Drew Tabke

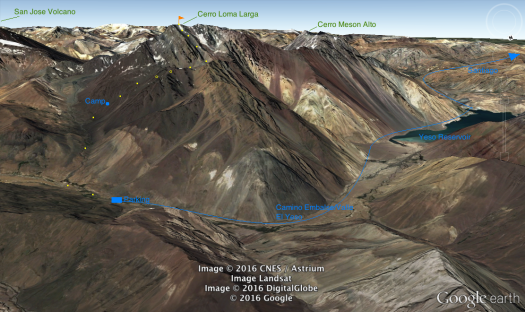

On September 10, 2016, Griffin Post and I skied from the summit of Cerro Loma Larga (17,730’) in the Andes Mountains outside of Santiago, Chile. On day one we made an approach from the Rio Yeso Valley to high camp, and on the second day we made the push to the summit via a broad gully on the peak’s north face, before skiing 8,500 vertical feet back to the truck. We are unaware of other ski descents of this summit or route.

The line we climbed and skied was the result of many skiing adventures in Chile over the last ten-plus years. I typically base myself in Farellones, a ski town above Santiago, where one can access El Colorado, La Parva and Valle Nevado ski areas. From various high points above these resorts, an epic view opens up to the south-southeast towards some of the big peaks of the Central Andes, including the north side of the Cajon de Maipo peaks (see this report from Louie).

Loma Larga in particular stands out, with an enormous couloir dropping from between two of the mountain’s distinct high points. After years of obsessing over this distant view, and an unreasonable amount of time researching the peak on maps, a rough plan was in place to attempt to ski this grand mountain feature with my good friend Griffin.

Griff and I met up in Farellones the first week of September and immediately went on a brief-but-intense trip with our Chilean friends, Chopo Diaz, Xabier Azcarate and Sebastian Goñi. A helicopter picked us up in Farellones and dropped us a short, 15-minute flight from town, below the Cerro Altar — Cerro Paloma group of peaks. In the next three days we climbed and skied two lines from around 16,000’. The heli bumped us back out, and with the weather looking good and Griffin and I feeling acclimated to go higher, we immediately prepared to launch our mission towards Cerro Loma Larga.

Our good friend, Soledad Diaz, had just stepped off the airplane from a four-month trip abroad, where she was skiing in Norway and trekking in Nepal. Though she was jetlagged and hadn’t skied for months, she couldn’t resist joining us for the attempt. The three of us packed up a borrowed pickup truck, drove through Santiago for supplies, and headed back into the mountains.

Our initial approach to the peak was a major question mark. Plan A was a circuitous, snowmobile-assisted approach from the Cajon de Maipo side of the mountain. But this was now off the table as rapid recent snowmelt had closed that access point.

In our early planning, we didn’t expect to be able to drive anywhere near the peak during our proposed dates, but a few very warm weeks in August and early September had cleared many mountain roads of snow, including the road around the Yeso Reservoir, a route that gives direct access to Loma Larga’s north side.

Happy to make it past the Yeso Reservoir, we bed down for the night with beautiful views all around.

Though we hadn’t been able to confirm that the road past the lake was passable, we decided to take a chance and headed that way. Despite a few white-knuckle sections of rutted, side-angled snow banks above deep blue water, we drove the truck around the lake without incident, and rallied another several miles up the Yeso Valley to within a reasonable foot approach of our objective. We bedded down at the roadside for the night.

The approach day was marvelous. We simply couldn’t believe our luck with timing. A week earlier and we wouldn’t have been able to drive within 15km of our starting point. A week later and we would have lost a substantial amount of snow cover for climbing and skiing. We walked in hiking boots for a mile or two into the initial drainage to access the peak where we made a clean transition to skinning.

Freezing levels were forecasted to go to well above 13,000’ during our two-day window, but a high cloud layer temporarily kept us mercifully sheltered from the scorching Andean sun. The route led us along the foot of the mountain’s NE side. After a few hours we located the access valley in the wall to our right that we’d climb up to eventually (hopefully) arrive at the grand North Couloir, the sight of which had inspired the trip. We climbed the initial few hundred feet into the valley to a sheltered bench and pitched camp.

Anyone who has traveled or skied in Chile knows that the sunsets in that country are some of the best in the world. The Andes ramp up from the Pacific Ocean, forming an enormous west-facing slope that runs north to south for thousands of miles. Though our camp fell quickly into shadow, we had an un-obscured view of Cerro Marmolejo (20,039’), the southernmost 20,000’ peak in the world. The light the setting sun cast against its stupendous west wall was incredible, leaving us speechless with its beauty. Once the display was over, and with the alarm set for 2:30 am, we went to bed, wondering what the unknown route ahead would hold.

Mining is Chile’s main industry, and the rich minerals of the Andes make their presence seen everywhere.

Sole preps her pack for the next day while the last rays of sun illuminate Cerro Marmolejo’s west wall.

We roused ourselves as planned and were moving by 3:15 am. It was a dark, moonless night as we departed camp, but we made fast progress. The snow, though hard-frozen, had just enough texture to allow us to skin continuously past sections we expected would require boot crampons. It was cold and we rarely stopped in the next few hours as we climbed higher towards the starry sky.

