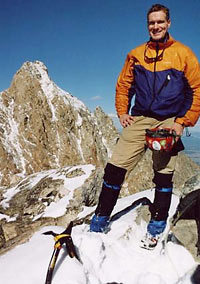

Hamish Gowans

Hamish Gowans, 2004. Self portrait used by permission.

Climbing all 54 Colorado 14,000 foot peaks in winter, attempt at doing them all in one season. (Editor’s note, the first guy to climb all Colorado 14ers in winter was Tom Mereness who completed his quest in 1992, in 2005 Aaron Ralston became the first man to solo climb them all in winter.

April 6 – 2005

Thanks Everyone!

Spring is here and next winter is worlds away. Everyone is gearing up to enjoy the time of year where precipitation isn’t frozen, and we give thanks for the change of seasons that keeps life new and interesting.

Before you all go, however, I would like to praise and thank several people for their involvement, assistance, and support during this winter’s project. Remember this: those who worry about you, advise you and believe in you give you the strength to reach further. I would not have been able to accomplish as much as I did in this challenge without them.

So, thank you to my family and friends. Meaghan for the place, Mona for the floor, Kelly for the tool, Dave for the GPS, mom and dad for the money, and everyone else who tuned in psychically or through the media. I’m glad you were there.

Thank you to the media who were interested in the project and brought attention to our high country that we all need to steward and respect. In particular, I owe a debt of gratitude to Lou Dawson, Jason Blevins and Dave Phillips for their devoted and consistent coverage of the “epic”. To my mentors and exemplars, who inspired and counseled me. To Lou – you started all this! To Tom Mereness, for having been the first. To Jenny – I did this all just to impress you! To Kelly Cordes and Mark Twight, who provided my mantras “this is what you wanted, this is what you get” and “sufferrrr!”. Thank you each and every one.

To my sponsors, who provided durable and well-designed gear, thanks a million: Cliff Bar, La Sportiva, Backcountry Access, Cloudveil, Black Diamond, Mountain Chalet.

Last, but not least, thank you, dear reader, for tuning in and following along. I hope I’ve been able to give you a taste of the experience, and that you’ve enjoyed the ride.

March 15 – 2005

Calling it a Day

After a month of inactivity, it has become difficult to avoid, then necessary to admit, that my project will not reach fruition this year.

For four weeks Colorado was in a pattern of unsettled weather that brought snow showers to the peaks at least every other day. Drinking coffee in Colorado Springs after going for a run, and listening to the CAIC forecast, or looking at weather.com, I kept hoping for a break that would let me return to my mission. It never happened. By the last week of February, even though the weather was starting to improve, I decided to wrap the project because not enough time remained in calendar winter to finish bagging all the peaks.

“Why don’t you just keep going? It’s still winter-ish,” my friends urged me.

As much as I would have liked to keep climbing, I would not have been able to say I had succeeded at what I set out to do. 54:14:1 was an attempt to climb all 54 official fourteeners in one calendar winter and I failed to do that. Changing the nature of the challenge, solely for success’s sake would have been, well, ugly. It would have been like missing a gate on a slalom course and then saying that you were attempting to do the race with one missed gate. It smacks of self-serving vacillation, or worse: cheating. And since I made the rules, I would be cheating against myself. That’s a foul I have to call on myself. The fact remains; I did not achieve what I set out to do.

My own growth during this winter of long meditative hikes alone in a serene landscape has had a fortifying effect on the rest of my life. Contrary to the outward appearance of defeat, I’ve found myself fit and capable, smart and strong, focused and energized. The hills will still be there for a long time to come and I’ll return again and again.

By putting myself in that environment, where the summit clearly, simply, was, or was not, obtained and could only be attained by my own wit and grit, the mountain yielded nothing, forcing me to show my mettle. Wilderness, as land free of the “simplifications” of modernity, can provide us all with clear and honest reckoning when we need to touch our own personal bedrock. Sequester yourself occasionally and look at what is reflected in your accomplishments there.

Dream What May Come

So, I would say that along with his being the first to solo all the fourteeners in calendar winter, Aron Ralston probably has the current Winter Grand Slam speed record, albeit one that can undoubtedly be improved upon (Aron took 7 seasons, while as far as I know, the other two men who’ve done them all in winter took more time than that).

