Big thanks to onX Backcountry for sponsoring this post. Plan your next adventure with 20% off your app subscription. Use the code WILDSNOW20 at checkout.

I’ll never forget my surprise at learning that the Wind River mountain range in Wyoming is home to the second largest concentration of remaining glaciers in the Lower 48 (Washington’s North Cascades take the prize). And unlike the stragglers in the high peaks of Colorado more akin to dormant snowfields than moving ice, the Wind River glaciers are fully featured — crevasses and gaping bergschrunds, moving ice swaths that continually shape the mountain landscape and provide ready water supply to the arid West. But, like all glaciers around the world, they are on the decline.

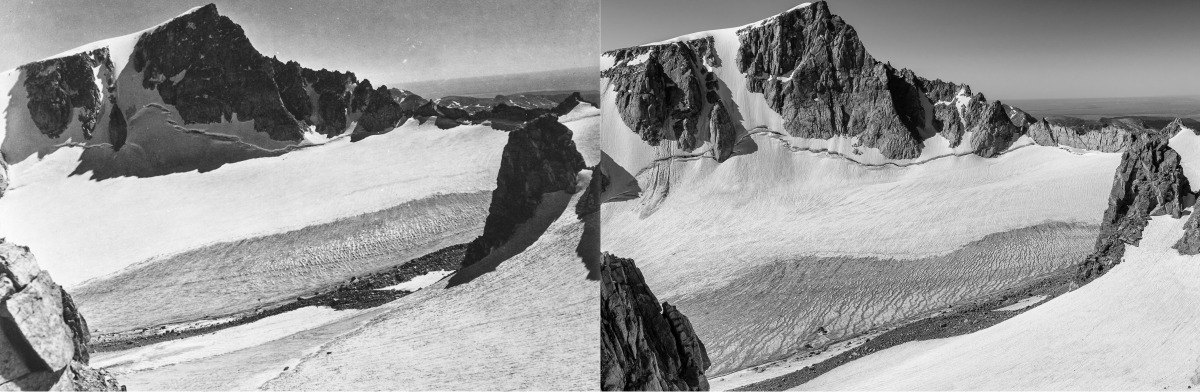

To capture their recession visually, Dr. Ed Sherline, an Associate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Wyoming is taking photographs. Not just photographs, but rephotographs, matching his images with those captured by the glaciologist Mark Meier, who originally documented Wind River ice in 1950.

Sherline has been visiting the Winds since 1979 and began his rephotography project last year. Having my own deep personal interest in both glaciers and the Winds, I called Ed up to talk about how he got involved in the project, challenges he’s faced along the way, and why rephotography is an especially helpful tool for illustrating climate change.

(Note: click on all photos to enlarge)

WS: Who was Mark Meier?

ES: He was an incredibly important glaciologist. He photographed the Winds for Master’s thesis at the University of Iowa, which he complete in 1951. From there, he went on to Cal Tech to get his Phd and worked for the USGS in Seattle and was one of the first people in the 80s to put together the connection between glacier melt and sea level rise. He was the director of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) at CU Boulder and died in 2012.

He also was an artist, which his photographs of the Winds show. He was doing them for documentary purposes but clearly had a photographic sensibility.

WS: How did you first become interested in repeating these photographs?

ES: The Wyoming Institute for Humanities Research have grants to work on a humanities style project. As I was thinking about trying to write and add photographs to the narrative of my sense of mourning for glaciers as they disappear, I came across Meier’s thesis. I thought, man, this is a pot of gold that’s just been handed to me. That’s when I realized I could do a rephotographic project.

He did a very systematic job of photographing the glaciers around the Fremont Peak and Gannett Peak regions. With his scientific eye he was careful to take photographs that would show off the specific attributes that glaciologists want to see about the glaciers. It’s worth noting that there have been other people who’ve tried to rephotograph the glaciers that Mark has. So this is no secret project or original to me.

I love landscape photography and making pretty pictures, but I also want to find ways to connect my photography to socially relevant issues. This was a way to do that.

WS: What time of year are you taking these photographs and how are you matching that timing with when the photographs were originally taken?

ES: There’s so much snow cover over the Winds and the glaciers that you have to wait until most of it melts off, that’s mid to late August or September before things shut down in the winter. It’s a pretty narrow window.

When Meier went, he was there for six weeks. He went in around the first of August and stayed until the second week of September. Nearly all of his photos are from a little later, mid-August to early-September, which is when I go.

Because I’m going by myself, I also like to time it when the crevasses are as open as they are going to be. I have stumbled on covered up ones even in late August but for the most part I feel like that’s the safest time to be traveling on the glaciers alone.

WS: Aside from timing, what else are you thinking about as you try to replicate the photographs? Where are you setting up your camera and situating yourself so you can get the closest match possible?

