Spiterstulen hut and lodge complex. Not only are the Jotunheimen mountains large, but they rise from high and broad valleys that give an odd visual effect that’s not unlike the cover of a Viking fantasy novel. The vertical relief appears improbable, and due to the valley widths you see quite a few different peaks with only a small amount of movement, unlike narrower closed-in alpine valleys I’m familiar with in the Alps and Rockies.

I know a few of you readers make it a habit to ski tour the Norge, but for most (especially North Americans) Norway is an expensive, remote place with mysterious customs involving Vikings, trolls and caviar. Moreover, the sun virtually disappears for a few months each winter, (in turn exacerbating the troll problem, while making backcountry skiing exciting albeit cold and perhaps uninviting to all but the hardcores). So most alpine tour skiers trend their home ranges, or travel to better known venues such as the Alps.

Money should be mentioned here. Norway would be difficult to afford for ourselves even with the obscene advertising profits of WildSnow dot com, but through the help of Marker/Volkl as well as various lodges (we’ll write about them all here over coming weeks) and the Norwegian Tourism Board we’ve made it up to the land of fish, fjords and offshore oil — not to mention folks so friendly that even being a grinning American skier feels grumpy.

How to make Norway ski touring affordable on your own dime? A couple of travelers tipped me off. One suggested that finding package deals at least allows you to budget. If you just show up and start stabbing plastic at restaurants and hotels your bank account will suffer — you might even go bankrupt. For example, one of the Norwegian Norge ski touring guiding for backcountry. offers a trip that includes transport and full board lodging for about $230/day USD per person. That’s pretty good. Another budget travel method is to do 100% tent living, while renting a car with a group, or even buying a junker automobile. As for day-to-day food, if you shop carefully in grocery stores you can do okay with prices similar to more expensive towns in the U.S., but don’t even touch the popular gas station snacks or food. I bought a bag of corn chips that cost me fully $8.00. Fuel is expensive ($7 to $8 per gallon USD) and so are the trains, so a truly budget trip will involve minimal changes in location. Above all, the locals are super friendly so network into it if at all possible.

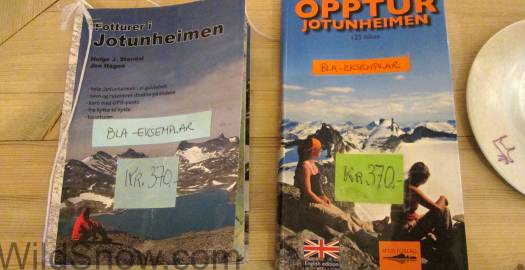

Guidebooks for sale at Spiterstulen. The house library at these lodges is extensive and includes all the guidebooks, so if you’re on a budget you can just study and shoot some smartphone shots. If you want a book of your own 370 krone is about $50 USD. Ouch.

For me, the Norwegian mountains have always been a land of mystery. Vague pictures stuck in my head: a few images of fjords and telemarkers for the most part, probably picked up from old ski magazines. Also, I’d for years had the impression that most backcountry skiing Norwegians scooted around large, low angled expanses of treeless snow, towing children in traditional wooden sleds along with enormous bundles of sauna fuel, head to toe dressed in hand woven reindeer fur sweaters, of course.

You think Norway is all reindeer and wool sweaters? Sometimes it is, but the ski touring crowd here is probably the most modern equipped I’ve seen anywhere in the world. It’s a prosperous country these days and the gear scene shows it.

My imagination was not far off the mark. According to our guide and trip organizer Stian Hagen (he’s been skiing here since he was a toddler following his skier parents around), until several short years ago you’d see 90% nordic type ski touring gear (lighter weight tele gear or even full nordic) at even the huts with the best alpine ski touring access.

Now, at huts with access to mountain terrain you see more than 90% alpine touring gear, nearly all being tech binding equipped, with a few frame binding and telemark holdouts if you look closely.

That’s a huge change, a shift in culture that I would not have believed unless I’d seen it with my own eyes.

Spiterstulen will pack your tour lunch. Check out this variety of translated menus. You check off the list, fill out your name, leave your thermos. Nice to see a good system like this that gets all the mountain folk out the door and enjoying themselves.

A younger “modern” group of backcountry skiers has been the force for change, the most influential probably being “Norway’s best known freeride pro skier” Stian Hagen. From a lifetime of Norwegian mountain recreation (he began as a toddler, with his parents), Stian knew Norway has lots of mountains, tons of snow, and a long “spring” ski touring season that’s perfect for summit descents and high tours.