I had imagined that starting a speed record competition amongst climbers might be a result of my 54:14:1 project, and hope that others take up this challenge. I believe the WGS could be done under 30 days with ideal conditions, but just how fast is something we won’t know unless we try to hit it as hard as we can.

Employing drivers, snowmobiles and cooks would undoubtedly aid in an attempt, but we should refrain from using excessive technology and instead make the challenge the athlete’s to overcome. Weather is the great unknown and could keep things interesting as we each try to accomplish what we can with the winter we encounter. Still, unless we use the same equipment, we’ll never be able to completely declare one athlete faster than another because we’ll be talking about the systems they employed as much as their individual fitness. Snowmobiles by and large erase one of the great challenges of winter on the fourteeners: long approaches over snowed-in access roads. Furthermore, claiming a faster time due to more aggressive use of mechanized transport is a slippery slope culminating in someone taking a helo to the highpoint of each and “doing them all” in 48 hours.

I’m hoping to coalesce all my reflections into a slideshow that simultaneously educates about winter climbing, celebrates Colorado high country, and (hopefully) provokes others to try their own projects. Driving down from Pikes, I got a call from Aron Ralston. We talked about the convergences between our two projects and I got to congratulate him on his success. He said that my attempt had helped light a fire under him to finish up, which is an effect of inspiration I intended to have on others through my seeking and striving. Perhaps presenting the thrills I experienced during the project will encourage someone else to give it a shot or maybe fire me up to try it again next year.

March 10 – 2005

Pikes Peak

Jason’s been buggin’ me to do just one more climb – one more so that he can tag along. He’s a reporter from the Denver Post and wants to do a profile on me and the project. It will run next to the news of Aron Ralston’s long-awaited success in doing the winter grand slam (over multiple seasons). Having someone else along on what’s been a high, lonesome sojourn was an energizing proposition too.

We planned to start the climb at zero hour in order to catch the sunrise from Pikes Peak’s summit, which towers over the amber waves of grain to the east. Both of us had been up for 18 hours by the time we headed up from the crags trailhead, but we both buzzed with mojo. Jason’s came in a can: Red Bull at the trailhead and another in the pack. Mine came from the excitement of doing a peak with a companion, but also from doing a peak for fun. Pikes was to provide closure to the project by being the 27th peak and getting my total to exactly half, but also by being the last peak I would do this winter as a part of 54:14:1, the Fourteenerama Gran’ Slamma Winta Jamma.

Jason’s a glutton for punishment, I guess; he went running and then lifting during the day and then came down to climb Pikes at night. I might have climbed faster, being a little better rested, but I was so thrilled to have another person along that I talked and talked and talked. My hyperlocution might have prevented an actual conversation, but it kept me using more oxygen than him and kept us at about the same pace. (I’ve also been very talkative when on my own, but I don’t usually share that in mixed company, of course).

There are also other things happening in my life that I’m excited about, things that I’d put off to attempt the Winta Jamma: finishing my BA, getting an athletics-related job, getting a job, moving off my friends’ couches, etc. Some of us live our lives in binges, overdoing one thing and forsaking others so that a counterbalancing binge is necessary. It keeps things fresh and interesting. I was actually looking forward to bingeing on work and school, ha! These are some of the things I also do, to keep myself from becoming “that fourteener guy” and finishing off the project was also the beginning of the next project. Maybe I’ll call it the School’s Cool Working Fool Hamish Improvement Tool!

Once past treeline above the Crags campground on Pikes, there is a long slog to the next landmark: the Devil’s Playground. This slope is boring in the daytime, but at night it is completely devoid of any waypoints to mark one’s progress so it was great having someone to talk to for the climb! After surmounting an ignominious hump of a summit at 13,040’ (the highest point in Teller County), we followed a path along the ridge above Glen Cove. We wound through a few hogbacks and then reached the Pikes Peak Toll Road. It was here we caught the first glimpse of the summit, or rather the blazing beacon of light left on at the summit house that’s visible from miles around.

Unfortunately though, the donut shop is closed! Lights on but nobody home.

