We have been tent bound for days, and days, staring at the suffocating whiteout outside our little yellow domed world. We’ve ventured out a few times for existential sensory-deprivation tours, but we were all going a little crazy. Friday night the weather cleared, and we stayed up late taking in the moonlight on the mountains we hadn’t seen for nearly two weeks. The next morning we woke early, and the clearing had held; it was beautiful.

We soaked in the sun’s rays. They warmed our bodies and rejuvenated our stoke. However, with unsettled storm snow conditions, we tempered our expectations and set out on a day of cautious skiing. Difficult, as this was probably our only weather-free day for the rest of the trip (if the forecast is to be believed). We headed up to the backside of a north facing slope we had skied earlier in the trip.

Skinning out from camp. After days in a ping-pong ball, the mountains look incredible. It’s as if we were seeing them for the first time.

As we approached the slope, we saw a few tents in the distance on the glacier. Coop and Jason went over to talk with them, while the rest of us headed up the south-facing slope above to dig a pit. The tents belonged to four people from Anchorage who were doing a ski traverse. They had been traveling through the whiteout and now were planning on skiing some of the surrounding peaks for a few days.

Our pit provided mediocre results, so we continued a bit farther and dug another. The pit had several layers from the storm, rapidly warming in the sun. We turned around and skied down the lower slope, with our sights set on a nice, north facing slope in the distance.

After a long walk across the flat Riggs Glacier and a short climb, we arrived at the top of an enticing north facing shot to a small arm of the Riggs below. Still concerned about the new storm snow, we set up two belays, one to cut some cornices on another nearby slope and another to do a belayed ski cut on our intended run.

Unfortunately I can’t read everyone’s comments while out on the glacier, but I was told there were some questions about our belayed ski cut techniques. I’m a huge fan of utilizing belayed ski cuts and snow pits, which Alaska is often quite well suited for.

Often we are able to boot up the south face of a peak, which is usually more stable (especially in the morning), or skin up in some way that we avoid the steep north face we’re intending to ski. This serves the purpose of minimizing avalanche danger on the ascent route, but unfortunately doesn’t allow much useful snow evaluation on the way up. It also goes against the old ski mountaineering adage of climb what you ski (which applies more to lines involving complex route finding or evaluation of firm avalanche-free snow conditions. In the case of possible avalanche conditions, way better to hit first from the top, one skier at a time of course.)

Of course we make a judgment call beforehand whether we think a slope is safe to ski. Even so, at the top of almost every run, we have been setting up an anchor and belaying in for a hefty ski cut and a quick snowpit.

We normally dig a solid dead-man, with a pair of fat skis buried several feet deep, and belay using that as an anchor. Depending on the specific situation, sometimes we clip the anchor into the haul loop of the belayer’s harness (who is dug in himself), or alternatively, belay directly off the anchor. The later method is stronger, but I feel that it puts more force on the anchor, and is more difficult to give a dynamic belay–essential for a ski cut. Also, if the former method fails two people are put at risk, along with several other pros and cons.

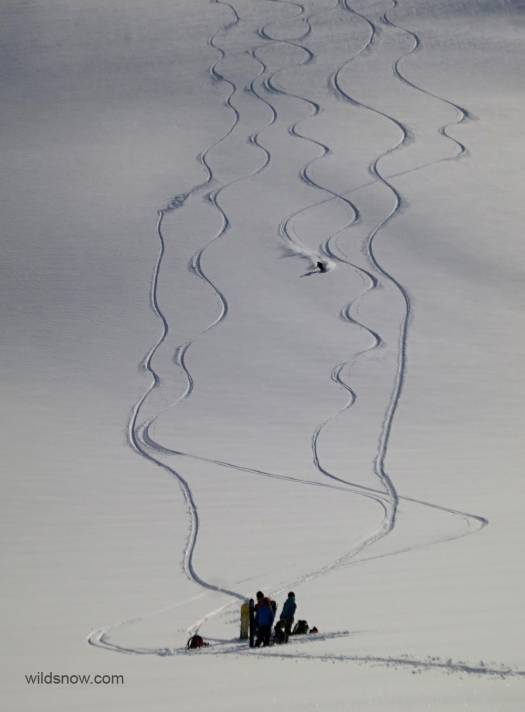

After setting up, we send someone in to do a hard ski cut at the entrance of the line, which is often a convex roll. After a few turns and hops, he’ll dig a quick pit. If the pit looks fairly similar to the other, more extensive pits we’ve dug on the trip, with no red flags, we’ll go for it. The ski-cutter will unclip, and have himself an epic run of steep first tracks.

It’s not a foolproof method, but it can add an extra layer of safety when the group is already confident that a slope is safe to ski. I’ve always felt that un-belayed ski cuts, especially on large, exposed slopes, are risky. If the skier does start a slide, he has a good chance of getting caught in it. I’ve done my fair share of both, and started a few slides with both methods. The margin of safety feels tenuous at best when I’m not tied in.

When you’re already a few turns down a run, at the end of your rope, it’s perhaps the hardest point, mentally, to turn around and say no to skiing that run. That is the major reason why I don’t rely 100% on belayed ski cuts and pits and only use them as a sort of “confirmation” and extra layer of safety on a slope I’m already fairly confident will be safe.

Why ski cut at all? It’s certainly not necessary, but consequences and risks are already high on a ski trip like this, so it is nice to be able to minimize both a tiny bit. Also, the extra time and effort required is often minimal. When the run below is one of the best of your life, it’s worth it to spend the extra few minutes for a bit more peace of mind.

I skied into the run on belay for a quick ski cut and pit. Everything looked good, so I untied, and linked nice powder turns to the bottom of the 2,000 foot pitch. After days spent tent-bound, it felt incredible. Moderately angled, beautiful powder, under clear sunlit skies.

At the bottom we regrouped, and discussed our options for the rest of the day. Still wary of the new storm snow, we decided to stay off any steep northerly slopes, and head for some west facing, sunlit slopes above camp, that we had dubbed the “camp wall.” The slope was a few hours away, so it would be somewhat solidified from the evening cooling. We slowly made our way up an icefall on the back side of Tomahawk, and ended up at the top of our chosen lines. The snow, after baking in the sun all day, wasn’t the best, but the setting sun was beautiful. And, the chance to ski right to our tent door was hard to resist.

We set up another belayed ski cut, which only served to show the hard crust that had formed on the face, and Jason dropped in. I decided to ski last. After everyone had skied, I waited a moment at the top, watching Glacier Bay catch the last of the sun’s setting rays. In the distance I could see the ocean feeling it’s way among the glaciers through steep fjords. Beyond that, I could see enormous, mysterious mountains, part of the imposing Fairweather range. From there, glaciers and peaks flowed in like waves, finally breaking on the shores of our tiny campsite, nestled at the top of the Riggs Glacier–sight I won’t forget for a long time. I tipped my skis forward, and sliced through the golden-orange, sunlit snow.

Our camp as seen from the top of the last run of the day on the “camp wall”. You can see our camp as the dot in the lower center of the photo. Most of our skiing has been on the north faces of the peaks in the background.

Louie Dawson earned his Bachelor Degree in Industrial Design from Western Washington University in 2014. When he’s not skiing Mount Baker or somewhere equally as snowy, he’s thinking about new products to make ski mountaineering more fun and safe.