Avalanche Peak: Avalanche Peak, in the Esplanade Range north of Golden, BC, delivers less complex terrain, but not without some hazard on the wrong day.

“If you don’t want to experience crime, and you see crime happening down an alley … don’t walk down that alley!”

Wiser words have never escaped the lips of a human, and in this case, the wise Nick Vincent uttered this dictum during an avalanche course in Leadville, Colorado.

So simple … yet sometimes so difficult for the pow-obsessed, fun-hog, snow-sliding crowd of which you and I are dedicated members. We love to ski and ride untracked slopes, and many of those slopes are avalanche prone.

So why not just avoid them entirely?

Abstinence

As Nick’s words suggest, total avoidance – or dear god, abstinence – is the most effective antidote to most hazards, but how realistic is that for us? If we avoided avy terrain altogether, our options would be 55-degree couloirs and 22-degree meadows far from overhead hazards.

Most of us choose to recreate in areas where we know avalanches occur at certain times. Abstinence isn’t any more realistic for us than it is as a sex-ed strategy for most high schoolers. The trick becomes picking our days and knowing when it’s OK to expose ourselves to the hazard.

In short, it’s all about minimizing or eliminating exposure (to avalanche terrain) when it’s appropriate. Just as you can walk down that alley during broad daylight, you can recreate responsibly in avalanche terrain by dialing up or down the exposure knob.

Most of us probably already know this – if you’re not in or under avalanche terrain, you can’t get killed by an avalanche. Others formulations exist: “If snowpack is the problem, then terrain is the answer.” Or, “Ski as if you’re not wearing a beacon.”

No matter how you put it, the sentiment is the same: minimize exposure to minimize the chances of getting smoked in an avalanche-dialing back the exposure knob!

The What?

I don’t recall where I first saw it, but I remember an explanation of risk assessment using four components: likelihood, vulnerability, consequence, and exposure. For me, it made great sense, a light-bulb moment.

Likelihood: How probable is it that the event occurs? Will we trigger an avalanche on this slope if we ski it? An accurate answer would be the end-all data point in backcountry skiing, but anyone telling you with total certainty that one slope will slide while another will not is vastly overconfident, a con man, or a lunatic. Sure, we can judge quite accurately on low- and high-danger days, but most people get killed on moderate and considerable days. Judging likelihood on those days is very, very difficult with any real precision.

Riders obsessed with pit scores and taps and digging are managing the hazard with the likelihood knob.

Vulnerability: How vulnerable are our frail, puny bodies to avalanches? We score avalanches on a scale from 1 to 5, and a size 2 is enough to “bury, injure, or kill a person,” so, sure, it seems like we are darn vulnerable to being injured or killed in avalanches.

We tweak the vulnerability knob by wearing a transceiver, an Avalung, and perhaps an airbag – but in the end, even with all the latest gear, we are still vulnerable to avalanches. Not much help here.

Consequences: What happens if we get avalanched in a particular spot we’re considering skiing? Are we above cliffs or a crevasse? A creek? Bare rock and ground? A nice, gradual apron that ends in a meadow? Consequences can be more straightforward to assess, but again – people get killed in small avalanches in relatively benign terrain all the time, as it turns out.

It’s good to be paying attention to consequences and minimizing them when we can, but it’s a fool’s errand to assume that getting avalanched above a gentle runout is going to save us. Consequence knob? Dial it where you can, but it won’t keep you alive for long.

And that leaves Exposure. Are you in, or are you out, of avalanche terrain? Sure, people underestimate or even completely misidentify avalanche terrain. It happens all the time – but exposure, an accurate judgment of exposure, is our best defense against being impacted by a lethal avalanche.

If we had a dashboard with the word AVALANCHE in big letters above four dials – likelihood, vulnerability, consequence, and exposure – exposure would be the most effective knob to manipulate. Dial back the exposure; you dial back the avalanche hazard.

Upper Cheap Scotch: Now THAT is an avalanche! The deep slab awakens above Sorcerer Lodge, British Columbia. Relatively simple terrain, non-glaciated, and an obvious avalanche slope. With a deep persistent problem, zero exposure is the best call.

