Avalanche accident sites. Visiting is like looking at a historic battlefield. You don’t see much evidence of the tragedy, but you know the history. Emotions well up. You get slammed with a fist of reality the size of a mountainside.

Yesterday in Sheep Creek, Loveland Pass, we got slammed. We could still see the rescue holes, so it wasn’t all imagination. With respect to the deceased’s loved ones I won’t go into detail on that. Suffice it to say that once you’ve seen the snowy crypt where a body was recovered (or hopefully a person rescued alive), your avalanche safety approach will be forever altered. This was my fourth view of the holes, including my own. I’m not sure I want more. In fact, I’m sure I don’t. Perhaps this is my last site visit.

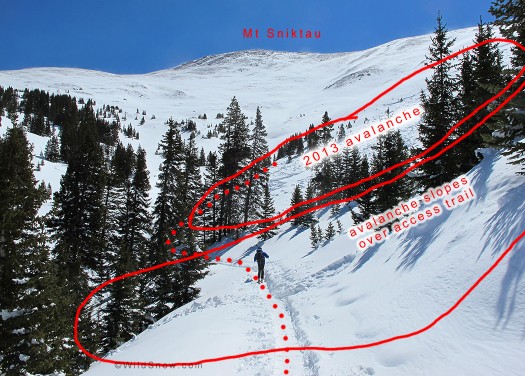

What you see from the trailhead looking southerly. I was amazed at how dangerous this place is. You step out of your car, and about twenty feet later you are crossing below an obvious avalanche path. A few hundred yards south, you step onto the slope that killed the five individuals last weekend. There is no safe way past the first paths that threaten the access trail, but if you deviate easterly when you reach the second path (that caused the accident), after a short bit of exposure you can follow a safe route up the drainage into the attractive lower angled terrain. Click all images to enlarge.

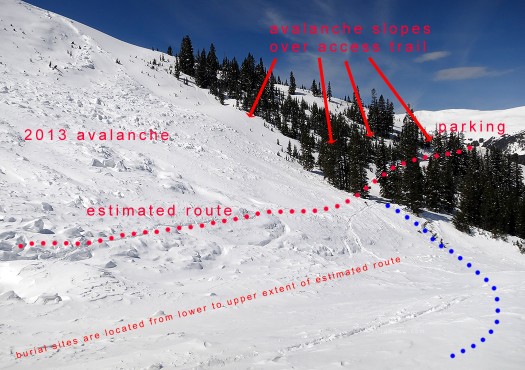

Looking westerly from the safe zone, parking to right. Loveland Pass is a short drive farther up the paved road. Red dots indicate estimated route of accident group. Of all our photos, this one shows how truly scary this zone is. Step out your car door and you're immediately in danger. Click to enlarge.

But the visit to Loveland Pass had to be done, as this accident involving six simultaneous burials and five deaths was so heinous, so horrifying as to need more fact-based interpretation. Indeed, to be fair to both the living and dead the site visit was mandatory for honest blogging, so we could look at the situation in the light of normal fun seeking backcountry recreation — not the cold prose of a CAIC report constrained by legal concerns and limits on raw interpretation — not a newspaper report constrained by ignorance or word count limits — and not our own guesswork about the terrain.

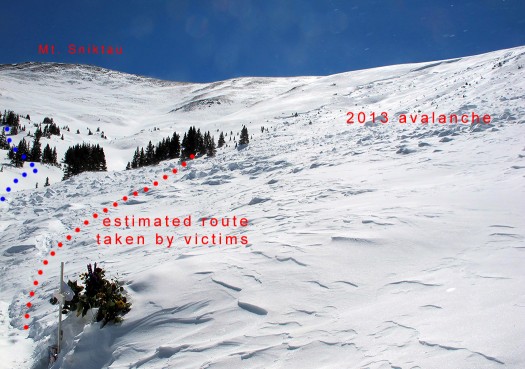

Another view of the approach trail. Red dotted line marks estimated route of accident group. A dangerous spot with obvious avalanche slope to your right and terrain trap to your left.

Yes, we all make errors. So was this accident the result of normal human error or did it somehow exceed the normal bounds of human behavior?

While we of course cannot know the final truth, I’d caution any readers to not dismiss this as normal human error. Instead, what we appear to have had is some kind of very unusual event wherein a group of six backcountry skiers and snowboarders, all of whom had been exposed to basic avalanche safety concepts and several of whom were well educated either formally or informally, ignored or forgot basic safety protocols. (Please note, I’ve edited the preceding a bit as I’d initially made it appear we knew the group had a high incidence of formal avalanche education, while it’s more likely it was a mixed group in terms of training.)

