A ski-tourer’s take on a retelling of the Dyatlov Pass Incident

I know, I know. You’re not supposed to buy a book for its cover. But the shadowy photo of a group of skiers heading into darkness leapt out like an encoded signal aimed at ski touring aficionados wandering the bookstore in search of a mid-summer read. Dead Mountain : The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (Chronicle Books, 2013) centers around the unsolved mystery of the death of a group of Russian skiers in the Ural mountains on a midwinter expedition.

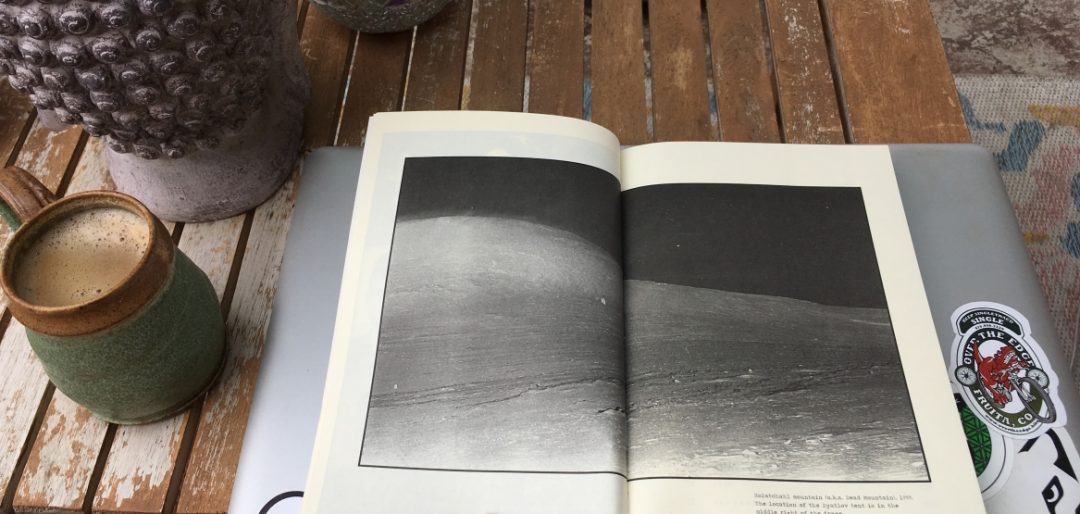

Opening the book reveals a double page spread photo of their objective: Dead Mountain–stark, foreboding and barren. The austerity of the black and white rendering conveys an environment as inhospitable to humans as the bottom of the ocean, or the surface of the moon. The group of students were on a mission to earn their Level III hiking certificate, for which they needed to complete at minimum: a trip of at least 300 kilometers (186 miles) over 16 days with a third of the miles navigating difficult terrain, eight of the days in uninhabited regions, and six of the nights in a tent. All were experienced in outdoor travel, yet none returned.

Juxtaposed against coffee on the patio on a summer morning, Dead Mountain looks like a particularly inhospitable place to be in the midst of winter. The symmetrical profile of the landscape, unremarkable by standard hazard assessment of backcountry travel, plays a prominent role in the author’s hypothesis.

Disturbing evidence uncovered by the search parties fueled the mystery. The bodies of the skiers were found several hundred meters from their tent, which had been slashed open. Nearly all of them were lacking shoes, or clothing suitable to being outside in the dead of Russian winter. One of the bodies was missing a tongue, and several others had shredded clothing and evidence of blunt trauma.

Many of the standard conspiracy theories have been invoked in explaining this tragic accident: secret weapons programs, the always-popular yeti theory, aliens, vengeful tribal locals.

Editor’s Note: According an article published February 14, 2019 in the Moscow Times, Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office is reopening the case which is still considered unsolved. The goal of the renewed investigation is to determine whether a “hurricane, snowslab or avalanche” are responsible for the deaths. Not sure how they’ll determine that 60 years later, but it might be worth staying tuned for.