Exposure and ATES

The Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale (ATES) has become more well-known in the US over the last decade. ATES attaches a rating of “simple,” “challenging,” or “complex” to a ski itinerary (more on what this means in a sec.). Guidebooks, like the popular Beacon guides in Colorado and Washington, use an ATES rating.

Developed in Canada by Parks Canada, Grant Statham, and others, the ATES scale classifies zones and terrain so that we, as field practitioners, can have a shorthand idea of how difficult it is to manage our exposure.

Presented at the 2006 International Snow Science Workshop (ISSW), Statham, Parks Canada, the Canadian Avalanche Association, Bruce McMahon, and Ian Tomm explained: “Parks Canada has developed and implemented … (ATES), which provides a framework to comprehensively evaluate, describe and communicate the complexities of avalanche terrain exposure.”

Many of you may remember the tragic 2003 accident on Rogers Pass, British Columbia, involving children on a school-sponsored trip. Seventeen students were involved in a natural avalanche and seven died. (This event came just weeks after the infamous accident at a nearby ski operation where seven clients died in another avalanche, intensifying the media and public attention on avalanches in general.)

The Rogers Pass accident provoked a renewed effort to formally classify avalanche terrain, much like climbers and paddlers had done for decades. This system would be both a public and professional service. ATES grew from this effort, and by 2005, Parks Canada had given an ATES rating to nearly 300 ski tours and almost 100 ice climbs.

The Scale

Here I think it’s worth taking a quick detour, hopefully not into the weeds, but at least brushing past them!

Let’s consider the “scale” at which professionals apply the ATES. (Note: I’m not talking about the ‘s’ in ATES itself, but rather the scale at which the classifications — simple, challenging, complex — are applied.) This helps us understand not only how the model was developed, but also begins giving us a glimpse as to why the ATES can be so helpful.

When ATES arrived in the US, I witnessed and participated in several training exercises and avy courses during which participants would try to classify snapshots of slopes or drainages. This experience led to great discussions – sometimes heated! – about what qualified as “challenging” vs. “complex” terrain, for example.

After re-reading the paper linked above and working with/around ATES for some time, it’s helped me to revisit the particulars and recognize the scale at which Parks Canada and other contributors use ATES. The original authors wrote,

“The ATES was designed to classify ‘trips’ rather than individual pieces of avalanche terrain. This necessitated discussion regarding the boundaries of each trip, and highlighted how the link with published guidebook information is critical. Simply providing the public an ATES rating is not enough – they need to understand the details of each trip, including the boundaries of the region under discussion.”

Professionals use the term “operating zone” when posting information about their daily work, and this seems analogous to using the ATES – it’s more than just the “run you’re going to ski.” Rather, it encompasses a larger view; that is, where you’re operating on the day: the approach, uptrack, the down, your exit, and of course all the terrain to which you’re exposed or attached, too.

The Criteria

The ATES developers started with this more inclusive view of classifying terrain and then agreed upon the criteria by which the ATES would be decided. Along the way, they also recognized that the public and professionals would use the information in slightly different ways, and therefore, two parallel, but distinct systems would be necessary. The authors wrote, “Both models say the same thing, delivered in different languages.”

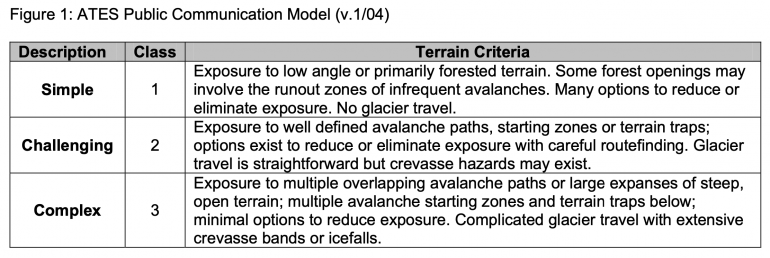

The ATES public model.