The next section of the ascent is a long hike along the road. It’s mostly clear and sometimes plowed, maybe for maintenance up at the summit, but still long. Jason remarked that the light made it seem just a few hundred yards away for the entire hour and a half that we spent chasing the receding mirage. At some point, the road seemed to end, and we seemed to be at a large built up area with water tanks, railroad tracks, observation decks, and warehouses. Then we found the “Welcome to the Summit of Pikes Peak” sign and rejoiced. On the downwind side of the gift shop there was just the perfect little spot to huddle and brew some hotty choc.

We dozed for an hour until the sky began to lighten, made more hearts-and-toes-warming beverage, and then got ready to take some pictures. When the sunrise actually started to happen, it went from phase to phase so quickly that we raced around, both of us with cameras in hand, shooting each other and all the glorious light we could focus through our lenses. Sadly, no picture is ever going to have the hemispherical view that eyeballs do, nor will it have the chilling wind or the warmth of those first few rays of molten gold.

I’ve reflected since that sunsets and sunrises have been great times to be on the peaks. Or maybe it’s just that I had great times there and the sun was coincidental. Do I need to know? I’m sure in any case that even my slow thaw on Shavano was an enriching experience.

Eventually the transitory moment of sunrise became the steady state of day and we returned to consciousness of our chilled extremities and drooping eyelids. We decided we had better descend before they did. More photo opportunities stopped us a couple times along the way back to our skis (Jason covers a lot of stories like this one and can never get a photographer to come along so he does the work himself). Then, from The Highest Point in Teller County, we skied difficult – but stable – recycled powder slab until back at the trail for a swift snowplow back to the trailhead. We arrived just as some other folks were heading off, at 9 AM – not a bad night’s work!

The morning of March 10th was the dawning of a new period in my life as I put this project to rest and geared up for the next challenge.

February 12 – 2005

Weather is, by definition, erratic and there are many exits off the smooth highway to the summit. Conditions can also change quickly and with little warning; an eye on the horizon is as important as an eye on the forecast, but clouds could be simmering just beyond a ridgeline, ready to boil over into the next basin quicker than cooking a bowl of ramen. In Colorado, it is axiomatic that weather’s volatile — we don’t need no stinkin’ silver iodide, (one of the chemical implements used in cloud seeding that acts like an expectorant on reluctant rain clouds).

When I finally realized the immensity and density of the cloudbank surging across the San Luis Valley, while attempting Crestone Needle last week, I saw no doubt as to its effects or intentions.

This front was preceded by high winds early in the week, sweeping out the last one. I had driven to Westcliffe for an attempt on Monday the 8th, but got nowhere near the mountains. Strangely calm in the valley, the wind was ripping powder off the west aspects and hurling it from the summits and passes of the range in a furious rush. It’s no wonder violence is often compared to storms, tempests…heavy weather.

Ewind is easily the locust plague of the mountains. It descends with indiscriminate ferocity on all the features of the landscape; living beings run for scarce cover, but bombardment with meteorites of ice and lancing jabs of cold can reach just about anywhere. Relentless and unprejudiced, indifferent — nay, callously uncaring — it descends on a land, pummeling and bruising. It doesn’t let up until it has laid down a vengeance worthy of marauding hordes and left an area bent with exhaustion. Until this oppressive wrath returns, the flutings in the snow, pine needles and branches strewn about, remain a reminder — and a warning — of how cruel life can be on high.

I stood there, rubbing my crow’s feet — unconsciously perhaps — where I’d gotten red-then-brown frostburns from Columbia’s winds. Humboldt Peak’s head dress of snow hung out a half mile from the summit and the decision was obvious.

Three days later, I was back, with conditions looking much better, but the forecast calling for snow late the next day. I was again looking through a small weather window and jumping into unknowns to test my speed against the impending storm.

The approach up to S Colony Lakes, for the third time this winter under my own power, was paced to preserve energy for the next day’s climb. Several snowmobiles passed me and this fit perfectly into my plan by packing the road up to the wilderness boundary, which they respectfully observed.

I, for one, am very glad to have areas free of the cacophonous screaming from their engines’ bellies and permeating stench of unmetabolized petroleum. I probably differ from others in how much of this protected land I personally desire, but at least there is a consensus on the need for some Wilderness.

