Excerpt from Wild Snow, A Historical Guide to North American Ski Mountaineering and Classic Ski Descents

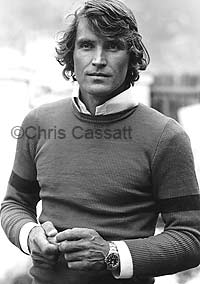

Fritz Stammberger circa 1971, photo by Chris Cassatt used by permission, as part of book promotion. Reproduction or digital publishing by permission only.

As a young man in 1970, I was with a group winter camping on Ski Hayden Peak near Aspen. We’d pitched our tent in view of a steep (45 degree), avalanche-prone headwall. We’d never considered skiing this face, it was just a place where we watched avalanches. Suddenly someone voiced a startled cry and pointed to the wall. It wasn’t a slide this time, but a skier coming down! He’d make a powerful traverse, knock off a good-sized avalanche, then turn around and make a few turns where the slide had scoured. Then he’d do it again.

We watched this display of courage and athleticism in uncomprehending amazement, the way Native Americans must have watched the arrival of Columbus. It was skiing completely out of our experience — transcending reality. That encounter stands as my enlightenment as a ski mountaineer — that day I became as much a glisse alpinist as a climber. The skier we watched was Fritz Stammberger.

Stammberger was an imposing man with a weight lifter’s physique, thick German accent, and the poise of a rugged individualist. He’d immigrated to the U.S. from Germany in the early 1960s, and settled in Aspen as a printer and ski instructor.

Fritz was a committed alpinist and a bold skier. In 1964 he became the man with the highest ski descent to that date when he skied from 24,000 feet on Cho Oyu in Tibet (after making the first oxygenless ascent of that 8,000-meter peak, the seventh highest mountain in the world). Unfortunately his accomplishment was marred by controversy: he skied down Cho Oyu to get help for two companions who died on the mountain, and pundits later claimed the deaths were caused by Stammberger’s neglect. History appears to exonerate Stammberger, but his mountaineering career was dogged by that initial debacle.

During his years in Aspen, Stammberger spent countless days skiing mountains such as Ski Hayden Peak and Grizzly Peak (a 13,988-foot Colorado peak with a beautiful couloir dropping from the summit). His training was legendary. On all but the coldest days he would ski without gloves, and he’d walk around town with dripping snowballs clenched in his hands. Almost any winter morning, you could see Stammberger’s tall figure striding impossibly fast up the ski area on his alpine touring skis—his favorite training.

Like a Nietzschean Ubermensch, he’d wait until winter, then make first winter ascents of mountain walls as visionary and difficult as any climbs of similar size done elsewhere in the world. In 1969 he made the first winter climb of dagger-like Pyramid Peak, one of Colorado’s last fourteeners without a winter ascent. In late winter of 1972, he skied with Gordon Whitmer to the north wall of 14,130 foot Capitol Peak, where the pair made a bold directissima.

While Stammberger’s creativity was fabulous, mixed with his aesthetic and playful spirit was a healthy dose of one-upmanship. Once, he and I were having a conversation about local climbing. I had a reputation as somewhat of an accomplished rock climber, but at that time had not done much alpinism. Fritz’s assessment: “Lou, you are too much the spider,” spoken of course with his heavy German accent. In Aspen politics he soon established himself as a radical, chaining himself to a tree to prevent a building from going up, and marching in a parade with a sign reading “Public Castration for all Bycicle Thiefs [sic].”

Fritz was was obsessed with trekking and climbing in the Himalayas. It appeared he realized the only way to raise money for such trips was to make a name for himself. So while his mountaineering continued as a personal endeavor, he also took an obvious turn towards self promotion. (I don’t write that in negative sense, it’s what you had to do in those days to get any sort of sponsorship.)

European extreme skiers who were creating their own legends, and Fritz no doubt noticed. Moreover, he was good friends with Aspen newspaperman Bil Dunaway, who had helped jump start modern European extreme skiing himself when, in 1953, he made the first descent of the North Face of Mount Blanc in France (along with French alpinist Lionell Terray). Dunaway had a good sense of mountaineering politics, and Stammberger’s association with Dunaway no doubt inspired what followed. Fritz could ski and climb as good as anyone, so he did.

Outside of Aspen is a double-topped fourteener called the Maroon Bells. Known as the “Deadly Bells” to local mountain rescue teams, the mountain has claimed scores of lives, and still makes casual climbers quake with fear. It’s steep, striated with relentless cliff bands, and built with rock so loose the climbing often resembles scrambling up a gravel pile. With the tight snowpack of spring, however, the Bells mutate. They’re safer and easier to climb for those knowing snowcraft, and they become skiable.

In 1971 few people knew the secret of Maroon Bells snow, but Stammberger did. On June 24 he cramponed up the north face of North Maroon Peak (the north Bell), donned his planks, and skied back down. Even by today’s standards the descent wasn’t easy: Stammberger fell over a 15-foot cliff, and skied a narrow section exceeding 50 degrees. Moreover, he used no ropes and had no support team. Stammberger’s feat amazed the locals and was trumpeted in the Aspen newspaper. Yet as with the coverage of Bill Briggs’s Grand Teton ski that same spring, the Maroon Bells ski descent was too far from North American ski reality to receive much mainstream press.

After his Maroon Bells descent Stammberger endured a frustrating series of failures in the Himalayas, eventually meeting his end while solo climbing in 1975 on Tirich Mir in Pakistan. A year before he disappeared, Fritz married Janice Pennington, a former Playboy Centerfold and television starlet. Pennington became obsessed with finding Fritz. Convinced by visions and psychics that he was still alive, she enlisted the help of everyone from private investigators to Elvis Presley.

Despite the best efforts of his friends and family, Fritz was never found. Bil Dunaway is convinced he died on Tirich Mir. Pennington went on to write a book about her search for Fritz, concluding that he’d been recruited by the CIA, then died in Afghanistan during the jihad fighting of the early eighties. Whatever the case, Stammberger’s spirit lives on to inspire North American glisse alpinists.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.