The Sparkr Mini is a worthy addition to your kit

Campfires have saved my life. More than once. Since constructing my first “survival kit” as a fresh faced Boy Scout, I’ve always carried fire starting items in my backcountry kit. Not much: a bit of tinder (lint balls soaked in petrol jelly), a pair of butane lighters, perhaps a flint sparker if I’m headed for multi-days in the boondocks. The butane lighters are the weak link, here’s why:

— Don’t work well when wet.

— Difficult to operate with cold numbed hands.

— May not work at all in the slightest wind.

— Tend to accidental triggering unless they’re secured with rubber bands and packed carefully.

— Hassle to refill, even if possible.

I’ve thus been intrigued by the evolution and ostensible improvement of lighters — especially the electrical ones that produce small plasma sparks and are easily activated with a button press. I acquired a Sparkr brand Mini of this persuasion and did a few tests.

Ignition test

Plasma lighters don’t produce a flame, just a small hot electrical arc. Thus, you can’t project the heat to tinder material as you can with a butane lighter or match. Instead, you have to shape the tinder material such that a bit of it fits between the lighter electrodes. For tinder, I carry dryer lint wadded up with petroleum jelly. No problem with ignition as the lint is easily pinched into a shape that the lighter can touch.

Using a urethane accessory strap for tinder is a standard backcountry fire starting trick. The Sparkr worked fine for this as I could slice off a chunk that was sized for the lighter, or ignite the edge of the strap. I found something interesting during this test: Not all plastic accessory straps ignite equally — one brand acted as if flame retardant. (I’d advise cutting a slice of material off the end of a strap and testing yourself.) Starting a fire with natural tinder such as small twigs could be difficult with a plasma lighter. In testing I found it necessary to use dry wood shavings, preferably from a conifer with sap content. That said, lighting a natural-tinder fire with a butane lighter or matches can also be a challenge. Conclusion: as always, carry your preferred artificial tinder.

Immersion test

This is where Sparkr plasma lighter shined compared to matches or butane lighters. I stuffed snow into the electrodes, blew it away with a breath, and the unit worked perfectly. Same thing with a splash of water. No problem with wind either.

Subarctic test

As with most electronic equipment, Sparkr is officially rated down to zero centigrade. And as with much electronic equipment, I had no doubt it would work at temperatures somewhat below that. But how low? I cold soaked the Sparkr in our chest freezer to negative 4 degrees Fahrenheit. With a fully charged battery the unit worked fine. With battery partially charged it soon died. That’s understandable, as rechargeable lithium-ion batteries loose lots of capacity when chilled. I don’t see this as a big deal. If you need the lighter during a cold day, put it in your pocket for ten minutes before use. On the other hand, I wouldn’t advise using the Sparkr plasma lighter in deep-cold environments such as Denali high camps (perhaps other plasma lighter brands or models have larger, or user replaceable batteries. Comments?

Other considerations

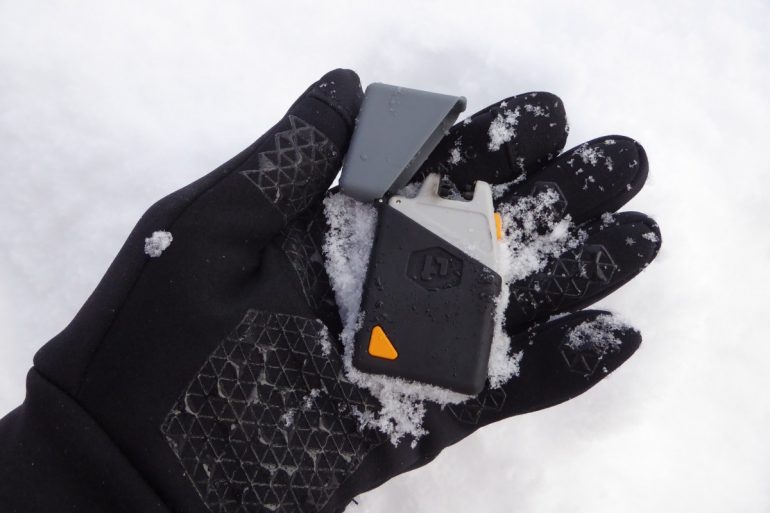

I like having a secondary light source in my repair/emergency kit, normally a mini-flashlight or something of that nature. Sparkr includes an LED light that’s invoked by pressing a button three times in succession, to prevent accidental switching. The button (yellow in photos above) is level with the unit’s housing, but accidental activation of the light could still occur in the dark, mysterious confines of your repair kit. So while I like the flashlight feature, I’m not convinced it’s a good thing. A bit of thin plastic taped over the button would probably secure it. (Most plasma lighters do not have flashlights; I tested Sparkr specifically because it does.) Accidental activation of the ignition element is virtually impossible. It has a safety lock that’s integrated with the hood, as well as the usual thumb button.

Conclusion

Plasma lighters are a viable addition to any fire starting kit, but as with any other flame source you should have at least one backup of a different type. As to the Sparkr specifically, it feels nice in the hand and tested well. If the flashlight doesn’t activate accidentally, then I’m happy with it. Note the limitations of lithium-ion rechargeable battery (cold sensitive, gradually looses charge while stored). Most “lighters,” be they butane, electrical or whatever, are of course designed for igniting cigarettes and things of that nature. In that sense, they’re not ideal for fire starting, but you work around the limitations in return for advantages such as easy ignition and wind resistance. As with all fire starting solutions, test at home. Also note that Li-ion batteries lose charge over time, so you’ll need to top off the charge now and then.

Specs for Sparkr, Mini model plasma lighter and flashlight

— Lithium-ion power 300 mAh: 3.7v (rechargeable via USB, sensitive to cold)

— Recharge source: micro USB

— Flashlight output: 25 lumens

— Weight: 42 grams

— Dimensions: 6.8x4x1.5 cm

— Specified operating temperature: 0-40 Centigrade (worked while cold soaked to negative 4 degrees Fahrenheit).

Amazon ran out of these, it appears they’re available on the Power Practical website. If not, then consider any of the hundreds of other plasma lighters available per our embedded Amazon links. Be sure to torture test at home, then add to your kit.

Commentators, please share suggestions for good quality plasma lighters that might work well for a repair-emergency kit.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.