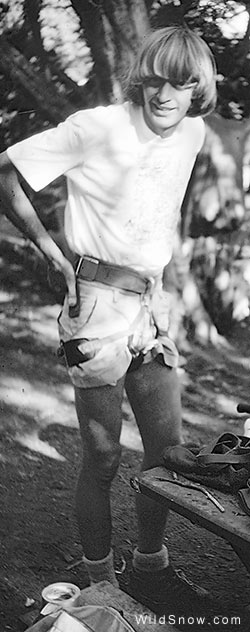

Rich Jack ski touring out of Crested Butte in 1980.

As you progress through middle age, you frequently loose touch with the friends of your youth. Nonetheless, most of us can easily harken back and relive those various adventures we had with our compadres during “the day.”

Rich Jack was one such friend. On June 26th of this year Rich died in a highway accident after a well lived life of 62 years. He was out adventure motorcycling and hit a deer near Steamboat Springs — no doubt on his way home from a glorious roam around the west he loved so much.

I had not seen Rich in quite a few years, and didn’t know he’d gotten into moto, but I’m not surprised. He loved adventure that involved technical problem solving combined with physical skill, and for many years fed his spirit with climbing, until health problems forced him to quit and do something easier on the body, (or at least on the feet, which is apparently where his problem was).

Rewind to Aspen 1971, which is where Rich moved after days as a high school ski racer out of Minnesota — a young buck who’d been initiated to real mountains during race training in Montana.

Rich was a well known figure around Aspen in those days. He wore his thick blond hair long, and at 6 foot 4 inches towered in height above most other guys. He was active in the ski shop employee culture, and spent winters cranking out turns with the relatively cheap Aspen season pass you could get back then. That is, he focused on skiing until he met rock and ice climber Steve Shea, who was another shop rat at the time. Due to his towering height and slim build, Rich was a natural climber and after being initiated by Shea into the climbing arts soon became part of our small crew of Aspen area rock and ice jocks. That’s how we met, as climbers, which began a frequent partnership that resulted in fine adventures that still bring a smile to my face.

The first big adventure was our freshman El Cap route in Yosemite Valley. We’d both done quite a bit of rock climbing by then, including shorter wall climbs, but tackling the big stone of Yosemite was how you took it to a new level. We were excited, ready, and no doubt somewhat clueless (though we did have good mentors and lots of training). Yet beyond training and gear the key to big wall climbing is your head game. I felt like we were on that as well, but something had happened that spring to Rich that could have destroyed his mental game, so the psychological factor could have gone either way and I think we both knew that.

That spring of 1973, Rich and his climbing partner Pete Williams were hiking out from a climb (Leaning Tower). They encountered a swollen stream and decided Rich would belay Pete across. As things can easily do when you combine ropes with stream crossings, it all went wrong and Pete drowned with Rich looking on and helpless to intervene. A lesser man would have given up the mountain life after that, or else dropped into denial and just climbed harder. Instead, Rich embraced climbing but became much more cautious and organized in his approach. More, he also developed a passion for helping others which manifested in his getting medical training and eventually working as an EMT, which ultimately led to his career in nursing.

Thus, Rich not only had come up with the idea for us to tackle Dihedral Wall that fall, but he also ended up being the voice of caution that reigned in the sometimes over-exuberant risk taking I was fond of at the time. Bear in mind that El Capitan routes such as Dihedral are now regarded as rather trivial endeavors. But in 1973 ‘The Captain’ had received its first ascent only 15 years before, and modern wall climbing techniques were still very much in the experimental stage. The climb went relatively flawless, though as anyone new to big wall climbing can testify, things such as hauling our baggage up a cliff would at times turn the day into a vertical circus.

Just imagine, you’ve got this huge bag of water and gear that you can’t carry on your back and have to raise with a rope. As you raise the bag, It gets caught under every overhang and lip. The guy above yards on a pulley system, while the climber below tries to jerk and heave on a trail rope to get the ‘pig’ unstuck. Sometimes the hauling can take longer than the climbing. Lucky for us, before the climb Rich had the idea of making a heavy duty fabric sheath for our haul bag. The bag itself was primitive, with various straps and buckles that could have caught everywhere and made the work even harder. Rich’s sheath covered all that stuff up, made the outside of the bag smooth, and was thus a big part in making our climb a success.

