He’s got the boots, but where are the planks? And for that matter, where is the snow? Jon Waterman on Humboldt Peak, 1988, Crestone Needle and Peak in background.

March 1989 — Sangre de Cristo mountains, Colorado. After a brief headlamp stroll to timberline, I stopped for a food and water break at quarter-mile-long South Colony lake. A bullying wind propelled jaunty, white-crested waves across the water, sieved through my fleece jacket and chilled my damp skin. Lit pink by the dawn, a train of cuticle shaped cirrus clouds raced overhead, like a fast-motion movie. A dull roar projected from the ridges above, punctuated by odd ripping noises I imagined were invisible whirlwinds.

I shrugged into my shell parka, zipped it to my chin and pulled my ski goggles over my eyes. The mellow, spruce-scented breeze I’d enjoyed at the trailhead was a friend no more.

Ignoring the portents of the sky, I continued scrambling up the wind-dried gravel and rock of Broken Hand Pass. If Crestone Needle held any skiable snow, the wind was stripping it faster than a painter wielding a disk grinder. Even so, I wanted to see the only known ski route on the peak, to plan for when I might find it in condition.

To lighten my load, I dropped my skis on the ground. A spicy gust moved them a few inches towards Kansas. I anchored the now useless planks with a few football-sized rocks, then blundered ahead, bent at the waist like a doddering old man. Seeking stability in the gale, I clawed my gloved right hand against rock outcrops and boulders. I held a ski pole in my left hand. After a few skittering attempts to use it as a cane, my grip slipped, leaving the shaft hanging from my wrist by its nylon strap. A gust flagged the pole horizontally from my side, then flipped it towards my face like a riding crop.

A sinister roar crescendoed from the rocks above. I paused, braced. My ears popped, then a 100-mph blast knocked me to my chest and peppered my face with sand and small stones. I did a 180 on hands and knees, butt-slid down the gravel to my skis, returned to Westcliffe, and spent an hour under the motel shower. I could hardly believe it. The wind had nearly blown me off a mountain. In little old Colorado.

I was forty-two peaks into my project to ski all fifty-four Colorado “fourteeners.” My first of the far southern mountains, here in the Sangre de Cristo just the day before, had been a shiny, optimistic morning of cardio power and perfect turns. I’d been sandbagged.

* * * *

Ask any skier of Colorado fourteeners: “What’s the crux of doing the entire list of 54?” Unless our protagonist is enjoying near miraculous luck, they’ll tell you the trick is scoring the nine fourteeners of the Sangre de Cristo mountains. It was like that in the 80s and early 90s, when I and a handful of other skiers were figuring them out. And despite the advantages of today’s modern communications and gear, much of the challenge remains.

By my definition, the Sangre cordillera snakes 120 miles south from Salida, Colorado to the New Mexico border, through Colorado’s least populous high desert region. Viewed overhead with the help of Google, the range appears as a skinny chain of peaks, buttressed by rolling foothills soon tapering to vast valleys. This extraordinary topography appears deliberate, as if Atlas himself had scooped the earth from either side into his jumbo version of dry-land sand castles. And dry the Sangres are — often remaining unskiable for months — sometimes for an entire season.

Two of the Sangre fourteeners (Lindsey and Culebra) stand well away from the others, while the remaining seven ‘teeners comprise two groupings. The cliffy aretes of the Crestones rise to Kit Carson Peak, Humboldt Peak, Crestone Peak and Crestone Needle. The Sierra Blanca group — of slightly more behaved topography — encompasses Blanca, Ellingwood and Little Bear peaks. Any of the Sangre peaks are worth flirting with, yet the Crestones are where you’ll find the steepest and most intricate lines. Indeed, with one exception they present themselves with such vast reaches of cliff and rock it requires the faith of a child to contemplate navigating them on skis, instead of crampons or boot soles.

When I began dreaming of Sangre ski descents, around 1987, I knew through the grapevine of only two fourteener summit skis throughout the range. Those being the Fitz/Pfeiffer crew’s firsts of Humboldt and Kit Carson, in the Crestones just a few years prior (see footnote). Skiers had never touched the seven remaining Sangre fourteener summits. These days, hard to imagine.

Beyond the aridity of the Sangres, determining weather and snow-cover was as much a mystery as the lost Spanish treasure said to hide in the valleys below. Even for those dwelling nearby, the best weather predictions were something akin to licking a thumb and holding it in the wind (or waiting five minutes, as Coloradans were fond of joking). Because I lived about 150 miles to the north, neither option stood a chance. Instead, all I had was irrelevant television weather and guesswork. Were there routes on the yet unskied peaks? And incidentally, did they ever contain snow?