After a more restful bivouac than I’ve yet had (a sleeping pad and can opener being notable improvements), I awoke to the doubled-up darkness of predawn in a snow cave. Then I blinded myself for nearly a minute when I turned on the halogen in my dual bulb Black Diamond headlamp. Its illumination turned the cave into a tanning bed (almost) and I chuckled at the thought as breath vapor curled up to the ceiling I’d iced over with body heat during the night. Two clicks switched to the more energy-conserving LEDs, but still, “I’m awake!” I announced, for indeed the lamp had worked like an artificial sunrise alarm clock.

Next up was oatmeal and hot chocolate. A hot breakfast is essential for the get-go mojo cold mornings require. While the stove kept rolling to fill up my water bladder, I packed up and stood outside inspecting the conditions. The wind had made conditions more orderly, stripping snow from the fetches and depositing it in the lee, so that I could hopefully find one route with one set of gear requirements.

I left the stove at the last minute: I might have taken it to refill my water en route, but was counting on the high overcast to keep me from sweating too much. All I carried in my pack was my pair of La Sportiva North Dome approach shoes –the closest thing to climbing shoes that one could conceivably use in the winter. Or? I’ve done most of these ascents with borderline-inadequate gear (certainly the case on Longs), so who’s to say if someone else might find anything more than gym slippers excessive?

This winter has had manageble avalanche conditions since about mid January, and I saw good conditions on the way to Broken Hand Pass, having inspected a few small, protected slopes on the way up. There is a bowl one must pass through to get to the pass so crossing potential slide areas is unavoidable. The only other option would be to tackle some of the technical rock that borders the snowslopes. I didn’t feel the risk of attempting an onsight, solo, winter climb of the Ellingwood Arête was prudent. Besides, I told myself, the peak is what I came for, not the climbing. In a pragmatic frame of mind, with a subdued ego, I was in the right place mentally for the decision that day.

That decision was precipitated by a suddenly descending cloud layer that moved in just after I reached the pass. I had my head down grunting through some of the worst snow-groveling out there conditions so frustrating because not even digging a trench in front of me helped.

In one spot, I stepped from a thigh-deep posthole to a marginally supportive pocket where I only went shin-deep, but my next step had my uphill foot glance off a sun-glazed windcrust. My body twisted, following the momentum, and I ended up on my back, lying sideways across the slope, and sliding. Instantly, I had velocity. Getting to my self-arrest position with a prestissimo movement still took long enough for my speed to increase ten-fold. As soon as I began to self-arrest though, the crust ceased and I sunk into more deep snow. Thanking my luck, and newly aware, I resumed the slog; of course the crust was slippery something treacherous, but it broke any time I tried to kick holds in it for ascent.

Almost the entire summit pyramid of the Needle was obscured at this point and I became fully aware all at once of the thick, dark-grey bank to the west, the swirling snow and decreasing visibility. The decision, like I said, was easy and it’s good that it was. Attempting to game the weather or ride the margins in iffy weather can get you in trouble, but here the facts were plain. I wouldn’t be climbing unfamiliar technical ground with limited visibility and the possibility of worsening conditions hitting the peak with me yet further from my bivouac equipment.

This retreat marks the first time I’ve had to turn around on a peak and it feels good to have done it. I’ve been waiting for it to happen and was surprised that avalanche danger wasn’t the cause as I’d been expecting. Returning empty handed, once again, leaves a bitter aftertaste, but the options are unthinkable. My goal is to encounter my limits on these peaks and my ego is tempered by admitting the reality of the situation. In the future, thankful that there is one, I’ll be using the experience to refine my judgement on the next attempt.

February 5 – 2005

It took many phone calls, a faxed map, a signed waiver, and $100, but Carlos, the caretaker for Cielo Vista Ranch met us at the gate just after first light. Formerly the Taylor Ranch, it was renamed Cielo Vista (“heavenly view” in Spanish) by the Texas partnership that bought it from disgraced Enron exec Lou Pai. Reportedly, the 70,000+ acre ranch was purchased for about $10 million, so it will only take 100,000 climbers to return their investment. Actually, the $100 fee goes to maintenance of the ranch and the peak. Consider it an investment in sustainable access.

