Persistent weak layer + wet snow = historically massive avalanches

Unless you were living under a rock last winter, you likely heard about the rampant avalanches that funneled across the Colorado Rockies during the first half of March. Perhaps you spotted YouTube footage of a slide swallowing I70, or two snowmobilers out-gunning a massive snowcloud overtaking Maroon Creek Road near Aspen. Maybe you tried to travel Colorado State Highway 550 and found it was closed…for 18 days straight. Or you checked the avalanche forecast in hopes of harvesting some of the deep snow and found that not only your local zone, but several others were flashing black as though signaling certain death.

The fact is, no one alive had ever witnessed an avalanche cycle that big or destructive in Colorado. And while the 2018-19 winter itself wasn’t necessarily record breaking in terms of snowfall, it was unprecedented in its destruction. Colorado Avalanche Information Center Deputy Director Brian Lazar relayed the details to a fully packed house in the Cripple Creek Carbondale store on a balmy evening a couple of weeks ago. Here’s a brief recap of his talk.

Note: I’ve made an effort to highlight some of the major events and circumstances, but this is not a comprehensive list of all that transpired. Check out the CAIC website for additional details.

The trouble began, as mid-winter snowpack trouble often does, in October. Enough snow fell in the high country to linger through a relatively dry November until regular winter storm cycles started in earnest in December. The early snow left in its wake the dreaded persistent weak layer.

Fast forward to late February: each storm until that point had delivered just enough but not too much snow to poke at that weak bottom layer. CAIC forecasts held steady at moderate to considerable in most places. Colorado had a deep and consistent snow pack with an average of three meters rested atop that week layer. According to Lazar, it would take considerable force to make it move.

Well, considerable force, or considerable precipitation. Shortly after that, we got the latter.

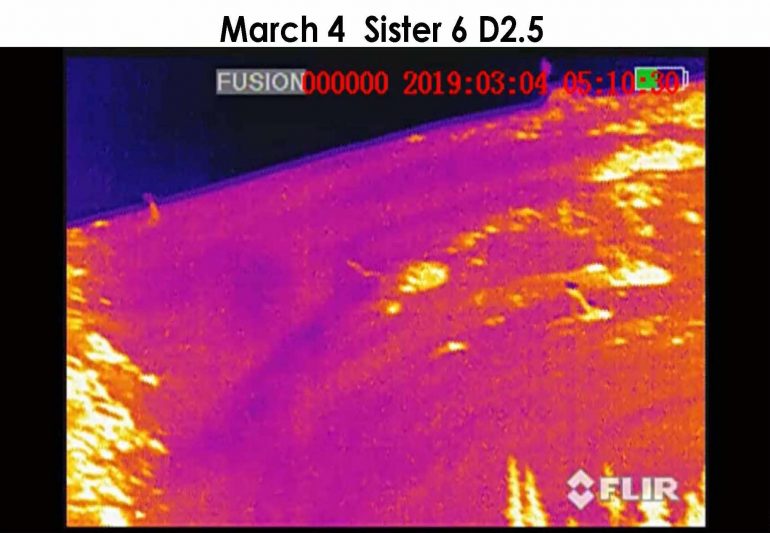

A note on avalanche ratings. For the purposes of Lazar’s talk, he only spoke on the D scale, and did not include R ratings. The avalanche details that follow are all ranked according to potential for destruction as follows: a D1 is relatively harmless, a D2-3 can knock over and bury a person, and a D3-4 can bury a car. D5 is the most destructive possible, with the power to gouge forests, reshape mountainsides and basically render unrecognizable anything in its path.

The first cycle began on February 28. Over the days that followed, snow kept falling and avalanches were drier and largely concentrated in areas of thinner snowpack around Loveland Pass. They were relatively small at D2-2.5, not hefty enough to move a car but enough to bury a person.

By March 3 things were getting rowdy. The snow was coming in wetter and CAIC issued major avalanche warnings in 6 of the 10 zones in Colorado. A car collided with avalanche debris on Red Mountain Pass. Slides began to funnel across 10 Mile Canyon, closing I70 (sidenote: it costs the state approximately $1 million per hour to close the interstate). A backcountry skier was killed in a slide off of Lizard Head Pass. The first D4s were reported on Gothic Mountain and Whetstone. At the height of the storm, the Gothic area had received 3.4 inches of SWE.

