Lisa on Mount Hood.

Successful marriage is often about compromise. In the case of backcountry skiing, my wife Lisa likes small doses of the wild, interspersed with hot showers and central heating. I prefer a snow cave. The key to conjugal bliss: visit a mountain with quality lodging, preferably where we step out our door and into our ski bindings.

One such place is Mount Hood. Rising from the vast forests of Oregon like a white citadel, Hood makes your feet itch for steel edges. Iced by a dozen glaciers and graced with year-around skiable snow, the peak offers numerous ski and snowboard mountaineering routes. You can drop from the summit down several extreme lines, while the lower angled terrain below the summit crags offers turns for every ability level. The lodging is equally splendid.

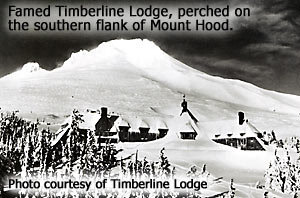

Massive and charismatic Timberline Lodge roosts like a gigantic eagle’s nest at 6,000 feet on Mount Hood’s southern flank. The edifice was built in the 1930s as a government work project during the Great Depression, and endures as a classic example of Northwestern architecture (it is a designated National Historic Landmark). Rustic hand-crafted wood dominates the interior, while vaulted ceilings and stone fireplaces lend a timeless appeal. You get the feeling that a millennium from now, a pipe chewing archaeologist will be brushing dirt from the foundation, exclaiming “by Jove, Timberline Lodge!”

Timberline Lodge.

Timberline’s rooms are cozy, the showers hot. The Cascade Dining Room is renowned for its menu of regional delights, including a desert cart that sags with Cascadian sized treats, trundled to your table by a white coated waiter, ready to serve as many calories as you dare confront. In all, the perfect conjugal ski destination for the Dawson union.

At home in Colorado, we’ve come to expect a worthy spring ski season: a time of sunny days, perfect compacted snow, and good weather. This year we had the blue sky, and nothing else. Winter had been as dry as the Gobi desert. Spring came and the snowpack melted like an ice cube on hot asphalt, instead of compacting and forming the vast fields of perfect-corn snow we expected. After weeks of trudging dirt trails to meager sun-battered snowfields, I was a beaten man. When my angst hit our marriage, I knew a civilized junket was in order; with plentiful snow, handy lounge chairs — and time to enjoy matrimony. So, when Lisa suggested we spend some time together, perhaps with snow involved, my reply was swift, “Timberline Lodge, Mount Hood, the great Northwest. We can climb, ski, and lounge by the pool — something for everyone!”

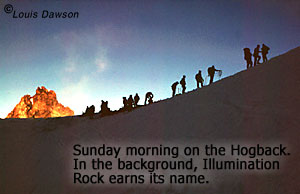

Illumination Rock.

Our first morning. A squawking 3:00 A.M. alarm throws us out of bed. We gnaw stale bagels as the room lights burn our sleep-glued eyes. Our goal is the Hogback Route to the summit of Mount Hood. The easy trade route — perfect for Lisa’s first ski and climb of a glaciated peak. First we pay our admission, in the form of toil. All the south side routes, including the Hogback, begin with a 2,600 vertical foot climb up the Mt. Hood ski area located on Palmer Snowfield. You can buy a snow-cat ride, but we take the slog. We’re not alone.

Scores of people are climbing. Most on foot, some on skis, a few on snowshoes. Many head for the summit. Others hike the ski area slopes. Being used to the solitude of Colorado’s mountains, we get cynical about the crowds. Our haughty vain is short lived. A few hearty halloos tell us that these people are truly enjoying their Hood. Young and old, experienced and novice, local and tourist, it is alpine holiday for everyone. We’re part of it, and we catch the mood; talking with other groups about gear and routes, commenting on the terrific weather and stunning vistas.

Palmer Snowfield.

In an hour we leave the ski area behind. A splendid pink sunrise greets us as the Steel Cliff wakes up with rockfall and wet snow slides. Judging from the constant sludge flow, I wonder why the mountain is still there. The last volcanic eruption was in 1865; another is inevitable.

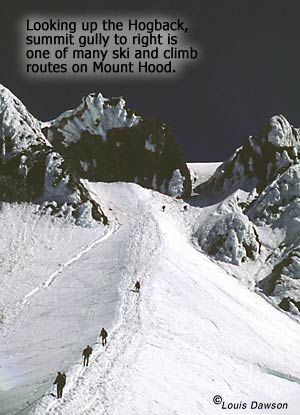

Mount Hood Hogback.