Also consider that the ranch operates mostly on hunting revenues which are easily one hundred times greater than those generated by peak baggers. Then again, these two interests both make keeping the property in pristine condition a high priority for the ranch managers and Culebra is arguably in better condition than some of the publicly owned fourteeners. Another point to remember is that the peak was almost completely off limits while Pai owned it and Grand Slammers should rejoice that the new owners are more reasonable. I was prepared to skip Culebra for ethical and monetary reasons, but found the fee preferable to the lingering thorniness of having to justify a truncated Grand Slam.

Four of us had come from different points of the compass, converging for the rare occasion. Suiting up, we got to know one another. Besides myself, there was Joe Burleson, on his own (more leisurely) Winter Grand Slam quest. He has now collected 41 winter summits. We also had two friends from the School of Mines along: Jay Ivanec and his friend Mack. Jay had completed 53 ascents between Feb. 7 and mid-June during the deep, wet spring of 2004. Now, as of Feb. 5, 2005, he’s just completed the Slam, mostly on skis, barely inside a one year period. Two days later and he wouldn’t have made it. He flew up from Tulsa specifically to make the climb. Mack, who had been on many of the ascents in Jay’s quest, was there to video the moment for posterity (Jay’s at least).

So, overcast skies kept the chill in and the sun out while we mounted up and headed out, but soon burned off and we had a day of bountiful sunshine. Carlos supplied us with a radio, since cell phones are useless in this isolated corner of Colorado, and off we went.

We traded trail breaking all the way to treeline, then I took over breaking and finding the trail (Joe was getting over a cold; Jay had been living in Tulsa for the last six months). Mack turned back because he felt sick. The rest of us kept plugging, motivated by the drive to complete the quest. The C-note we dropped just to have a shot at the peak probably figured in as well. While our clouds had broken up, I’m sure the thought of repeating the cost and effort of an attempt has caused other peak baggers to push on in the face of building thunderheads. There are neither refunds nor summit guarantees, even when paying sixty large for an Everest expedition.

The scenery on the ranch and the peaks around Culebra is superlative. One can look south down the Rio Grand rift valley into New Mexico, west to the San Juans, north to the Blanca Group and the rainbow arc of the Sangres, and east to the Spanish Peaks with the Great Plains stretching beyond. The money and rigmarole, but also the rarity of the occasion – one I probably won’t repeat in my lifetime – made Culebra one of the more memorable peaks thus far in my project.

To cap it off, we four had a celebratory dinner in sleepy-to-the-point-of-hibernating, winter-locked town of San Luis. Enjoying Colorado’s high country while coexisting with those who live there is another of the pleasures to be found on a Grand Slam quest. Remember to respect the people as much as the land when you visit so that those who follow can find the same gratification that you did.

February 3 – 2005

Mount Harvard in a day, in winter? Dawson’s Guide says it’s out of the question. Maybe he’s right about a day, but a half day is certainly doable! Hence my own 12-hour trip.

Slowed by having done the Huron hustle, a total of 24 Miles over the last two days, I got to the top of Harvard at around 8 hours and back down a few hours after sunset. Funky, inconsistent crusts made skiing difficult.

I think I’ll be known more as the guy who forgets his headlamp all the time, but this time I left it on purpose. I thought I’d be back before dark. I swear! So I used the backlight on the GPS to make up (partially) for the lack of moon or LED. I owe another big Thanks to Dave, who lent me the GPS!

Harvard is a long slog, no doubt, very scenic, and requiring good routefinding, but not very interesting. Dawson’s phrase “just another huge Sawatch fourteener” jumps to mind. I’m glad this will be my last peak in the range, except for the exceptional Mount of the Holy Cross.

Climbing and backcountry skiiing on Colorado fourteeners.

Hamish changing from ski to speed boots.

Topping out at 14,420’, Harvard contrasts with Huron at 14,003’ a day before in about the most drastic way achievable among the fourteeners. Harvard is third highest, while Huron is second lowest. How much difference does that last 400’ make? One answer is: half an hour, but let me ask you, if you’re at 13,400’, would you rather have 600’ to go, or a thousand? Once 14,000’ is reached, the summit follows pretty soon, Harvard’s just takes a bit more time coming.

There are some boulders and slabs near the summit that, along with the precipitous west face, make the last bit more interesting. Mostly though, I am yearning for the real climbing of the Sangres. The Sawatch rivals the Sangres for grand scenery, but just doesn’t have the same gaze-bending gravity of sharp spires and sheer alpine walls. Nevermind that the ascents will be intricate and interesting.

