Part of the equation of finding solace in the hills is reliable gear: an essential piece is the ski touring binding.

Welcome to the world of tech bindings. The emerging backcountry skier should be informed; it makes the conversation between you and the salesperson two-way rather than one-way. And, you’ll know what questions to ask to secure a product suited for you.

(We list a variety of bindings here, by intention, we limited our selection to what we feel is best considered by newcomers to the sport, considering factors such as availability, standardization, not a first-year product, and more. Suggestions welcome. This post comes as a partnership with our publishing partner Cripple Creek Backcountry.

This is an updated version of a story originally posted in August 2017.

See our ski touring glossary for lots of terminology — might as well start developing your ski touring language skills.

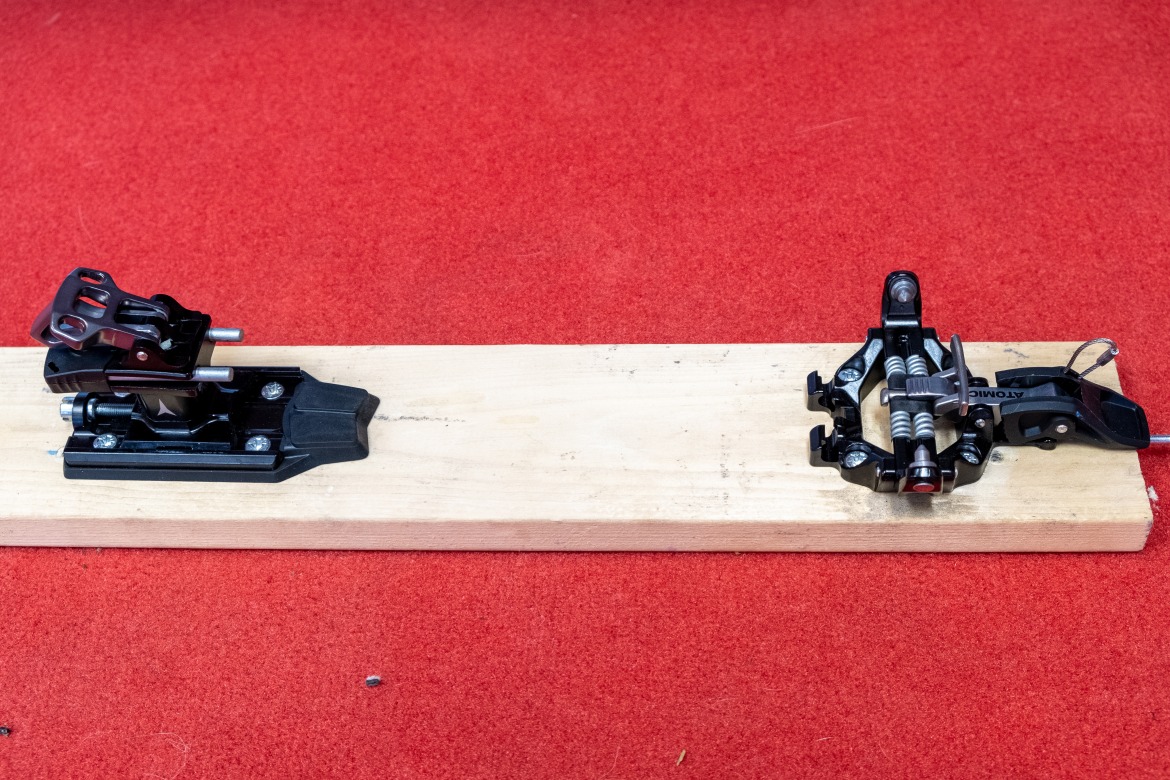

The Marker F12 EPF platform binding. In this case, the platform carries the binding’s toe and heel units on a frame (a.k.a., plate). It’s heavier than a pure tech binding, but still provides the ability to tour uphill.

The Atomic Backland Tour binding is a lighter weight tech specific binding. Note the toe and heel units are separate, making for a lighter overall binding system.

1. Know the difference between a “frame” and a “tech” binding. The frame binding carries the binding’s toe and heel units on a frame (a.k.a., plate); the frame, in turn, has a front pivot that provides walking action. You unlatch the frame for walking and latch it down for making ski turns.

Tech bindings, often called “Dynafit” or “Low Tech” (after foundational brands of the industry,) substitute the boot for the binding frame. This little engineering tweak (eliminating the binding frame) revolutionized ski touring by making bindings significantly lighter in weight and making it unnecessary to lift the weight of the binding heel unit during each stride.