We’d planned an early departure because we expected to be slowed by a few transitions between skinning and booting, occasional nighttime route finding up our unfamiliar route, and the increasing altitude. We hoped to arrive at the bottom of the big North Couloir by first light.

Instead, with our rapid progress, when we arrived to the bottom of our intended line, it was still pure, black night. Not wanting to commit to the next section of climbing until we could see the snow and terrain to better assess what was in store, we dug in. We built a small shelter of a snow wall against a cliff, melted water, did jumping jacks and walked around the little plateau to stay warm, staring at the eastern horizon for first light to finally break the hold of the night.

Finally, like someone flipping a switch, a faint pastel azure spread across the horizon. From the great height of our vantage point the light grew quickly, and soon we could make out the snow texture in the couloir ahead. It looked like uniform spring snow for skiing on the right, with runnels and pockmarks good for climbing on the left.

After waiting out the last dark hours of the night, first light finally illuminates the eastern horizon.

However, we were confused by the incredible foreshortening. From the maps and photos, we expected to see a distinct, 3,000-foot-couloir. Instead, due to the subtle convex form of the entire north side of the mountain, we could only see upwards about 1,000’, and it was so wide it didn’t even look like a couloir! Beyond the rollover, the rest of the line remained a mystery. So with a small stash of gear left at our mini shelter and crampons on our feet, we set off.

We climbed up and though the conditions were great, each step became a bit more tiresome with the altitude. After about an hour Sole became exhausted. She wasn’t complaining of any altitude-related symptoms, she was simply too sleepy to continue after travelling home from Nepal. She installed herself in a sheltered area to wait for the lower slopes to soften, and wished Griffin and I well.

Griff and I plodded on. We had climbed to nearly 18,000’ together in Chile once years ago, on Cerro El Plomo, but were not nearly as acclimated that time and paid the price with symptoms of AMS. This time we were feeling good and after a few hours, the rolling, blind terrain finally ceded to a view of the summit ridge. We debated calling it good from the col between the two peaks, but with the snow in seemingly ideal condition, and ample time remaining, we decided to climb higher.

While the climbing wasn’t technical, the exposure and great height created a wild feel, and soon we were standing together on Cerro Loma Larga’s central summit. All around us lay the high peaks of the region, Chilean and Argentinean, with the dominant hulk of Aconcagua far to the north. The peaks above Farellones from where I’d first seen the line we now stood on top of were visible as well, appearing to be nearly indistinguishable: tiny bumps and ridges from our privileged perch. We prepared our equipment and clicked into our skis.

Griffin’s first legitimate ski descent on Dynafits, and he choose some steeps at 17,700′ for the test run.

Skiing off the summit we found wind-compacted powder, unexpectedly superb snow for such height. We linked turns down the very steep, rolling slope. Each turn we trended slightly left, keeping us on the steeps instead of returning to the middle of the gully below.

The terrain was like nothing I’ve experienced before — it was as though the summit structure itself, and then the entire skier’s left side of the grand couloir below, was all a single enormous wind drift. It was like an endless left-hand wave, or a 3,000-foot-long quarter pipe, that gradually rolled over along its downhill fall line, making the slope both convex and concave simultaneously. The snow slowly transitioned from consolidated powder into good spring snow, and we continued along this grandiose slope all the way to the bottom.

Arriving to the lower section of the couloir, Griffin finds another interesting snow feature to shralp.

We cheerfully regrouped with Sole who was hanging out at the shelter we’d built in the pre-dawn hours. Looking back up to the line was anti-climactic, as the nature of the incredible run we’d just experienced was again hidden behind tricks of scale, convexity and perspective.

The three of us skied together back down the long valley we’d climbed in the night, finding more superb, rolling spring skiing. We collected camp, and with our cumbersome packs continued skiing out to the valley below, able to link snow patches to within a quarter-mile of the truck, 8,500’ below where we’d tipped in off the summit a couple hours before. We reached the truck, pulled off the boots with a sigh of relief, and headed back down towards Santiago with visions of returning to this incredible group of mountains already taking shape in our minds.

(WildSnow guest blogger Drew Tabke, 32, was born, raised, and made a skier in Utah. He now lives in Seattle, skiing at Crystal Mountain and in the greater Cascade Range. He is a competitor on the Freeride World Tour, ski guides independently in Chile, and guides with H20 in Valdez, Alaska. His industry partners include Eddie Bauer, Giro, Panda Poles and Praxis Skis. He is most interested in moderate corn skiing during sunset followed by a quality cocktail, though occasionally he enjoys deep powder and steep terrain.)

After picking up camp, Sole continues the long descent, technique still perfect despite the big pack.

Being the month of Chilean Independence Day, the boys brought a chupaya, a traditional chilean cowboy hat, to the top.

Coordinates of the central summit of Cerro Loma Larga: 33°41’14.6″S 69°59’17.7″W

Coordinates of the central summit of Cerro Loma Larga: 33°41’14.6″S 69°59’17.7″W

Beyond our regular guest bloggers who have their own profiles, some of our one-timers end up being categorized under this generic profile. Once they do a few posts, we build a category. In any case, we sure appreciate ALL the WildSnow guest bloggers!