My DIN is bigger than your DIN.

A slope inclinometer used to be the skier’s macho meter. Is obsession with DIN numbers the new gauge? Is the max DIN of a binding any indication of quality or durability? Is a “DIN 12” skier better than a “DIN 6” skier?

What we skiers call “DIN” is a standardized and calibrated rating of how “stiff” the release (or better stated, the spring loaded boot “retention”) of a binding is set to. The term comes from a German standards organization, more here.

It’s important to know that not all ski binding release settings are truly “DIN.” To be so, the binding must be certified as compliant with the DIN/ISO international standard. This is usually done through a company in Germany known as “TUV.” While virtually all alpine bindings are TUV certified, as well as many frame type touring bindings, only a few frameless “tech” bindings are certified by TUV to the DIN standard. Therefore, the numbers you see on your tech binding are not necessarily “DIN” numbers, they are simply “release-retention values” that may (other than in the case of certified bindings) approximate DIN settings at the whim of the manufacturer. Thus, we call them “RV” numbers here at WildSnow.com.

Check this out for more about DIN ski touring binding issues.

Enough discussion of definitions. The point of this blog post is that maximum DIN or RV number on a binding is NOT a rating of binding quality. Nor is a high number an indication of how good a skier you are. Nor will it make you ski better.

Also, a common misperception is that a binding with higher maximum DIN is somehow more resistant to unintended release (prerelease) — no matter what DIN the binding is set at. Worse, skiers sometimes assume they can crank up to a higher release settings to prevent prerelease — with no consequences.

Having a higher available DIN/RV can indeed be useful if you need to adjust the binding to higher numbers because you’re bigger or ski aggressively and inadvertently pop out of the binding (prerelease) at lower numbers. More, if you ski out of the gamut of normal performance, say you’re a racer, cliff jumper or exceptional freerider, you may need a binding with higher available RV/DIN numbers.

In the case of no-fall terrain, the idea of super-high settings is 100% valid. Bindings should be cranked up to high numbers or locked out (or both, if lock is available) — and you should be qualified for the terrain.

But tuning a binding to NEVER prerelease in normal skiing is a different matter.

Problem is, if you exceed the upper level of settings as indicated by the DIN settings charts used by ski shops (see below), it is quite likely you’ll be injured in a fall due to your binding not releasing. Nonetheless, the valid argument in favor of over-cranking release settings is that falls resulting from prerelease can be hideous — especially in no-fall terrain.

The DIN chart settings may appear low, but they actually do work for a lot of people, especially at the Type 2 and Type 3 skier settings. But what if you need to go beyond that? A common approach is to just grab the screwdriver and crank the binding as far as it’ll go. Perhaps that’s valid, as the point of the exercise is to 100% eliminate prerelease, and any settings above the charted DIN standard are dangerous anyway. But I still recommend a more nuanced approach; if you need to go above the chart recommended setting only increase one number at a time, then ski. In my experience, unless you’re doing something like slamming cliff landings on ice, a binding setting that’s one or two numbers above the chart will work for nearly anyone.

Beyond DIN/RV settings. Know that the elasticity range, return to center force, anti friction mechanics and general engineering of a given binding are equal if not more important to binding retention and performance than the DIN/RV setting. For example, many versions of tech bindings have minimal vertical elasticity at the heel. That means you need higher release settings for aggressive skiing, which will conversely make the binding less safe.

Be it known: If you’re needlessly setting your DIN numbers at the max you might indeed get something to brag about over beers, that something being the new macho meter you bought for your orthopedic surgeon — his Cessna.

Comments, anyone?

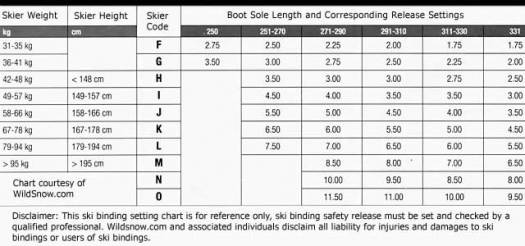

Choose your “Skier Code” using weight and height, then follow line to right and choose DIN that corresponds to your boot sole length. IMPORTANT: Pick your skier type below, then use following correction factor: Type 1, no change. Type 2 go one step higher, Type 3 go two steps higher. Age correction: If over 50 years old reduce setting one step. To be safe, have your binding settings checked by a qualified technician at a full-service retailer.

Skier types: Type 1: Careful skier preferring moderate terrain, or a beginner skier. Type 2: Skier preferring average speeds and somewhat difficult runs. Type 3: Few skiers in this category; racers, extreme skiers, prepared to take risks, ski at high speeds. Most backcountry skiers are Type 2.

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.