ES: I didn’t realize how hard that finding the same position was going to be until I was in there last year trying to actually do it. I start by studying his photographs. I print them out really big and high resolution so I can get lots of detail benchmarks. I map out on Gaia where I think he took them. But that only gets me so far.

Then it’s a matter of basically just wandering around with my camera and tripod, looking through it and trying to match things up with his photographs. That can take hours. Sometimes I’m on really loose moraines and scree fields. At times it’s not that hard. Some of his photos he took from summits but even there I thought I nailed a couple summit shots. When I looked at them on my computer I realized my tripod was maybe five or ten feet back too far.

I learned that I can figure out whether I’m too low or too high based on how many peaks are in the background. I’ll try to find boulders that are distinctive in his photos that I can try to find in mine. It’s really being very attentive to what you’re seeing around you. I’ve never paid so much attention to rocks in my life.

One thing that makes it really hard is that he took a lot of his photos not from bedrock positions which are generally pretty stable, but from the glaciers themselves or from the moraines around the glaciers. Those are fluid standpoints that are shifting. Over 70 years, the moraines have changed somewhat and the glaciers have definitely changed. So in some cases his exact standpoint is not going to be available because it’s no longer there.

WS: I noticed in some of the photographs, like Bull Lake glacier, it doesn’t look like the glacier has changed that much. To your knowledge, why is that?

ES: I’ll qualify this, since I’m not a glaciologist, I’m channeling Neil Humphrey who is the expert glaciologist at the University of Wyoming and a friend. He has looked at these photos and I’ll be hitting him up for more analysis.

The first thing that Neil would say is, well you’re looking at a comparison of photographs so this isn’t going to be precise. You’re not making the kind of careful measurements that they would use to identify glacier recession.

In some cases like Heap Steep glacier and Knife Point glacier, the recession is noticeable. According to Neil, Heap Steep is in this little cirque and has it’s own weather pattern in that area. Its recession is more due to the natural warming of climate after the Little Ice Age. Mark Meier was noticing some recession of the glaciers in 1950, based on his personal measurements and comparing moraines between where they were in the Little Ice Age and where they had retreated from that point. He was noticing recession in 1950, and there had been human caused climate change by then but the most significant temperature change happened after 1950.

For Heap Steep, Neil thinks most of the recession is due to natural warming after LIA, whereas on Knife Point glacier, the recession on that one is due to human-caused climate change. That was one of the biggest scientific lessons I realized: yeah, glaciers are receding but they’re not all receding at the same time or not necessarily the same cause.

WS: Why are these rephotography projects particularly useful?

ES: Glaciologists use rephotography of glaciers. They can see how the glaciers changed, whether it’s receding, expanding, perhaps its rate of recession. They can learn a lot about a glacier by comparing photos.

It also has a broader public value, because it dramatizes the impact of climate change. Photographs are a very visceral proof of it, in a way.

Another thing for me is to honor the glaciers and the landscape. It’s kind of a memorial to them. These glaciers aren’t going to be around that much longer, many are already what glaciologists call ‘dead’, which means they’ve gone from glaciers to permanent snowfields. You’ll still see snowfields in the summer but you wont get the dynamics of a glacier, the movement.

WS: Have you had any particularly surprising moments while doing this?

ES: One aha moment is when you’re walking across a lot of these glaciers, when you’re on the glacier, it’s wet. It’s melty and you’re postholing constantly and then you’re going through these huge glacier swamps. Early in the morning you might be walking on a nice crisp, hard surface but by midday you’re just slogging around in slush.

I also started investigating the names of the glaciers. When Meier did his project in 1950, a lot of the glaciers didn’t have official USGS designations, and that got me interested in how the glaciers and peaks around them got named. I was especially interested in Indian Pass which is the pass that he used to photograph Harrower Glacier from. That led me to the Mountain Shoshone, who used Indian Pass to connect from the eastern side of the range to the Western side. I hadn’t really thought about how the Winds themselves have been used and traveled in by people well before modern climbers and backpackers came in there. As part of this project I’m trying to learn more about the Shoshone and their relationship to the glaciers and the Winds.

WS: What’s next for the project? Will you head back up this summer?

Definitely in August. Meier took a lot of photographs of the glaciers that surround Gannett, so I plan to do that this summer. All of the photos I have so far are primarily of the glaciers that surround Fremont Peak. One of the cool things about this project is it takes me into places I’ve never been and into terrain and across routes that I don’t get from looking up any of the trails or guidebooks. It’s really fun.

See more of Ed Sherline’s rephotography photos here. Many of the images will also be heading to the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder to join the photographic archive of glaciers around the world. Find more of Meier’s photos on the Glaciers of the American West website.

Manasseh Franklin is a writer, editor and big fan of walking uphill. She has an MFA in creative nonfiction and environment and natural resources from the University of Wyoming and especially enjoys writing about glaciers. Find her other work in Alpinist, Adventure Journal, Rock and Ice, Aspen Sojourner, AFAR, Trail Runner and Western Confluence.