While I’m more likely to spend time with a pop musician’s retrospective writing (Keith, and for a time Bruce have had me thralled), I eventually grab just about every full-on adventure memoir that comes out — especially those of the mountaineering persuasion. When I found out my good friend and respected former publisher of “Climbing Magazine” Michael Kennedy had been instrumental in the production of pioneer alpinist Allen Steck’s effort at autobiography, I got a copy as soon as possible and allowed my recliner its due. Disappointed I was not…

A guy drove to 1950s Yosemite in a Model T Ford, and then put up a big wall route that’s still considered a test. Might the story hold your interest? Allen Steck may not be a kitchen table name for many of you reading WildSnow, but if you’re a rock climber or alpinist of any sort, he’s one of the guys upon whos shoulders you stand.

Prepare to be amazed.

Some of you with a background in rock climbing, especially if you’ve climbed in Yosemite, might recall that Steck and his climbing partner John Salathe’ put up their eponymous route on Sentinal Spire long before modern rock climbing as we know it was anything more than aluminum ore still in the ground.

The famed Steck Salathe was done in 1950 (and indeed the climbers drove a Model T). The climb involves a difficult “squeeze” chimney that some climbers get so deep inside they might as well be caving. Steve Kentz and I did the route in 1972, already more than two decades later than the first. Neither of us were even born when Steck and Salathe’ tackled the wall. Steve and I figured we were well prepared with much improved gear and our squeeze chimney technique at least pre-visualized, if not practiced in smaller, safer situations. Piece of cake…

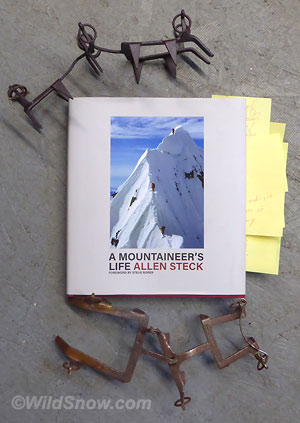

I still remember wriggling up that storied cleft. At times the stove flue crack was not much wider than my head, knees and feet scraping away like a rat scrabbling from an owl, thinking “how the heck does anybody get up this thing!?” Steck’s account in his recently published memoir, A Mountaineer’s Life, underplays the climbing and talks more about their thirst as the crux. So be it, those guys were studs and even horses need water.

The book is a memoir, structured as a series of “me and joe” stories. The majority of the writing is basic blow-by-blow that’s compelling but not particularly deep when it comes to introspection or interpersonal relationships. While such style works for telling “big” stories, I was glad to see Steck’s Childhood, Family and Busines chapters comprising the middling pages. Though with those chapters following a Pakistan climbing epic and leading to a near fatal avalanche, they’re a bit of a non sequitur.

As I’m one of so many (everyone?) who has experienced how past relationships and marriage influenced the arc of my life as an alpinist, I’m always interested in other people’s stories in that regard. Especially when placed in context (or conflict) with the calling (nice word for addiction) of the mountains. You won’t find much of that here. I did get a chuckle when Steck shares regarding a business education his parents encouraged: “I did not want to enter that world,” he writes, but he nonetheless would later be a principle in the founding and early publication of “Ascent,” a beautiful artsy climbing magazine that became a trend setter of the time and apparently remains an annual publication. I suppose Steck differentiated between the corporate business world and that of the non-profit Sierra Club printing a magazine. Fair enough. I like these sorts of goods in a memoir; for most of us life is not binary, the blender often swirls many ingredients.

Ok, back to you climbers out there. Recall that Steck along with Steve Roper co-authored Fifty Classic Climbs of North America, a wonderful dream book that became for better or worse something of a tick list (though the book is often called “Fifty Crowded Climbs”). Oddly enough, while Steck and Roper did have a set of criteria for what makes a “classic,” their selection process was apparently weighed heavily to what a climb looked like, rather than its popularity or potential for enjoyment.

In their re-defining what a classic was, Steck and Roper included one climb in Fifty Classics that to this day remains without a repeat by its original route: Hummingbird Ridge on Mount Logan. (Indeed, wags should be calling the book “Forty Nine Crowded Climbs” or something like that.) Steck was on the team that did the first ascent of Hummingbird in 1965. Again a fairly prosaic blow-by-blow in terms of writing style, Steck’s memoir description of Hummingbird will nonetheless have you on the edge of your seat. If you are at all interested in the extremes of human endeavor, A Mountaineer’s Life is worth this chapter alone.

A couple other chapters stood out for me:

I enjoyed Steck’s story so innocently titled Climbing in the Alps with Karl Lugmayer. This is somewhat of the traditional coming-of-age climbing tale, covering Steck and his friend as they pump around Europe on bicycles, climbing in the Kaiserberg near Kitzbuhel and getting it on with big mean walls in the Dolomite. I was delighted to see the pair had used the Stripsenjochhaus on the north side of the Kaiser — Lisa and I had stopped in there during one of our springtime Austrian hikes. Beautiful place, fun to get a bit of historical context.

The 253 page book is replete with numerous full plate photos, some of which are amusing, some disgusting, some historical, and some simply scary. A few of the images are a bit “off,” which I suspect is because they were restored as well as possible from funky originals, final result limited by the quality of source material. But the opposite could have happened. You never know till you see the originals. As it is, everything is legible and understandable in terms of production values, sometimes stunning.

No adventure mountaineering memoir is replete without an avalanche or two. In 1955 Steck and friends were enjoying an innocent “Ski Weekend at Echo Lake” when they got slid. From what I infer they had two or three full burials, yet everyone survived due to another party happening on the scene and helping out. Not really much here but another blow-by-blow, though Steck ends the piece with a mention of his pregnant wife and the child who “came close to never meeting her father.” More important words were never written.

The book ends with a few pages of “Reflections” that attempt to tie it all together. Steck somewhat succeeds here in relating the final level of his hero’s journey, though I would have rather seen more reflective content larded throughout the book rather than summarized. To be fair, it’s not easy writing deeply introspective prose, one can come off as a self important buffoon, or worse. Perhaps I should shut up and try it more myself before being a stickler. In the end, Steck’s style works, that is what matters.

In conclusion: While this effort by Patagonia’s publishing arm is clearly a climbing book first, it’s also an adventure memoir that will appeal to anyone with a cursory understanding of climbing gear and technique. Steck is most certainly one of the reasons the climbing world is as we know it. He writes in his closing: “I sit now in my rocking chair in my ninety-first year…I have tested myself…and become a stronger person.” Always nice when those so tested share tales of the journey. Enjoy.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.