The only answer was to head down there and find out. From the late 1980s on into the 1990s, I suffered the white-knuckle deer-dodging six-hour drive over two dozen times, spent a night or two — and most often returned home with nothing but gasoline receipts. It took me more than forty days to ski just the nine Sangre fourteeners. Surely, in some statistical way, the odds of summitting Mount Everest are better.

* * * *

Going on May 1988, I invited a group of mountaineering industry friends to accompany me on my first Sangre de Cristo foray. The plan: We’d ski the easiest of the four Crestone fourteeners, Humboldt. The guidebook I was using (I’d yet to write mine) stated that Humboldt “sprawled like a giant anthill.” Clearly this was the perfect introduction for a Sangres summit ski. Or at least a way of forestalling the mysterious monuments to uncertainty looming across the valley south of Humboldt — that be cliff-skirted and unskied Crestone Needle and Crestone Peak.

Our all-star cast comprised Black Diamond CEO Peter Metcalf, BD’s Scarpa distribution manager Kim Miller and his wife Rowan — they’d all driven from Utah — and alpinist-writer Jon Waterman. According to Kim, Metcalf wanted to see how my 1970s career as a rock and ice climber had shifted to that of a ski alpinist. “Besides, BD is getting more and more into skiing,” he explained. “I want Peter to see what’s going on in another part of the country.”

Skiing Wasatch powder or enjoying the European classics seemed wiser alternatives for a well-heeled CEO than the unknowns of the piddly Sangres. But hey, if the big boy wanted to slum with us Coloradans, who was I to complain? Besides, I had a nascent writing career and needed all the help I could get. Perhaps I could take the idea of sponsorship beyond that of a free hat?

I spent the entire six hours of my solo drive fantasizing about proving the worth of Colorado adventure skiing — and establishing myself as the sponsored opinion leader of same.

When I pulled into the trailhead parking, the others were already there, dressed in athletic shorts and T-shirts, their skis and boots strapped to their packs. No messing around for the corporate guys. A lump formed in my chest. I’d better deliver.

Then I looked up, and my delusions of grandeur evaporated like a snowflake on hot granite.

Every peak in sight was the grey of a two-day-old corpse. If any snow hid beyond our view, it would yield nothing more than patch skiing. A wave of profound embarrassment washed over me. I hid my feelings, smiled, laughed, and said something about enjoying the hike.

After overnighting at South Colony lake, Jon and I left our skis at camp and hiked the summer dirt-trail to the top of Humboldt Peak. The next day all of us skied a 400-foot patch of snow above South Colony lake, hiked out, then parted ways.

* * * *

A winter of Aspen area powder skiing rehabilitated my Sangre shattered spirit. I returned the next spring, solo, guessing there might be snow. You know, a broken clock is right two times a day and all that. In the light of a just risen sun, I parked my snowmobile at the base of a 3,000-vertical-foot snow pitch dropping from the Humboldt summit like an escalator to paradise. After two hours of hypnotic step-kicking, I was sitting on top, chatting on my ham radio with an auto-parts store owner in Westcliff. Safety check completed, I clicked into my skis and flowed down the wind-smoothed slopes, cloudless bluebird above, while the vastness of the Wet Valley sprawled east below me into the morning haze.

Finished with Humboldt, I sat on my sun-warmed black vinyl snowmobile seat, uncapped my thermos, and feasted on the stunning line I’d just skied. For a moment or two I forgot that no other Sangre were giant anthills, and that finding skiable snow on these peaks was as rare as seeing a kangaroo in the herds of cattle on the ranchlands below. I rolled back into Westcliff at ten in the morning and stopped at the auto parts store. The owner had just unlocked the door. As he rang up a quart of oil I needed for my truck, he said, “Were you really on top of that thing when you called? And now you’re here? What did you do, fly?”

After a day like that, why stop? So the next morning I went for Crestone Needle. Where I joined up with the wind god Aeolus for my “reconnaissance” mission.

* * * *

I suppose my being an optimist is a positive character trait for an alpinist. Because going on faith sometimes works. So it was that after my wind-inspired motel rest day, I found myself kicking steps up a forty-five degree couloir paved with frozen gravel, skis strapped to my pack, nearing the top of Crestone Peak, the twin fourteener a mile west of Crestone Needle.

