We learn early and often in avalanche education that slides are more likely to occur on slope angles of greater than 30 degrees. We know this as the 30-degree threshold. Here’s some backstory on the good work of Ron Perla and the threshold that keeps us tuned in towards solid avalanche awareness.

The question came from a reader: It had to do with the 30-degree slope angle threshold we’ve come to know from snow science and applying avalanche risk mitigation in the field. Specifically, the reader wanted to know what that numerical threshold is based on.

As backcountry skiers/riders know, the threshold means keeping an eye out for slopes that are likely to slide; often, there are exceptions, but we look for that 30-degree slope and below if avalanche conditions are ripe. Decades of data suggest that 30-degree and lower slopes are less likely to avalanche in dry snow conditions.

Wisely, I defer to those who know best. I turned to the Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center’s Doug Chabot, who set me on the right track.

Chabot wrote that the 30-degree threshold stemmed from research conducted and published in the 1970s by Ron Perla.

“[Perla] measured slope angles on 170+ slopes, graphed it out, and saw that slopes 25-30 rarely had slides on them, but at 30 degrees, it ramped up,” noted Chabot. “Thirty degrees is the general lowest angle of repose for snow. Wet avalanches are different, but for dry snow, almost all slides occur at 30 degrees or steeper. Since Perla’s research, we have measured thousands of avalanches around the world, and there is a consensus in the community that below 30 degrees is not avalanche terrain.”

Love those Internet wormholes. Let’s dip our toe into Perla’s findings.

Chabot clued me into the 1976 U.S. Forest Service Avalanche Handbook. There, on page 67, the Handbook states:

“The exact critical angle of repose depends on the temperature, wetness, and shape of the snow grains. For example, wet, slushy snow has very little strength for its weight and can avalanche off slopes as gradual as 15°. Newly fallen snow has relatively low cohesion but generally has enough strength to cling to 40° to 50° slopes. How- ever, if the new snowfall is cold enough, avalanches of cold, dry snow may occur on slopes of 30° to 40°because sintering cannot proceed fast enough at the cold temperatures to anchor the snow. Rounded graupel crystals generally will not cling to slopes steeper than 40° and often roll down steep slopes like ball bearings. In the Andes, conditions exist that permit thick slabs to cling to inclinations as steep as 50° or 60°. ”

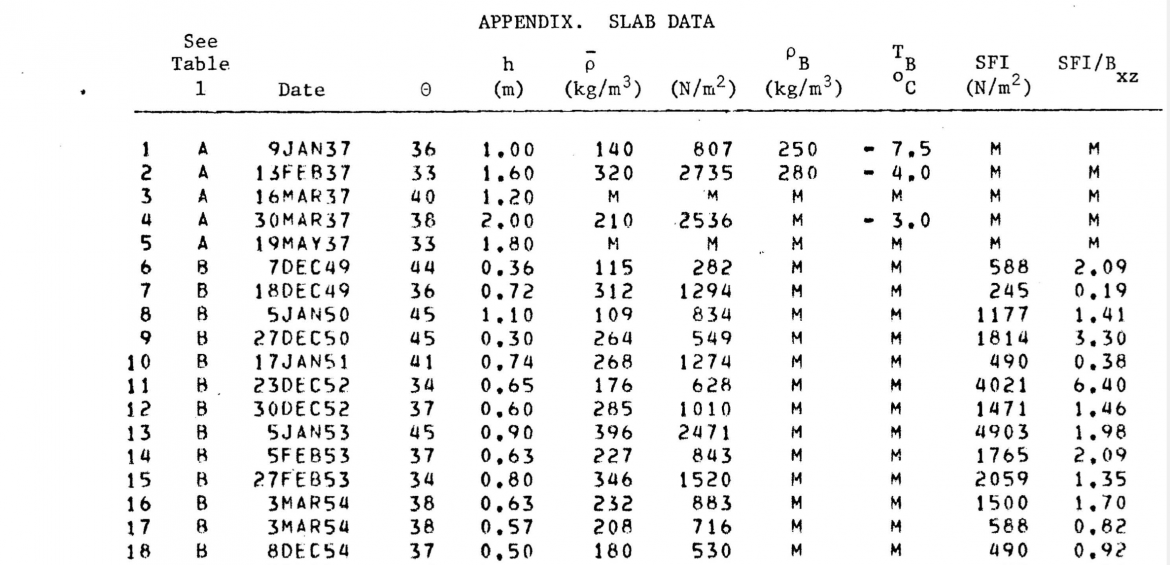

A screenshot from Perla’s “Slab avalanche measurements.” The slope angle is noted in the fourth column from the left.

Snow science has advanced since then, but the basics, with some of the slope angle threshold exceptions, are laid out for us.

Perla’s Slab avalanche measurements, Perla includes slope angle information on more than 200 slab avalanches. We see the dataset from which the 30-degree threshold concept began.

Thanks to Chabot (and the reader) for the question and answer and a chance to revel in Perla’s good work.

Find more of WildSnow’s Avalanche resources here.

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.