According to billy barr Gothic’s venerable citizen scientist who has been collecting data on snowfall in Gothic for decades,“This avalanche path has run this far maybe 2-3 other times in the past 47 years and it just reached the road well past the East River and hit a cabin in Gothic.” Coincidentally, the last time it had ran was the same day, March 3, 40 years ago.

Farther south, Red Mountain Pass became a verified firing range with D3 and 4 slides continually breaking loose. CDOT closed Highway 550 at 9 p.m. on March 3. Due to avalanche danger and debris, it didn’t open again for 18 days.

Thermal image view of an avalanche breaking at night. CAIC uses thermal imagery to track avalanche activity, particularly close to road ways. Image: CAIC

Just as things were heating up, Colorado did get a small break in the storm pattern. But it didn’t last long and by March 7, the Breckenridge area was pushing 100 inches out of the storm and four regional zones were flashing black for extreme danger. By March 8, Lazar was making calls to avalanche experts asking, “remember all those avalanches everyone said would unlikely run again? I want a list of all of them.”

A Power Point slide from Lazar’s talk. Each day of the storm cycle resulted in similar magnitudes of destruction and road closures. The photo of the crown on the left gives good scale for just how big these avalanches were breaking.

On March 9, perhaps the largest avalanche ever seen in the U.S. unleashed in Condundrum Valley near Aspen. Running a mile long and 3000 vertical feet, it cross the valley floor and traveled partway up the opposite side. A house in its path was spared with minimal damage thanks to a wedge-shaped retaining wall.

A new avalanche path formed on Greg Mace Peak near Aspen and it was thought a new one was carved on Peak 1 near Breckenridge (historical photos later revealed it to be a slide path in the late 1800s). By March 10, 4-6 feet of snow had fallen in many areas, which equates to 4-6 inches of SWE. Schofield Pass near Marble received upwards of 12 inches of SWE. The Marble zone had received the brunt of the storms, and a few days earlier, the CAIC had closed popular backcountry ski access quarry road “to protect people from themselves.”

The snow just kept falling. March 11-14 marked the days when according to Lazar, “the San Juans completely fell apart.” A State of Emergency was declared for the region as D4 slides rumbled across the mountains. In Lake City, an avalanche swallowed the sheriff’s home while he and his daughters were sleeping. One daughter was buried. Miraculously, they all survived.

At this point, Lazar was thinking “I would love to go one day without a landscape altering event.”

On March 14, the last known D5 ran off Garret’s Peak near Snowmass, pictured at the top of this article.

And then, as quickly as the mountains had turned into a violent shuddering earthquake zone, the snowpack stabilized, seeming to have purged itself of every ounce of volatile energy. Within a few days, forecasts returned to moderate danger. Tons of debris filled valleys and mountainsides — snow piles, entire forests that had been plowed over, tree trunks snapped like matchsticks.

In the end, 87 slides rated D4 or bigger were reported to the CAIC and over 1000 slides total. Lazar posits that number as a gross underestimate. This summer, CAIC crews employed satellite to investigate widespread forest damage and found 4782 sites that looked as though significant timber had been destroyed. They will continue to use information gathered before, during and after the event to gain a better understanding of avalanche behavior.

So what caused this? Basal weak layers, a strong snowpack and enormous amounts of precipitation. Climate change could also be causing wetter, bigger storms to hit the Rockies more frequently. The whole event illuminated what avalanche forecasters and researchers know about avalanches, but more of what they don’t.

“Cycles like this allow for enormous insight into avalanche dynamics, trends, runouts, impact pressure and force,” said Lazar. “Ultimately we’re still learning.”

Here’s to hoping this coming season brings just as healthy a dose of snow, without the catastrophic slides.

Editor’s note: As backcountry travelers and citizens of mountain communities, we are all impacted by avalanche events. Thanks to organizations such as the CAIC, Utah Avalanche Center, Northwest Avalanche Center, the Bridger-Teton Avalanche Center and more, we can not only travel more safely in the backcountry but also be protected when public roadways are at risk. This season, consider how you can support your local avalanche organizations. Many (including the CAIC by way of Friends of CAIC) hold fundraisers to help fund the research and outreach that keep us all safe in the mountains. For information on upcoming events, check out your local forecaster’s website and post links for events in the comments.

Manasseh Franklin is a writer, editor and big fan of walking uphill. She has an MFA in creative nonfiction and environment and natural resources from the University of Wyoming and especially enjoys writing about glaciers. Find her other work in Alpinist, Adventure Journal, Rock and Ice, Aspen Sojourner, AFAR, Trail Runner and Western Confluence.