The “biggest” of the Norwegian mountains in terms of summit elevation are those in the Jotunheimen range in southern Norway. Here about a three hour drive northwest of Oslo you find the highest and second highest peaks in Norway, as well as an extensive system of huts and lodges. Some facilities date back more than a hundred years. More, due to this being a peak studded high elevation plateau the “base” terrain of the Jotunheimen is mostly above timberline, thus avoiding dense timber at lower elevations that can be unpleasant for skiing.

For all I know this portrait of a mountain man at Spiterstulen is one of Stian’s relatives. Seems like most of the people you talk to are related to the person you ask them about.

For the past few years, Stian (with the help of local lodge operators and other skiers) has been promoting a “high route” thorough the Jotunheimen. The idea is to match the experience of the many routes in the Alps that connect comfortable huts and lodges with ski tours through alpine terrain.

This year our “Stian’s Jotunheimen Haute Route sampler” is a group of six. Photographer is Scott Rinckenberger, freeride touring photo subjects are pro skier and oceanographer Adam U, Swedish ski magazine editor Tobias Liljeroth, Arcteryx clothing designer Greg Grenzke, and the lone guy on tongueless boots and 1-kilo skis, me.

The ideal Jotunheimen high route begins at the eastern side of the range and moves west. If done in its entirety, the Haute Route climbs 6,708 meters and slogs it out over 77 kilometers. Five days is the never-stop standard, though I think most groups would benefit from a rest day or two.

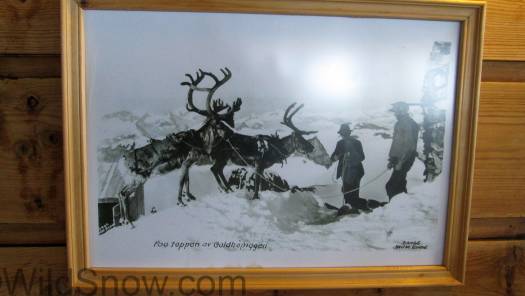

This year the eastern sections lack snow, so instead we moved the start westerly to Spiterstulen Lodge (see map below), a large mountain lodge complex that’s been receiving guests since 1836 through six generations that from the photos hanging in the lodge resemble a multi-generational dude ranching family of the American west. Only in this case the livestock are reindeer, the lodge has a swimming pool, and the cowboys sport ice axes.

Driving from Oslo to the Jotunheimen is beautifully classic, everything you’ve imagined Norway to be. Exiting Oslo there’s not a mountain in sight, but you can feel the road gradually gaining altitude as you motor the Sojoa River valley (famous for rafting). The hillsides are replete with green hay and farm houses you could drop into any alpine country.

Unlike western Europe, the driving here is peaceful to a fault. I’m told the speeding laws are so strictly enforced it’s rare to see any frantic driving. Word is if you’re a certain percentage above the posted speed, you pay 10% of your yearly income as a fine. They might not have the death penalty here, but that could be a fate worse.

Alpine feelings begin near the village of Ota, where white peaks loom above conifer blanketed hillsides. These are the trees that Jotunheimen ski touring seeks to avoid by being mostly above timberline. I’m told once you get down into these forests, despite there being snow they quite dense and unpleasant.

Norwegians are prosperous and have posh mountain lodges all over the place, but thousands just snow camp. They’re crazy but in a good way.

Reaching Spiterstulen involves a long drive up a muddy dirt road (rent something appropriate if you visit). You break timberline just below the lodge, while the literal giants of the Yotunheimen loom before you; an alpine region that requests — no, shouts — to be explored by foot or ski.

While not located at a high point as many Alps huts are, Spiterstulen has a definite alpine feel due to timberline being a few hundred meters below. The main lodge has a large lounging area and dining room with plenty of seating at 10-person tables. Breakfast is served buffet style while dinner is brought to the tables by staff. The food was fine, basic healthy fair with Norwegian quirks such as gjetost cheese brown cheese and caviar in a tube. Hot, soft boiled eggs were a crowd favorite, both for breakfast and as sandwich filling (you make your lunch buffet style with ingredients provided at breakfast.) It’s possible to go gluten free, but nearly everything is based on having a bread foundation so only skip the wheat if you really must.

One thing about Norwegians, they don’t mess around when it comes to history. Lodges such as Spiterstulen decorate with photos depicting past history of the place whether the subject be farming or skiing. The place began taking guests in 1836 and has continued to do so through six generations of family ownership. The rooms and main lodge have just enough rusticity to not feel too slick yet still feel established. In terms of recommendations for ski touring, if you need a lodge you can drive to Spiterstulen will work fine, though other lodges are available that compete in different ways (blog posts coming).

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.