When I reached Red Saddle, an oxide burnished col just below and east of the Crestone Peak summit, not a crumb of snow was in sight. Flashing back to the previous year’s snow-starved debacle, I dropped my skis — why carry the weight? — and jogged up the last few hundred feet of gravel and dirt to the summit. There, extending perhaps fifty feet from the top to the edge of the south face, a patch of snow greeted me. Ever curious, I steeped a few yards from the summit cairn and peered down the face. Could there be something?

I’ve had hundreds of exciting moments on mountain tops. This was top ten. I could see the snow I stood on was connected to a sheet of white, which then connected left to a partially-hidden couloir system dropping to the base of the peak. It was steep. Maybe a little complex. But it looked to go — likely a first descent. I turned and scree-ran down to Red Saddle, grabbed my skis, and jogged back to the summit. The skiing took maybe a half hour, but the mystery so engaged me it felt like ten seconds. Scrape cautious turns above a cliff, then a hundred yard traverse, carve rhythmic arcs down a deeply riven couloir, sidestep out of a blind alley, traverse again, pump wide-open arcs on corn snow soft as cat fur to a small lake in the basin below. Crestone Peak was off my list. Number 43 out of the 54.

I caught a few more Sangre fourteeners that spring of 1989, then managed another three the following spring of 1990, just before my wife birthed our son in June. Now with a neonate at the homestead, I wasn’t keen on alpine heroics. So I skipped the Crestones that next spring.

* * * *

In spring 1988, my Telluride extreme skier friend Sandy East, along with Peter Inglis and Tyler Van Arsdale, accomplished the first — and then still only — ski descent of Crestone Needle. “It’s got a steep section,” was all Sandy told me about it. That was enough. Once my demolished ego recovered (I’d counted on nailing the first), I was just glad to know this sharp and pointy chunk of rock had a ski route, and sometimes enough snow to make it happen.

* * * *

Two years had passed since Sandy opened up the Needle route. Two years of too dry, too far and still too mysterious. But it was time. I guessed at a snowy week in April 1991, and called photographer Glenn Randall.