Though I hurry, it looks like I won’t make it back to Colorado Springs for the slideshow at the Mountain Chalet with Gerry Roach. He’s a world famous mountaineer and, incidentally, the other fourteener guide author besides Lou Dawson. I really should be there, but as I drop down the CFI trail, take the bridge over North Cottonwood Creek’s tranquil waters, and fall into the kick and glide trance, while backcountry skiing I bask in the sense of accomplishment and relief. By the time I’m back at Tetonka, I’m filled with pleasantly alluring anticipation of the future, dreaming of pulling on cobbles in the Crestones.

January 30 – 2005

Well, I just tagged Humboldt on Jan. 29, taking advantage of a tiny weather window perhaps no longer than 18 hours. I camped at the South Colony Lakes trailhead down in the Wet Mountain Valley, 2000 vertical feet and about 4 Miles from the summer trailhead. I’ve always hiked in from here anyway, since I never seemed to have a 4WD vehicle with me.

The clouds seemed to be lifting just as it got dark. I was reading and listening to the radio in the cab, relaxing while I cooked some not-low-carb pasta for dinner.

That radio is a $14 Radio Shack model, and the headphones are equally non-descript and cheap, but they have hidden strengths. I mean it. When I started up towards Belford last week, I turned it on at the truck and got nothing. Not meaning no reception, but deadness. The radio does things like this often – playing possum, random clicking, a sudden forte-pianissimo crescendo – so I figured it was just being its ol’ uppity self. “I guess this will be a radioless trip,” I sighed and took off the headphones. Since I had already locked up the car and stashed the keys in my pack, I decided to just leave it wedged in between the camper and the cab, sticking partway out so I would notice it upon my return.

Of course, I forgot about the radio until I had driven all the way back to Colorado Springs, and at that point I figured it was just gone, so I didn’t even look. Well, when I got to the trailhead for Humboldt, a week later, I noticed something hanging down under the truck. Sure enough, coated with mud and road grime, the headphones had been dragged along over a couple hundred miles. The radio was wedged firmly in between bed and cab and with fresh batteries and a little drying out, the whole ensemble went back to work. “Right where we left off, “I thought to myself, referring to the radio, but also to the peaks.

Starting off from almost the lowest point between the Sangre de Cristo and the Wet Mountains, I gave thanks for that radio. Remarkably, there were several radio stations to choose from and they stayed with me all the way up the Colony Creek drainage. This was much better than the other times when I only had Rush Limbaugh or static to listen to – both white noise if you ask me.

My start was early, but not exactly alpine, and I skinned along an old track left by none other than Tom Mereness and friend two weeks before. Tom was the first to ever complete the Winter Grand Slam and he is now repeating some of those climbs to help a buddy, Joe Burleson, on his own quest. The track was a little buried by the one storm we’d had since then, but the new snow had kept well allowing my skis to slice the champagne as if it was still suspended in the air. The road is moderate so one can gaze ahead at the increasingly dramatic vista of the S Colony Lakes basin. Each new piece of grandeur is revealed in parcels.

Skin, skin, skin.

Striking, unnamed thirteener (the summer trailhead is directly below this one).

Skin, skin, skin.

Broken Hand Peak.

Skin, skin, skin.

Oh my gawsh! Crestone Needle.

I gawked and gasped as I have every time I’ve been up there, indeed as I would just about every time I glanced over at them for the rest of the day. The weather was somewhat unsettled and clouds would build up, then stream off the Crestones all day long and I was frequently mesmerized. I would hold my camera up to my eye and just stare. More images were committed to memory than to film that day.

The reason I chose to head up here today, even though Friday’s forecast was snow showers clearing in the evening and Saturday’s was snow in the afternoon, was what I heard from the CAIC. They predicted a storm would move through from the southwest, and then retrograde back to the southwest, causing an upslope to develop. Therefore, I reasoned, there would be a small window where the winds slacked and clouds burned off while the system reversed course. I aimed to summit before the upslope started blowing up against the east side of the range.