Further, tech bindings generally have a toe pivot point closer to your foot than frame bindings. This closer pivot point helps with walking stride ergonomics. While frame bindings may appear “safer” or “stronger” than tech bindings, in WildSnow’s estimation there is no functional difference in safety or durability in either category. (This assumes all bindings are properly adjusted and used.)

2. If you’re looking for a tech binding rig you can ski both on the resort, and backcountry, best stick with the “free touring” (our preferred term) or “freeride” class of bindings. Such bindings are available as both frame and tech.

Free-touring bindings are cleverly designed with cosmetics or additional parts that may appear more substantial than lighter-weight binding versions. Still, in reality, their two main distinguishing features are a:) they boast ski brakes, and b:) some means whereby the binding absorbs ski flex with a spring-loaded mechanism that allows the heel unit to move forward and back on a track.

A few free-touring tech bindings also offer additional upward heel elasticity (part of the release-retention system), as well as a rotation feature. Such features are valid if you ski aggressively but not a deal maker or breaker for most of us. We’ve done quite a bit of writing about these issues; for edification, see How Elastic is the Plastic? and this post with a good video showing how the binding and ski flex interact.

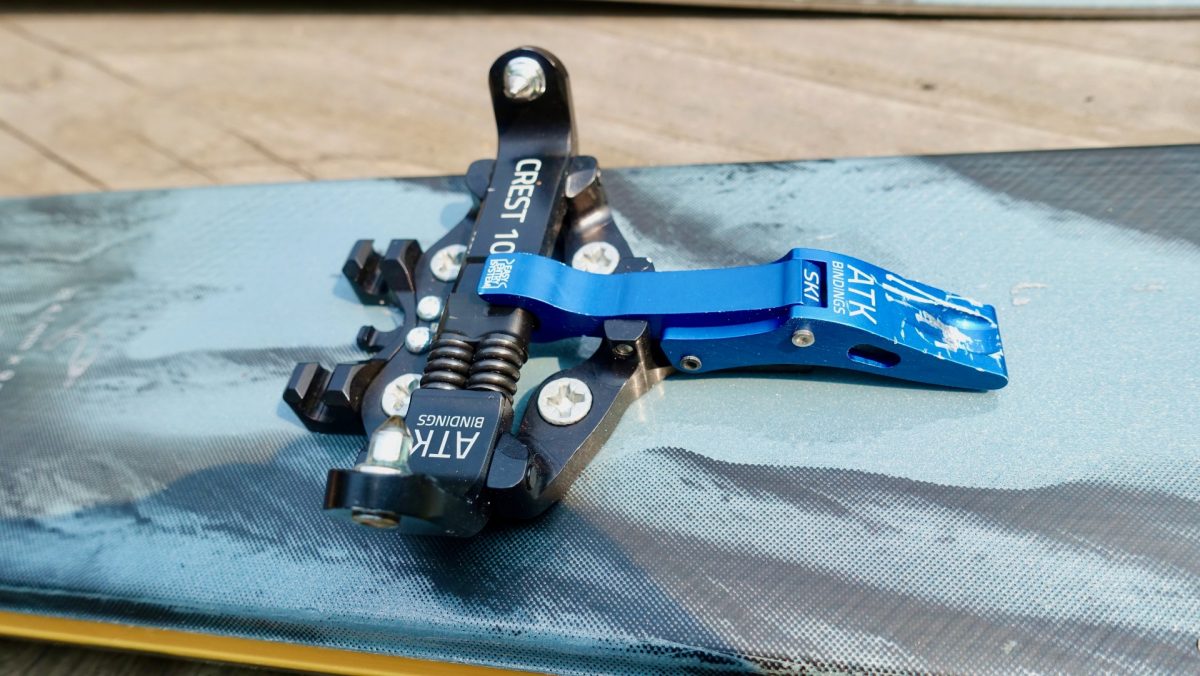

The ATK Freeraider 14 is a tech binding with features skewed towards skiers seeking a free ride oriented tech binding.