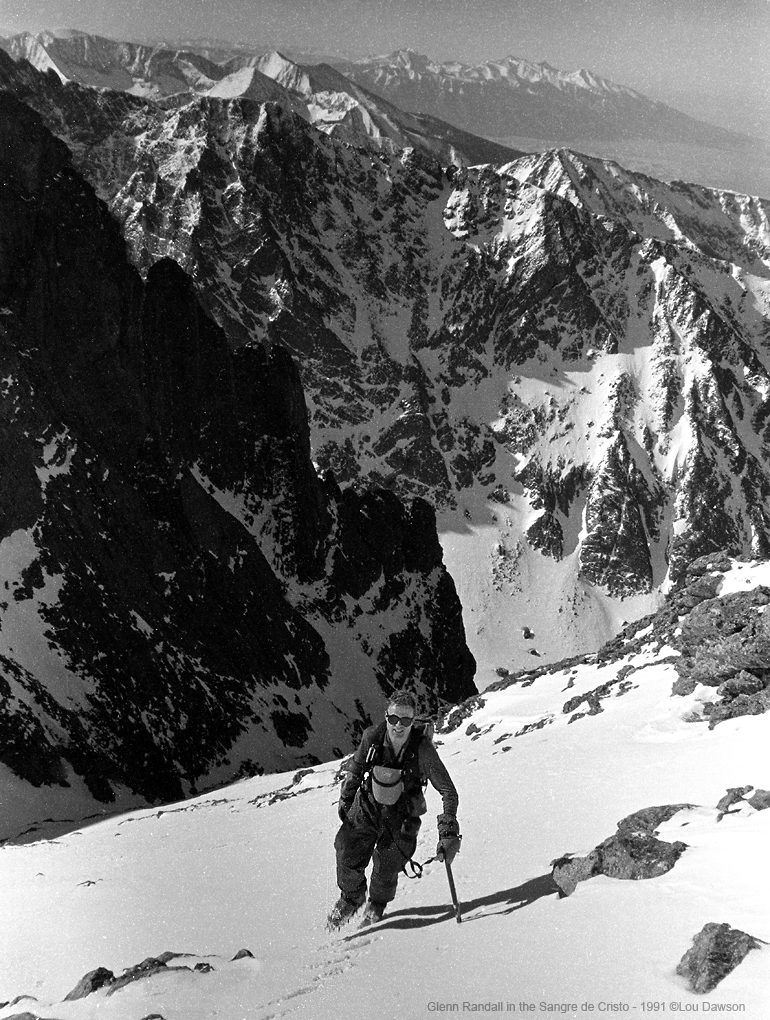

Glenn was a golden-haired, stocky climber with mountaineering chops he’d gained on world-class mixed routes such as the south face of Alaska’s Mt. Hunter. We’d met around 1982, when he was writing his book, Vertigo Games, covering the 1970s era of Colorado climbing (which included exploits by Michael Kennedy, myself and others of our Aspen climbing cadre). Glenn had subsequently devoted himself to photography. Unlike the blank stares I often received regarding my ski-the-teeners project, he understood what I was trying to accomplish as a valid endeavor of alpinism, and wanted to photograph the culmination of the project. He was not a skier of the steeps, and planned on leaving his skis below the crux sections and concentrating on burning film. I appreciated this immensely, as I’d found that extreme skiing was often best practiced without the distraction of a partner on planks, taking the same risks.

Only one question remained: Had I guessed right about the snowpack?

For a change, I had. As we turned the corner at Broken Hand Pass and got our first view of the route, I nearly fainted. More snow than I’d ever seen at 13,000 feet in the Sangres filled the thready couloirs to brimming.

This thing is skiable! Yet for how long? Hours? Minutes?

As we rounded the corner at Broken Hand Pass, I nearly fainted, astonished to see more Sangre snow then we could ever had imagined. Glenn Randall photo.

The line faced southerly or directly south. As we traversed to the climbing route from Broken Hand Pass, small tongue-shaped snow sluffs fell from the margins of sun-warmed rocks. Now and then a snow pinwheel rolled down, bounced once or twice, then burst into a scattering of slushy pellets. When I paused and listened, the sound of water trickling off the rocks above reminded me of a garden fountain.

I stopped, planted my ice ax, and turned to Glenn. “I don’t know about this,” I said. “The day is already cooking, it’s not very nice up there.”

“The sun’s just been on it a few hours,” Glenn said. “I don’t think it’s loosened up underneath yet, let’s try it.”

“You’re right, if it’s going to avalanche, that’ll happen after noon, we’ve still got hours. But man this snow is pure junk. Let’s climb a little ways, see how deep we sink. But let’s take a layer off first.”

We stripped to our T-shirts, slathered sunscreen like putty and donned our bill-caps — mine had a red checkered bandanna my wife had sewn into the rear to protect my neck, something like those Foreign Legion hats in the movies. Glenn began stomping steps into the muck. I followed two steps behind, out of range of his razor-sharp crampons. We were soon sinking above our knees. Rather than planting my axe, I found myself punching my entire left arm into the snowpack then yarding on it for upward progress. This continued for about 500 vertical feet, when our boots found a shin-deep solid layer under the top-coating of powder.

Our speed doubled. Instead of wallowing, we were climbing.

From my position behind Glenn, I watched the skills his Alaskan snow and ice ascents had imprinted on his soul. He held his ax like the tool grew from his hand. The spikes of his crampons passed his baggy shell-panted calves with perfect clearance, never hooking fabric, while taking the most efficient trajectory possible. He was fit, too, breathing steady, smiling when he stopped and turned to discuss the route. To have a partner this competent. A rare thing.

After winding up and around a few blocky rock outcrops, we wallowed over a snow-covered fin and entered the couloir. Ten more minutes of stomping brought us to a headwall where water trickled over a bluish white fifteen-foot frozen waterfall. We could climb the waterfall. But it wasn’t skiable — not steep enough to hop over, too steep to sideslip.

We downclimbed a few yards, exited the couloir, and worked out a climbing route up skiable terrain that eventually reacquired the couloir. After that, the climbing crux involved nothing more than rubbing the occasional handful of snow on the back of our necks, to prevent death by heatstroke.

Glenn left the summit first and downclimbed fifty feet face-in, kicking his boot toes through the soft top layer snow into the ice beneath. He pulled his camera out, yelled, “Ready.”

This was the type of summit I liked, nothing higher than me within sight, ski tips hanging in the air, gravity like a rope tied around my waist with a block of concrete dangling on the end. I launched. Glenn burned film. The resulting wide-angle image became a magazine cover, me in the middle of a hop turn, blue sky above, a vast slice of dark alpine rock and shining snow arrayed below my skis.

The first turns were smooth, easy. Each pushed a load of powder down the couloir, leaving it clean of avalanche danger. I relaxed my fear brain and stopped to catch my breath while Glenn re-positioned. The ground here was steep, around fifty-five degrees.

“Ready.” As I always did on the steeps, before launching I shuffled my skis to check for glide. Nothing happened. When I yanked a single ski upward from the slope, the ten-inch thick mass of ice and snow adhering to the base felt like I’d strapped on an eight-pound ankle weight for a gym session.

