impact plate mounted on a steel stand installed earlier by Peter Schaerer and Paul Anhorn for their pressure measurements using small pressure cells (Ron Perla photo, 1978.)

WildSnow: What attitudes and behaviors have you seen change over the years?

Perla: I can’t give you facts and figures; others can. Here’s what I’ve heard and read. Despite the enormous increase in backcountry use, despite increasing behavior to ski and ride lines we could never imagine in the 1960s, avalanche fatalities are not increasing to match those trends.

Why?

Surely, associations, centers, websites, and educators, in general, are responding to match those trends. Surely it’s also because today’s risk-takers are increasingly more skillful backcountry skiers, riders, and escape artists. Equipment is improving. Guides are more professional (early heli-skiing had a sad number of fatalities.)

But there’s something else: call it collective consciousness in the backcountry. An increasing number of backcountry users correlates with increasing observations and tests. Thus, safety can be enhanced by numbers if there is increased communication — verbally, visually, and electronically. This appears to be the case.

WildSnow: What has stayed the same?

Perla: Nature’s eternal randomness. Her power to surprise.

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.