How do I assume this was not a normal error? I’m here to tell you that when you step out of your car at the Sheep Creek parking, ten feet later you are walking under a deadly avalanche path. A slope that is northeast facing, obviously wind loaded, drops into a tree studded terrain trap, and averages 31 degrees steep. According to CAIC the perfect slope for self immolation on April 20th 2013, the day five men were killed.

Only this isn’t where last week’s group died.

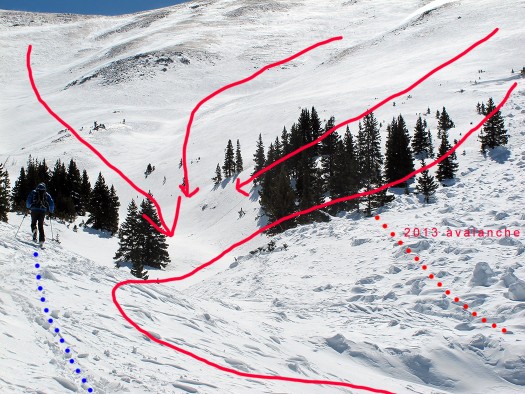

The six made it safely through the 200 yards of possibly deadly approach trail, only to make the odd decision to continue breaking trail on the toe of a large and again deadly avalanche path. This when by simply deviating twenty or thirty feet northeast from their course and making a very short crossing of the lower avalanche path toe, they could have climbed up the drainage via a route that was perfectly safe during NE instability of the type that existed during their day. This is a route where they might have stood and watched in awe as they triggered the same avalanche that would have otherwise ended up killing them. In my opinion, if the group had taken this route it is likely they’d all still be alive.

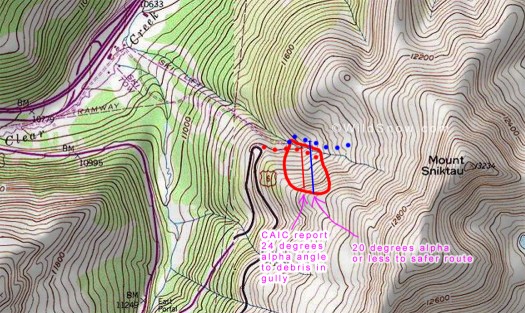

Google sat-map of Sheep Creek avalanche area, click to enlarge. The 'access' trail from parking is about 200 yards and while dangerous can easily be done one-at-a-time since it's slightly downhill. When you exit the access trail, you are exposed to the slide that killed the men, but only for a moment if you keep moving northeast and use the route I marked with blue dots. Mapping illustrates what a dangerous zone this is, with numerous avalanche paths and even previous avalanche deaths nearby.

What you see when you exit the approach trail. Much safer route is to left. Obvious avalanche slope to right. Click to enlarge.

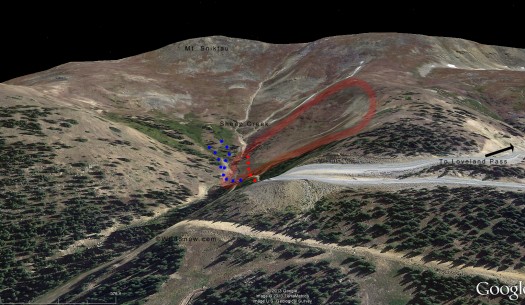

Touring up the safer route in Sheep Creek near Loveland Pass. Move a few feet to the right and you're in danger. Arrows mark known and obvious possible avalanche path, red solid line outlines 2013 avalanche, red dots are group's approximate route. Reports indicate they may have thought the grove of trees was an island of safety. Perhaps to some degree, but where would they have been planning on heading from there?

Looking northwest towards trailhead from safe route (blue dots). Reaching safer route still requires exposure to the avalanche slopes above the access path, as well as a short quick crossing of 2013 runout zone as shown in photos. Thus, during a lower hazard day this is all manageable, yet difficult or impossible to deal with on a high hazard day with large group. Burial sites are located from lower area near blue route all the way up out of the photo near small grove of trees, indicating the group was spread out, but even so were all on the same slope and same danger zone simultaneously, perhaps a severe error in judgment or perhaps many (or all) in the group simply did not know they were in danger. Latter theory could very well be true, as none of the deceased had used their airbags or Avalungs. In fact, the individual with the airbag still had the trigger handle zipped up in its compartment. Click images to enlarge.