Part of me read the book for idle entertainment in the murder mystery/documentary format, the other part was sleuthing for vintage Russian ski touring beta. In the former, the author’s experience in creating documentaries showed through with a well paced storyline and carefully controlled build-up to the conclusion. In the latter, it was less fruitful than reading ZMM as a motorcycle-obsessed teenager expecting pragmatic tips on motorcycle repair. I was hoping for more gear detail about skis and bindings, kickwax versus skins, transition stages, and camp setup. The author’s focus was more on researching the lives of those involved in the incident, and formulating a hypothesis for their untimely demise. This book was the author’s initial foray into writing about winter travel, which explains the lack of the gear nerdiness the seasoned WildSnow reader might hope for. The result? Gaps in technical detail, but interesting insights from an outsider looking in.

The most prominent of these insights annoyed me until I had a somewhat humbling moment of reflection. Despite the cover photo, and many others of the group on skis, the author always refers to them as “hikers.” My inner ski touring nerd was irked by this–I bought the book because there are skiers on the cover! Where’s the skiing action? Ruminating on this short shrift in expectations, I realized that from the author’s perspective as a non-skier, the majority of ski touring is composed of an activity that bears closer resemblance to hiking than skiing. Reference Rule 0 of Ski Touring, “Ski Touring is all about walking uphill.” The brevity of time we actually spend arcing turns in comparison to the amount of time spent hiking is is an intrinsic tradeoff that happens so early on in the ski touring addiction cycle, most of us have forgotten it occurred.

The cover photos is one of the last images of the skiers taken before the fatal incident. PC: Amazon.com