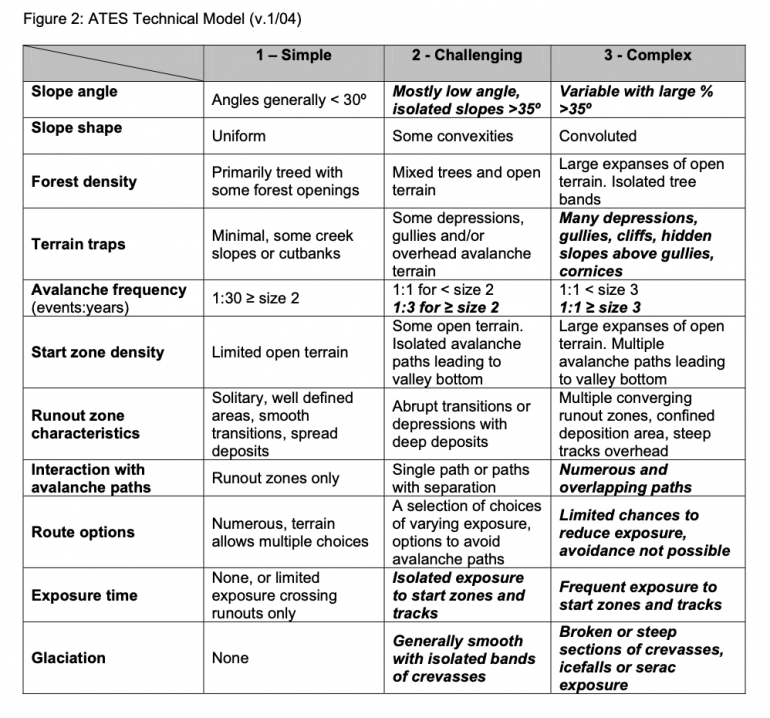

The ATES Professional Model.

I poached the two sets of criteria from the original paper and I encourage you to read the whole thing. If you compare the two, it’s easy to see the developers baked much of the professional information into the public version.

And so?

So, exposure, ATES, and us. Now what?!

Forgive me, I know this is a bit of a deep-dive into exposure, but I’m on a rest week before heading to Canada, so I’ve got the time to navel-gaze a bit.

Exposure motivates me to geek out a bit on the topic for two main reasons.

First, my experience leads me to believe that newer guides and backcountry skiers focus too much on likelihood. Take this with a grain of salt – my own experience certainly doesn’t speak for “the industry,” avalanche education, or even skiers in general. It’s just what I’ve seen.

I see too many people posting pit videos (trying to determine the chances of triggering an avalanche) and discussing likelihood, which just leaves too much uncertainty in the equation for me.

A sentence in the Statham paper jumped out at me and echoes my point, “Indeed, while snow stability evaluation is a critical input to decision making, it is avalanche terrain evaluation skills which provide the most security during complex decision-making situations.”

Second, I routinely see ATES being not quite understood in courses and in application. Rather than worry about whether a run or drainage is simple, challenging, or complex, the real discussion should be more about exposure. It’s a scale, right? Some terrain could be considered “simple-almost-challenging,” or “simple-plus.” The point is to recognize what features in the terrain increase complexity and exposure, not arriving at a name for it.

In the end, who cares? The real discussion is, are we comfortable with this much exposure, given the avalanche problems, what the weather’s doing, how our team is performing, and our mindset on the day?

Rather than debate test scores and skiing one at a time, a team might debate whether it’s reasonable to be exposed to the terrain at all.