Examples of free-touring bindings:

ATK Freeraider 14 Alpine Touring Binding

Dynafit ST Rotation 14 Alpine Touring Binding

Salomon S/LAB Shift 13 Touring Binding

Fritschi Tecton 12 Touring Binding

Marker Kingpin 13 Alpine Touring Binding

Marker’s Kingpin, for example, boasts more heel upward travel in the release-retention mechanism you depend on while downhill skiing, the toe unit is virtually the same as most other tech bindings. We call this a “hybrid tech binding” as it uses the tech-type toe but an alpine-like heel.

(Scolding prevention: Some free touring bindings— notably Marker Kingpin— allow for significantly more vertical heel travel in the retention-release mechanism than most tech bindings. This only affects binding performance in downhill mode. Depending on your style of downhill skiing, this can be quite beneficial (for the hard charger) — or a non-issue. My view is nobody, no one, not anybody, should ski tech bindings as aggressively and carefree as they would an alpine binding. Learn to dial it back a little bit, minimize falling, and be aware of the consequences of an accidental release, i.e., getting pitched into trees at high speed or launched down steep terrain. This dire take is changing with the rapid pace of binding innovation — but I’m telling it like it is, not living in the future.)

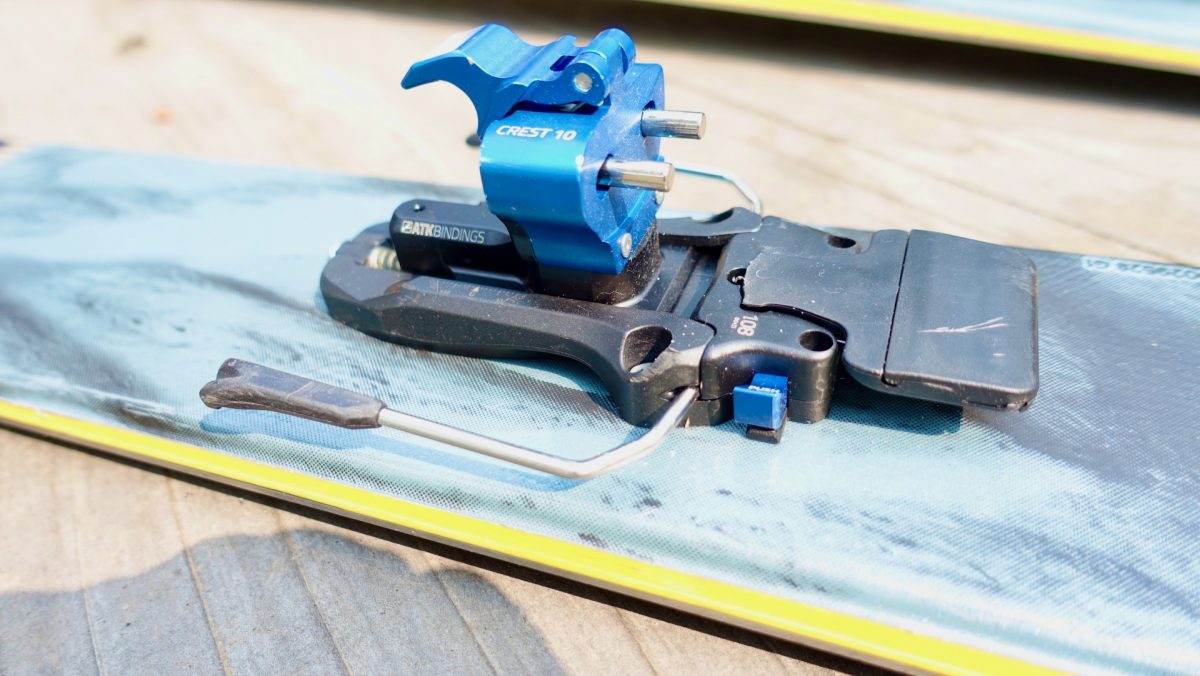

The Salomon MTN binding (also branded as the Atomic Backland) exemplifies a modern ski touring binding. Brake is optional and works well if you prefer.

3. Know that any free-touring binding can tour, but touring bindings without brakes and built to be lighter are not free-touring bindings. If you expect all or nearly all of your use will be for muscle-powered ski touring, pivot to the “true” touring bindings. Some of these have optional brakes, some have no available brakes. Some have mechanical ski curve compensation, while others depend on the rear “pins” sliding in and out of your boot heel fitting. In our experience, most users find that a properly adjusted binding of either type works fine for human-powered touring, albeit the free-touring oriented bindings are often noticeably heavier.