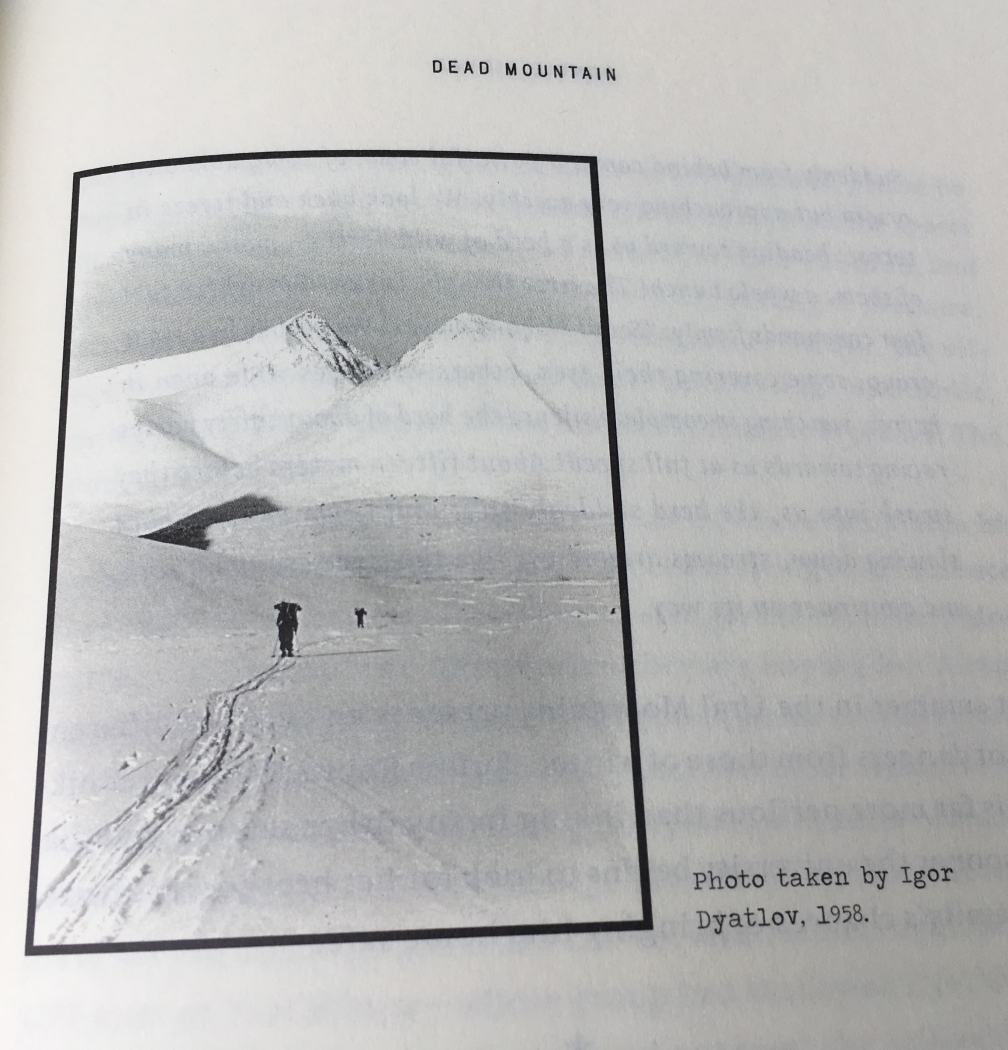

An alternate insight into the “touring” element of “ski touring” appears on early on: “Igor is a tourist–though not in the Western sense of the word. A tourist in the Russian sense is much closer to adventurer: a hiker or skier who journeys into the wilderness to explore new territory and push past personal limits of endurance.” The photo on the following page is a classic image to invoke ski touring wanderlust: a landscape of snow with parallel peaks rising in the background.

Igor Dyatlov, leader of the group, certainly knew something about picking out a compelling ski touring objective. Show me this pic, ask me if I want to go , and I’d be waxing skis before the conversation was over. How many of these enticing peaks inhabit the Ural Mountains?

The strongest element of the book is the rapport the author builds between the reader and missing group of hikers. Tracing the lives of the young adventurers and their varying paths to Ural Polytechnic sets a background of bright, glowing youth and vitality during “the Thaw.” At the time, Russia was beginning to emerge from the effects of Stalinism into a brief period of relatively liberal times.

One of the most unexpected and intriguing insights was into the brief window of freedom and progression during the Thaw that precipitated the group’s cohesion and sense of adventure. “In the mid-to-late ’50’s, for the first time in decades, young Russians felt a renewed sense of promise–sports, the arts, technology and accessible education were all part of this new optimism. It was a hopeful period that wouldn’t recur in Russian history until the fall of the Soviet Union some three decades later. By Soviet standards, the Thaw was an exhilarating time to be young, physically fit, and intellectually curious. The nine members of the Dyatlov group were of these.” The ill-fated demise of the Dyatlov group mirrors the short-lived sense of promise of The Thaw; an undercurrent of wistful regret for what could have been.

Investigators on the scene found little evidence for what caused the skiers to violently exit their camp. Many conspiracy theories were born from the mystery, including the infrasound panic theory. PC: Public domain

My nostalgia grew in the description of route research before the dawn of the Information Age: maps, checklists, and journals evoke the timeless, unplugged draw of the backcountry. Of particular note is the group’s shared journals, which preface the interplay of social media, minus clickbait self-consciousness.

While I was a bit disappointed that nuclear-mutated yetis were not part of the author’s conclusion, the explanation he posits is all the more chilling for how relatively mundane it is, and relevant to backcountry travel. We are accustomed to carefully evaluating decision- making protocols while in transit, assessing slope angles, snow pack, and other hazards, but little press centers around camp life. I will leave the reader to assess the conclusion of the crux of the mystery–what would incite nine experienced backcountry travelers to leave the safety of their tent, woefully unprepared for the brutal cold of Russian mid-winter?

You’ll have to read on to find out.

Aaron Mattix grew up in Kansas and wrote a report on snowboarding in seventh grade. His first time to attempt snowboarding was in 2012, and soon switched over to skis for backcountry exploration near his home in Rifle, CO. From snow covered alleys to steeps and low angle meadows, he loves it all. In the summer, he owns and operates Gumption Trail Works, building mountain bike singletrack and the occasional sweet jump.