Rich and I continued to partner up after that, with scores of days spent cragging around the country with the occasional big-wall mixed in. We’d both gotten pretty good at wall climbing by then. Throughout it all, ever the cautious one, Rich was indeed the perfect counterpart.

In 1975, Rich (who unlike me was thinking more than 24 hours ahead) came up with the idea of doing a new route on the Diamond on Longs Peak, a fairly good sized alpine wall on a 14,000 foot peak here in Colorado. At the time, the Diamond had large unclimbed sections. We’d had a taste of how fun it is to do new routes while putting lines up outside of Aspen. We both liked the challenge of ‘new routing,’ the creative outlet couldn’t be denied, and we didn’t mind seeing our names in a guidebook either (the latter of which seems like a somewhat stupid motivation until you realize it did help with dating, and Rich was no stranger to chasing girls).

I remember the Dawson/Jack route well. We did the brutal approach hike to the wall, where Rich had spotted a crack system that looked promising. If I recall correctly, we climbed a few short pitches to reach the base of an obvious seam that looked quite difficult and dangerous. Rich and I knew our strengths as climbers, so without a word he set up a solid belay while I racked up for what became my first pitch of A5 (meaning I had to hang on gear that was poorly anchored, and could quite possibly have fallen several hundred feet). To this day, I clearly remember looking down at Rich belaying me, and feeling his care, strength and confidence running up the rope. I also remember knocking off a flake of rock that fell well clear of Rich, that is until it took flight due to its shape and did the perfect curve to make a direct hit on Rich’s helmet with a resounding POP. Yes, we wore a helmet for belaying — Rich’s idea.

Rich and I climbed together quite a bit over the next few years and remained fast friends. We did some road trips and lots of local cragging. Waterfall ice climbing was also in the picture, with Rich providing his signature solidarity to that endeavor as well.

In 1977 I was skiing backcountry near Aspen and badly broke my left leg. Having never been injured and being my younger arrogant self, I didn’t take care of myself and the leg healed incorrectly. I needed help. Enter Rich and his then wife.

Rich had become more involved in the medical professions, and met a nurse at Aspen Valley Hospital named Sandy. The pair got married (which sadly didn’t last). While I wasn’t climbing because of my messed up leg, I was still spending quite a bit of time with Rich (a lot of partying I shouldn’t have been doing) and thus had gotten to know Sandy. I wasn’t doing well at all. Depression was blocking any motivation to heal, so I was simply existing day-to-day in a bleak vacuum.

Rich and Sandy, bless their hearts, came up with the idea of me seeing an orthopedic surgeon named Dr. Boettcher who Sandy had worked for in Seattle. She’d assisted Boettcher with numerous surgeries, and vouched for him being a genius. More, Sandy’s parents lived in Seattle and she and Rich convinced them to take me in as a border, for free, for months of recovery time so I’d have a healthy place to live (and in retrospect, they were probably conniving to get me away from the Aspen party scene, and jolt myself out of the doldrums). Everything worked out as planned. To this day, I owe Rich and Sandy a deep debt of gratitude for getting me back on my feet when I was too much of an idiot to do it myself.

Rich Jack in 1981

Well, climbers we were before I got injured, and climbers we were after. So once the Jacks and Dr. Boettcher got my wheel working, Rich cooked up another scheme. The year was 1981. We’d skedaddle down to the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River, where a trio of hardcores had recently put up a cutting edge route they’d dubbed the Hallucinogen Wall. Due to an aura of mystery the Hallucinogen had not yet been repeated. It was rumored that the first ascensionists of the route had done part of it while stoned on psychedelic drugs, and thus accomplished inhuman feats of balance and strength. We were positioned to bag the second ascent, which, while not a first, is a pretty cool thing for a route of that magnitude.

As was our big wall style by then, the Hallucinogen went fairly smoothly for Rich and I. But at the same time it was easily one of the toughest things we’d tackled. The route had two cruxes, one for Rich and one for me. Well, actually two for Rich and only one for me.