As I arrived at the lakes, it seemed my timing was perfect: sun shone on Humboldt, huge sucker holes opened up, and the volcano-like plume lifted off the Crestones. Somehow I managed to swing nearly still air and partly cloudy skies all the way to the summit.

There was the small matter of the steep slope from 12,000’ to 13,000’ on Humboldt’s W Ridge. This slope had collected a bit of snow from the storms and, since the snowpack had been undergoing drastic changes in the last week or so, I dug a hasty pit. Here’s what I found:

About 2 ½ – 3 feet of snow where I dug, although that was probably about the deepest on that slope. Faceted crystals at ground level, as is usual for Colorado, ranging in depth from barely a schmear to 4” next to a buried rock. On top of this was the result of the recent extremely warm spell. Namely, a melt freeze crust of moderate strength (it was certainly frozen today) up to 18” deep, composed of large, rounded grains. Six inches of fresh on top of that, with about three inches of wind-transported soft slab on top of that. This top layer was the only one I got to shear in a column test and the bond between the crust and the new snow seemed to be quite good.

Go for it? Not until I tried to ski cut a few small, steep slopes nearby, with no results. I felt confident in the snow, but found a silver lining to not having my radio. That way, I could pay closer attention to the slope, in case it did any talking.

My stomach was talking; I forgot two triple-decker PB&J sandwiches in the truck. At least that compensated for carrying the extra layer I wouldn’t use all day. My total rations consisted of two CLIF bars, five CLIF shots, and some Twizzlers, but they were for a gag summit shot so I resisted. Upon arrival, I composed the shot: Twizzlers in ears, nose, sticking out of mouth and clenched between squinting eyelids. I even started a slight nosebleed forcing the cold-stiffened licorice into my dry nostril, but I was hungry and – y ou’re darn tootin’!– I ate them all, blood, boogers, and earwax be damned! One must sacrifice for art’s sake!

A short, stumbling saunter down to my stashed skis, then a sweet swish of stem-christy turns brought me back to the valley floor. I ogled the Crestones one more time, thankful that I would return to climb them soon, and then slid off home.

Apparently my timing was perfect on the weather. The summit of Humboldt is a mere six bird miles from where I parked and, by the time I returned to the half-buried Teton, it was snowing hard enough to air-condition Vesuvius. It’s impossible to see ahead with a headlamp in these conditions because all you see is a curtain of illuminated snowflakes. My solution was to put my Zipka on my hip belt. Although I cast strange, insectoid shadows, my vision was much improved.

Forced to drive at a crawl through the driving snow, one thing was clear: I was sure to have a day off to recover, and to dream sweet dreams of returning to those fantastic Crestones.

previous logbook

Checklist

Attempt at 54 Fourteeners In One Winter (04/05)

(completed peaks have date)

December

21 Longs (North Face) (#1)

24 Bierstadt, Evans-Guanella via Sawtooth (#2,3)

25 Grays, Torreys (from Loveland Pass) (#4,5)

26 Quandary, Democrat, Lincoln, Bross (#6,7,8,9)

27 Mount Sherman (from Leavick) (#10)

31 Mount Princeton (#11)

January

1 Antero (#12)

2 Shavano, Tabeguache (#13,14)

7 Mount Yale (#15)

12 Mount Columbia (#16)

15 Mount Elbert (#17)

16 La Plata Peak (#18)

19 Mount Massive (#19)

22 Mount Belford, Mount Oxford, Missouri Mountain (#20,21,22)

29 Humboldt Peak (#23)

February

2 Mount Huron (#24)

3 Mount Harvard (#25)

5 Culebra Peak (#26)

March

10 Pikes Peak (#27) … last peak of project

Peaks that didn’t get done:

Mount of the Holy Cross

Crestone Needle, Crestone Peak, Kit Carson

Lindsey

Little Bear, Blanca, Ellingwood

San Luis

Redcloud, Sunshine, Handies

Uncompaghre, Wetterhorn

Sneffels

El Diente, Wilson Peak, Mt Wilson

Eolus, Sunlight, Windom

Castle, Conundrum

Pyramid, N Maroon, S Maroon

Snowmass

Capitol

Beyond our regular guest bloggers who have their own profiles, some of our one-timers end up being categorized under this generic profile. Once they do a few posts, we build a category. In any case, we sure appreciate ALL the WildSnow guest bloggers!