We give the Steel Cliff room to rust in peace, and hike into a volcanic area known as the Devil’s Kitchen. Volcanic gases spew. A smell halfway between crypt and skunk bites our nostrils. Picture an ancient volcano crater partly filled by a glacier. In one area the ice is held back by the heat to expose a steaming pile of technicolor waste. As the lava walls of the cirque crumble they expel a constant dribble onto the dirty snow below. Like smoking ribs hot off a barbecue, ridge crests steam in the sunrise above, broiling from the heat of the earth.

We ski past Devil’s Kitchen, then at 10,500 feet intersect the Hogback, a low angled rib of snow that leads to several short 45 degree gullies. These in turn lead to the summit. Lisa leaves her skis and we crampon to the sunrise. The summit of Hood is sublime. Mount Jefferson rises to the south, with Rainier, Adams and Saint Helens to the north. On a clear day you can see the ocean to the west, while the dense forests of the Northwest blanket the foothills. The summit register is the size of a footlocker. Popular place.

Lisa begins her downclimb, kicking the toe-points of her crampons down the well-worn track in the left Hogback Gully. With trepidation I click into my skis. Several years before I had done a ski descent of this mountain down the less direct Mazama Face just west of the Hogback Route. The Hogback gullies are more direct lines, and during some years they fill with so much snow that the angle decreases. During those times they’re skied often. This year they are steep and seldom skied, while the Mazama Face is being skied several times a week. If you fall on either route, you’ll end up in a yawning volcanic crater where several sets of human remains are said to be. I take the gully.

Hunks of ice studding the Cascade concrete make my first turns turn feel like a schuss down a staircase. Without warning, one of my skis punches through the icy crust into mush beneath, while the other rides the surface. It’s impossible to turn with my skis in the snow. With a lunging jump I pull them up into the air, change direction, then scratch out a bumpy landing.

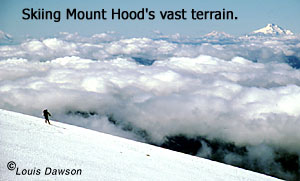

Skiing Mount Hood, Oregon.

The snow is better in the Hogback Gully; denser and smoother. But patches of hard blue ice keep me honest. The steep pitch makes jump turns easier. But at its narrowest the couloir is about two ski lengths wide: tight arcs required.

After about a hundred feet or so the crux opens onto the Hogback. Here the snow is a perfect contrast to the junk in the gully: a thawing dense pack that is superbly skiable. I cut loose. Pumping turn after exuberant turn, I drop to the south side of the Hogback until I’m looking straight down into the gaping bergschrund.

A quick traverse, a few more turns, and I’m with Lisa at the base of the Hogback. This is where most people ski from, and the reason for that is clear. Below us is 4,000 vertical feet of superb, low angled corn snow — a velvet road leading straight to the lodge.

Raptors on the wind, we dance. We swoop down. We try subtleties of balance and leverage on the billiard table corn-snow. Traverse for a variation, ski the side of a rib or drop over a roll, pick up speed, carve a big arc. We stop and the view west astounds us. We’re looking out over a vast forest that crawls to the Pacific Ocean. Small maritime clouds stud a thick blue sky.

Corn snow ski touring on Mount Hood.

We cruise, we laugh — smiles split our faces until they cramp. We glide into the lodge, floating on our grand morning. After a hot shower, as we linger over newspaper and coffee, one thought dominates: This is the best!

The best got better. The weather was too good to brag about — a string of blue days that laughed in the face of typical Northwest rain and clouds. For seven days we climbed and skied perfect corn snow, sunbathed by the pool, and languished in the hot tub.

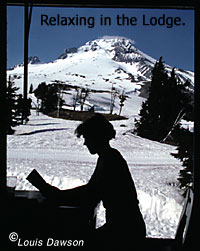

Lisa relaxing in Timberline Lodge, Mount Hood out the window.

Yet being human and married we had our frictions. Lisa was biased towards extreme lounging; I preferred the semi-extreme skiing. But in conjugality you need accord, so we settled on one thing: Between climbs and naps, we would shovel our common ground off the desert cart in the Cascade Dining Room. Our agreement worked — especially since those calories needed burning.

Information about Mount Hood ski mountaineering.

(This article is based on Lou and Lisa Dawson’s wedding honeymoon trip in 1985.)

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.