A band of overhanging punky dirt-like rock splits the route. The first guys up there had manged to drive in a piton and move, or perhaps levitate, past that challenge. In doing so they’d beat up the crack to the point where Rich couldn’t get anything to hold his weight. He’d bash something in, we’d test, it would pull out. A couple of times he thought he had it, stepped up high, and took a fairly violent fall when the piece popped. This went on for four or five hours. We finally decided to try and drill a hole for an expansion bolt, which worked but was still marginal and scary. That was Rich’s first crux.

Next, Rich was up on another pitch and the piece he was standing on popped while he had his finger through the eye of a piton above him. Snap, broken finger. As a result he had to do the last two days of the climb with his hurting digit splinted by a banana sized wrap of athletic tape. He was in a lot of pain, especially during our last night on the wall, but he toughed it out and was always proud of us being the duo who took some of the scary aura away from that route by doing the 2nd ascent.

Oh, and the crux for me? What at the time they were calling the ‘hook pitch,’ another scary A5 gem. Yeah, it was my lead, but without solid and encouraging Rich down there belaying I never could have done it.

Along with all our wall climbing and cragging, we also did some alpine climbing together, such as the first ascent of a nice three pitch 5.9 route on the granite of the Williams Mountains east of Aspen (east face of Peak 13,203). Even though that’s a tiny non-descript peak, the route we did sticks in my mind just because of its remote and improbable place. Cool to have a line there that Rich and I put up, and I’m happy to admit it was mostly, or perhaps all Rich’s idea.

Another thing about Rich as a climber was he had a good sense of humor and was able to laugh at himself. One of his ongoing jokes arose because he was indeed quite a bit more cautious than I and some others in the climbing community, and during scary moves while leading he’d loudly speak the word “whoa,” only in a sort of extended version as in “whoooooa…,” enhanced with a warble. After a while, Rich started interjecting the same “whoooooa” into his recounting stories of hard leads, and would also cut loose with a loud “whooooa” while on easier pitches, as a joke.

During the summer of 1980, Rich and I discovered the part of mountaineering we were not that good at. But it was fun anyway.

Both of us had been doing quite a bit of alpine climbing by then, and we were well seasoned on waterfall ice. The peaks of the Andes loomed in our minds so we decided to go. We ended up in Huaraz Peru and tried to reach a peak Rich and I had somehow picked out of the thousands you can do down there. It was a beautiful mountain. I wished we’d seen it. Instead, our burro drivers and local “guide” led us on a four day snipe hunt, and we ended up several drainages over from our intended. Since that didn’t work out we decided to try something easy and headed for Huascaran, Peru’s highest peak at 22,205 feet.

Huascaran honestly could have been somewhat of a cruise considering our technical climbing skills and fitness, but we blew it by going too high too fast (something young fit guys have a tendency to do). We then sat in our tent for three days in a storm at nearly 16,000 feet, sick from the altitude. Gigantic avalanches roared down from above, our only defense being a huge crevasse that the ‘lanches fell into before they reached us. Rich had done too good a job with the medical kit, and delving into his large stash of Seconal to help sleep through the avalanches just made the altitude problems worse, and as I know now, could have killed me. With the weather bad and both of us feeling like half drowned dogs, we retreated.

Ok, how to salvage that trip? Rich and I were also skiers. By now we were both living in Crested Butte and had done a ton of ski mountaineering around there and in the Aspen area. So along with our plan for Andean summits, we figured we’d spend at least a month in Portillo, Chile riding the lifts as well as hiking for turns. That’s when the trip got good.

I could write a book about our Portillo stint. One highlight was when we ran out of money and lived in a snow cave near the hotel entrance for about a week. The staff called us the ‘eskimales,’ and the owner finally kicked us out, probably after he found out we’d been stealing diesel from the hotel generator tank to use in our MSR stove. We moved across the street to the brothel where the rooms were cheap. For some reason that was unpleasant, so we moved once again to the miserable bunk room in the train station where you slept sardined like Londoners in an air raid shelter during the blitz. The powder was good so none of that mattered.

What matters is I still have Rich’s ski bag from that trip, with his name on it (it’s the big red one in our Denali blog posts), and every time I use it the memories soar like feathers in the wind. What a fine individual. I know he will be missed.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.