Topographic view. Solid red line is approximate location of fatal 2013 avalanche. Red dotted line is fatal route. Dotted blue line is the safer route choice. Click to enlarge.

Another topographic view showing selected alpha angles of Sheep Creek avalanche at Loveland Pass. Many factors influence how far an avalanche will go. In the case of Sheep Creek a fairly deep gully actually makes it safer IF you are on the GOOD side of the gully. In other words, topography can increase or decrease the distance a slab avalanche will flow. Thus, once you're on the safer route as shown on map, you could be quite safe. One interesting thing to note is that once the gully has been filled by an avalanche, if another occurred it might jump the gully and flow farther -- but it does have to go uphill once it's past the gully. A slide with this small a drop doesn't have the energy to go uphill more than a small distance. In any case, due to favorable topography the safer route can easily be moved over to a 19 degree alpha angle zone or even less, for what most people would call a 99.99% safe route.

Google Earth tilted view of Loveland Pass Sheep Creek, looking southerly. Approximate avalanche boundary marked with pale red, red dots are route of accident group, blue dots are safer route accessing lower angled shoulder area with opposite exposure.

Thus, now that we’ve visited the site and actually done the same or similar tour to what the group must have been intending (giving them benefit of the doubt), it is quite easy to know where they erred. We may never know the why, though my intuition continues to tell me this was a simple case of a big disjointed group that failed in doing good tight decision making perhaps combined with a flawed terrain evaluation — only they had no margin for error. A situation I’ve been close to many times and know well.

1. As soon as you park, you’re in an area with avalanche danger in nearly every direction, next to a nearby slope where two skiers died in 1948. This proximate danger would have been obvious to most of the people in the group, or perhaps all, since there was a least some level of avalanche awareness and education.

2. If you did make it safely along the short but avalanche exposed access trail, by simply dropping ten or fifteen vertical feet and crossing a gully you can access a much safer route up the drainage, a route that quickly becomes 100% safe from the avalanche that caused the accident. For a group with this much experience, doing so would have been trivial. Why they did not do this and instead forged their way up their deadly route is mystifying. The route choice is totally obvious to the experienced eye, and the avalanche slope that killed them is totally obvious as is the extent it can run.

3. A 6 person group is too big for fine-grained contributory decision making, and the individuals were not spread apart to any significant degree. Even yesterday, my companion and I easily spread by a hundred feet or more on the access trail, and continued to do so when we got into the burial area which was somewhat threatened by new wind loading.

In summary, yes, we’ve all pushed the limits and made mistakes. But this was an unusual combination of numerous mistakes in a situation that was totally unforgiving of _any_ error. It is my hope and opinion that most experienced backcountry skiers would have recognized the severity of this situation and not even left the inside of their car, or at the least made substantial effort to mitigate danger by traveling in a small group, spreading out several hundred feet, and taking the obviously safer route once past the access traverse trail. But who knows for sure?

Whatever the case, I firmly believe that by documenting this tragedy and using it as a mirror, we can all significantly improve our avalanche safety decision skills. Indeed, I’d recommend that avalanche safety curriculum would heavily document this accident and use it as a decision making scenario — starting at the party the night before, leading to a parking lot meeting between a number of strangers, and on through stepping out of your car while looking at an avalanche slope thirty feet away that you don’t need a snowpit to rate as considerable hazard or worse. And that’s not even the slope that’s going to get you.

Skiing safe zone east of the avalanche accident site. This may have been where the victims were intending to go. Problem with that theory is if they'd continued up their route on the avalanche slope they would have just ended up on and under more avalanche slopes. Hence, there is a mysterious aspect to the accident we may never know the final answer for. Perhaps Jerome Boulay, the lone survivor, knows why they were in such an odd situation. At this time I don't feel comfortable pestering the man, but perhaps he'll eventually speak up, yet in his own time. The terrain and skiing in the safe zone is quite nice, but not particularly exciting. I liked it but would only come here during spring corn season due to the tricky access route. Plenty of other, better options exist off Highway 6.

In closing, we saw some incredibly stupid sight seeing activity at the accident site. We don’t recommend going in there unless avalanche danger is minimal or you have top notch evaluation and route finding skills.

Colorado Avalanche Information Center official report.

Annotated version of CAIC report.

Statement from first responder on the rescue.

Our first report about the accident.

(Note, Joe Risi contributed to the photography in this post.)

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.