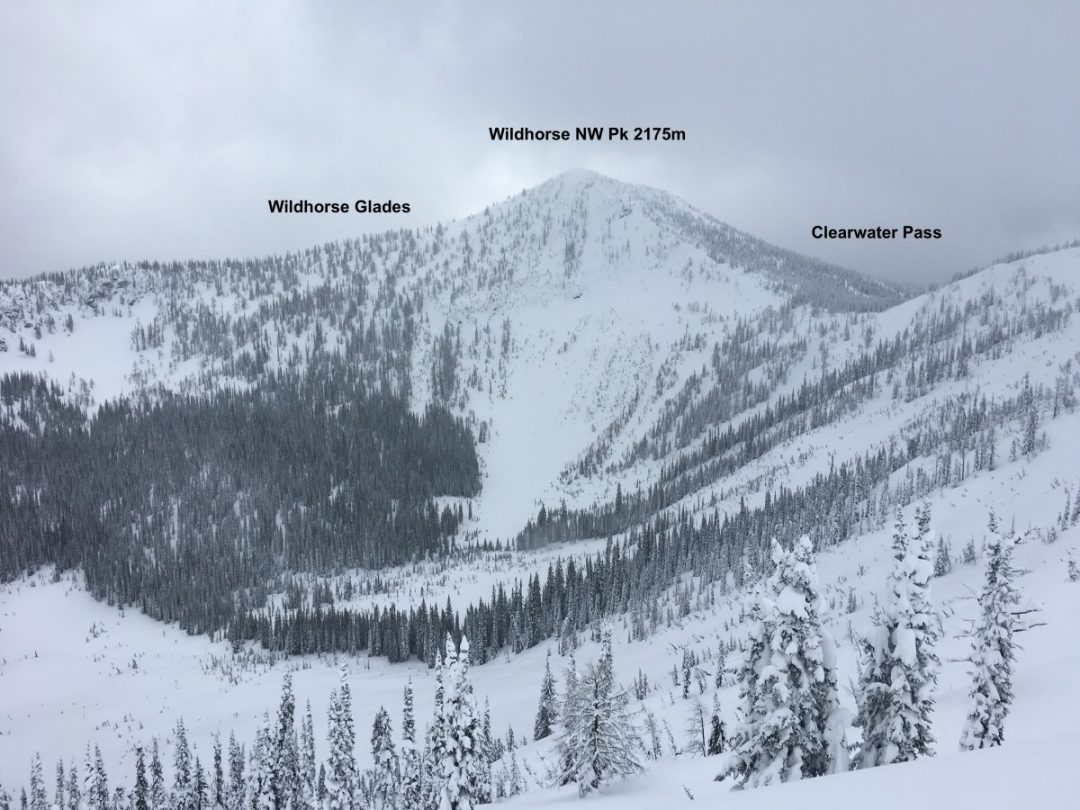

Wildhorse: Just south of Nelson, BC, Wildhorse Peak offers fantastic tree skiing, but careful routefinding required.

The Exposure Knob

So, next ski tour or decision-making point, try and view the hazard through the lens of likelihood, vulnerability, consequence, and exposure. And see if the exposure knob is the one you want to tweak.

Read, remember, and recognize the diagnostic criteria in the charts above. “Numerous and overlapping paths,” for example, appears in both bold and italics, meaning it carries more weight than others.

The authors write, “Terrain that qualifies under an italicized descriptor automatically defaults into that or a higher terrain class. Non-italicized descriptors carry less weight and will not trigger a default, but must be considered in combination with the other factors.”

To restate, if you see (on the map or with your eyeballs) numerous and overlapping avalanche paths, you are in complex terrain. By definition, this means fewer opportunities to limit exposure. With an isolated wind slab problem, maybe that’s tolerable to you, but with a deep-slab lurking … I’ll meet ya in the lodge or the hot tub!

Add these ATES characteristics to your observational “red flags.” Let them help you make simpler decisions on complex tours. On days with too much uncertainty or ones where you can’t reliably dial the likelihood, consequence, or vulnerability knobs enough to your liking, see about exposure.

The exposure knob is my best defense from that crime-ridden alley Nick mentioned. Dial yours back and live to tell the tale!

Rob Coppolillo is a mountain guide and writer, based on Vashon Island, in Puget Sound. He’s the author of The Ski Guide Manual.

Rob Coppolillo is a mountain guide and writer, based on Vashon Island, in Puget Sound. He’s the author of The Ski Guide Manual.