Caveat: If you fall and trigger a binding release more than a few times a year or are simply more comfortable with ski brakes, by all means, purchase bindings with brakes. Going “brakeless” isn’t for everyone — on or off the resort slopes.

The ATK Crest 10 toe unit is simple in design and reliable in function. The crampon slot is detachable. The Crest 10 is a no nonsense binding for lightweight ski touring.

The heel unit of the Crest 10 features adjustable lateral and vertical retention and an easy to use single button to activate the breaks for descending.

Examples of “true” touring bindings:

Atomic Backland/Salomon MTN: Has what, in our opinion, is the most well-designed ski brake on a tech binding. The brake is optional.

Dynafit Speed Radical Binding: this binding has been around in various iterations for years. The Speed Radical allows for 25mm of heel adjustment and three riser levels. This is a time-tested workhorse.

ATK Crest 10 Binding: This gem from Italy lowers into the sub-300g class, a 20mm heel adjustment plate, and three risers heights.

4. Enjoy your baseball stats, but don’t get caught in the ski binding numbers hype. In almost every case, the “12” or “13” versions of bindings are virtually the same things as the “10” versions. They’re often no beefier; any mechanical differences are trivial. They won’t make you ski better. The only difference is that larger or more aggressive skiers can indeed dial up more release-retention force with the higher numbered version.

You’re immediately thinking: “That’s me! I’m aggressive; see that number on my bindings?”

Avoid mental shenanigans. Nearly every ski tourer out there will be fine at settings based on standard “DIN” charts, meaning even if you need a few “notches” over chart settings, a “10” binding will do you fine. If you’re the exception, you know who you are and probably don’t need these shopping tips.

5. Avoid first-year tech bindings. It pains me to write this. I like new gadgetry as much as the next guy. But the history of tech bindings shows what I feel is an excessive number of defective products that don’t become known until they’ve been in “consumer” testing for a season (or more). So buy what’s been around for a season or two. The prices might be better anyway.

6. Buy your bindings from a reputable retailer that services the ski touring market. If possible, get your bindings mounted there as well, especially if a DIY mount causes high anxiety. But trust no one. Upon first receiving your mounted bindings, immediately snap your boots into the toes and ensure the boot heel fitting falls on the heel pins. Also, inspect the binding base plates — they should be snug to the ski. Perform an on-the-bench function test with your boots, and after that, do a “carpet test” involving you in your boots, entering and exiting the bindings on the floor.

7. Following along #6, in the case of most tech bindings you must learn how to check and, if necessary, adjust your binding “heel tech gap” and your release-retention settings. Tech gap requires various methods and settings by brand and model, we have lots of how-to posts here at WildSnow, and most bindings have some sort of manual that describes the procedure.

Heel gap refers to the spacing (read gap) between the boot heel and the binding heel unit.

8. But, and it’s a big BUT, if you do ski out of a binding, before fooling around with your release settings, be sure you have a good guess as to why you took your (hopefully) brief flight.

Assuming your bindings are set to a reasonable retention level, most accidental tech binding releases are caused by icy or dirty boot toe sockets, ice under the toe wings, or misadjusted heel gap . IMPORTANT, cranking up your release value setting without knowing truly “why,” you threw a shoe could result in a broken leg or destroyed knee.

9. Don’t assume your bindings are ready to go every time you extract your skis from your rooftop box. Referencing what I wrote above, inspect your bindings often for impending breakage or missing parts. Past lessons we’ve learned: Brake “pedal” plates that go AWOL, screws in the heel unit that begin to back out, cracks in the toe unit frame (super dangerous), broken heel lifters, and other nightmares too numerous to list.

10. In the tech binding world, sometimes, a specific boot-binding combination simply does not function. A common example is a boot-binding combo that doesn’t exhibit smooth release on the bench or deliver reliable downhill skiing performance without accidental release. A less common concern but something to consider: tech bindings are not for everyone. This is especially true if you’re attempting to push your bindings to perform on-resort as alpine bindings. At the least, Check your bindings with basic bench top moves you can do at home.

A last note: I’ve encountered individuals who were not willing to commit to tech binding idiosyncrasies such as ice cleaning, greater possibilities of breakage, finicky adjustments such as heel gap, sensitive release settings, and so forth. If you fit that category, and use your bindings mostly in-resort, sans muscle power, consider a frame binding that mimics an alpine binding (Marker Duke). Or, simply ski alpine gear when you’re lift-served, and ski touring gear when you’re muscle powered.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.