I was stuck like a mouse on a glue trap.

The tantrum came easily, releasing my pent frustration in a screaming fit. Glenn observed in silence, no doubt wondering at my mental competence. I detest partners having temper tantrums during athletic ventures, sometimes blacklisting them from my trips — here I was indulging in my own embarrassing histrionics.

Glenn kept a safe distance, his facial expression showing controlled calm. I wondered if that was just a facade — perhaps he’d blow up at me any moment, tired of my hissy fit. “Can I help somehow?” he said.

“We’re nearly aborted,” I blurted between breaths. “Unless I scrape the ice…off my skis…so I can turn…instead of climbing down on foot. It’s too steep and loose here for me to take my skis off, then put them back on.”

While standing on the steep slope, in the middle of the couloir, I lifted one ski and attempted to scrape it over the other, thus performing an awkward pigeon-toed dance. No joy. The goop adhered like epoxy.

“I don’t see any alternative except you pulling your shovel out of your pack and scraping my skis while I stand here with them on my feet,” I said, desperate to avoid yet another Sangre failure. “I’ll hold them up one at a time. You think that’ll work?”

Glenn shrugged off his pack, pulled out his aluminum avalanche rescue shovel, and positioned himself just forward of my ski tips. “I’ll try,” he said.

I raised one foot at a time, up and forward, picking up the ski so the base faced Glenn. He then hacked away the sticky ice and snow like he was digging into his backyard garden.

As I stood shuffling my skis, to prevent the ice from reforming, Glenn moved to the side of the couloir and dug out his camera. “Ready,” he called.

I felt the pull in my abdominal muscles as I lurched upward, yanked my skis out of the glop, and managed three turns. Glenn made three photos. My skis wadded up again. Glenn stowed his camera, downclimbed with ice ax in one hand and shovel in the other, and repeated the process. Then again.

The tedium was unbearable. I thought of unclipping my skis and tossing them off the mountain, then downclimbing the fine set of steps Glenn had kicked into the couloir below.

Then, like someone flipped a switch marked “perfect snow,” my skis were free. I was playing again, hopping through easy jump turns, certain that after this and so many other trials, finishing my last two peaks of the fifty-four just might be possible.

Couloir Magazine cover, 1993, Lou in Crestone Needle south couloir. Click image to enlarge. Check out Glenn’s website.

Various publications featured Glenn’s photos — fourteener descent! I chuckle when I run across the tear sheets in my scrapbooks. Rather than recalling any heroics on my part, I only remember Glenn kindly employing his shovel as an ice-scraper, thus preventing my tossing a new pair of Kaestle Tour Randonee skis down the cliffs of Crestone Needle.

Photographer Glenn Randall in the Sangres, 1991. I was awed by how much weight he hauled around in photo gear.

FOOTNOTE — The Fitz Crew

From 1978 to 1987, brothers Howie and Mike Fitz, along with their friend Bob Pfeiffer and others, executed their own “ski the fourteeners” project somewhat concurrently with mine. Without the facilitation of modern communication, I’d known only vague rumors of them until we met at a slideshow talk I was giving in Denver, around 1987.

Bob Pfeiffer (L), Mike and Howie Fitz, at South Colony Lake 1988, Humboldt Peak in background, “the giant anthill.”

The vibe of that first meeting was congenial, with an undercurrent of pride not in ourselves, but instead regarding our ideas. It was as if we’d stumbled onto some sort of forbidden knowledge. “We need not travel all the way to Europe to enjoy… skiing along the “high routes,” Mike and Howie wrote in a 1980s Rock & Ice Magazine article about their fourteener adventures.

While there might have also have been a touch of competitive spirit between us, at the time none of us knew whether all the fourteeners were skiable in the modern sense (from on or near the summit). That, and the safety-aware style we all engaged in, put a damper on any sort of race to the top.

In the end, one of the Fitz crew had medical problems that quenched his ski mountaineering career. Around 1989 Mike told me that since his primary crew of three had agreed to finish the project together — and they’d left a few of the most difficult till last — they were quitting after about 47 peaks. As a goal oriented guy who was doing the project solo, I experienced a momentary bewilderment at this, soon shifting to respect for such a deep friendship. I wondered if I had that kind of character.

In a beautiful gesture of generosity and mountaineering spirit, Mike loaned me his crew’s journals as well as their complete photography library, which I duplicated and added to my archive. Their aerial images trimmed months — if not years — off the duration of my skiing all 54 peaks. I can never thank them enough.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.