Bil Dunaway

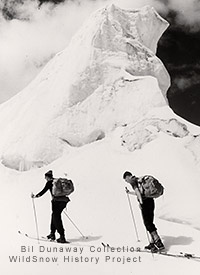

Terray and Dunaway head up Mont Blanc in 1953.

In 1953 few people thought it was possible to ski down the north glacier of Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest mountain. Although hundreds of people climbed the 15,600 foot peak each year; since 1786, when Saussure and Balmat first reached the top, thousands had braved the icy winds, the steep glaciers, the knife ridges to make the arduous two day climb, few had ever skied back down — and none the hard way.

When Lionel Terray said it could be done they wondered. Terray was one of France’s best alpinists. He had conquered the north wall of the Eiger in Switzerland, the north face of the Grandes Jorasses in France, he had been on the French expedition to Annapurna and had made the first ascent of Fitz-Roy in Patagonia, but this was different. Everybody could see from Chamonix that the north glacier of Mont Blanc was too steep, too full of crevasses to ski down.

Terray decided not only to ski down but to film the descent. The movies would go well with those of his previous expeditions. But for this exploit he needed another skier. He wondered who would be crazy enough to try with him. He asked me. I like the idea, and plans were made for a Franco-American attempt in late May.

[Editor’s note, here at WildSnow.com we write the names Dunaway & Terray in alphabetic order as they were equal partners in the endeavor, not guide/client. Above paragraph alludes to Terray’s other movies. At the time, he was attempting to do the movie lecture circuit to fund more expeditions.]

While waiting for the photographers to come from Paris Terray and I checked our equipment. We were both veteran skiers but we realized that among the bottomless crevasses and towering ice walls of the high glaciers a fall would be dangerous — we wanted to live to see the movie when it was completed. The photographers were also mountain men, they had to be to get within camera range. Jacky Ertaud had often worked in the mountains as well as underground on cave explorations and underwater with Captain Cousteau and his research group. Gerard Geri was a licensed guide as well as a cameraman. Both welcomed the chance to leave work in the city to join us in the mountains.

Editor’s note from Lou: When Bil helped me with my Wild Snow history project back around 1995, he said to use this any way I saw fit. It took a while, Bil is gone, but I know he’d be glad to see this presented here as historical record for everyone to enjoy. Lightly edited for clarity and brevity. Please see our previous post about Mont Blanc 1953 ski descent. Regarding the photos, they were given to me by Bil for the same purposes, he said he had permission to use these work-for-hire movie stills of himself for any publication he saw fit. The photographers are probably either Georges Strouve or Pierre Tairraz. I’m researching the photo origins and permissions and will adjust if necessary. Also, please note that the first ski descent of Mont Blanc is known to be that of Armand Charlet and Marguette Bouvier in 1929. Terray and Dunaway’s descent was the first of the peak’s steeper northern reaches.

The weather seemed against the adventure. It was sunny when our party left the valley; with two cameramen, the porters and the two girls, Mrs. Terray and ski champion Suzanne Thiolliere, who were to add pulchritude to the shots of the climb. There were eight of us; and it was sunny all the first and second day as we climbed the lower glaciers to the Grands Mullets refuge and filmed the climb. But on the afternoon of the second day when we reached the aluminum shell at 14,000 feet that is the Vallot refuge, the sun was gone. The girls just had time to start down with the porters when the clouds swirled in and attacked the mountain. An hour later everything above 13,000 feet was buffeted by storm.

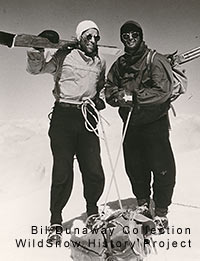

Terray (left) and Dunaway doing the 'man spoon' at the Vallot hut. 'Water froze ten minutes after it boiled.' Used by permission of Bil Dynaway for historical purposes, photographer unknown.

For four days we shivered in the aluminum hut. Wind rattled the metal sheets, drove snow dust through the joints. Water froze ten minutes after it boiled. The very steam from the tea was cold. Fully clothed, wearing down jackets, nestled in down sleeping bags under piles of wool blankets, we kept warm, but we seldom left our bunks. After five minutes on the cabin floor our feet and hands began to hurt. It was hard to cook. Our hands were cold even while touching the hot pans on the butane gas camp stove. The only water came from melted snow. Our toilet was a tin can emptied into the wind. There was no question of leaving the hut. Outside the wind made it impossible to stand, difficult to breathe, and hoar frost and wind driven snow plastered everything.

After four days the wind abated but the clouds did not clear. Preferring the risk of dropping into a crevasse in the fog to running out of food, we decided to ski down. The valley, even in the rain, was welcome. Dirty, bearded and hungry we appreciated as never before the chance to bathe, eat and relax in weather that was not freezing.

A week later the sun reappeared. Rested and impatient to continue the movie, we again left the valley. This time as six in number including two assistant cameramen, we climbed to the Vallot refuge in one day. The weather was fine and Ertaud and Geri filmed many interesting climbing shots.

During the night, however, the clouds gathered, and the next day the mountain was again in storm. This time we waited six days; six days of wind, snow and cold. Six days of taking camera equipment and boots to bed to keep them from freezing, six days of melting snow for water, of eating half cooked noodles and canned meat. Six days of misery without being able to ski or take pictures.

When the food ran out there was over two feet of new snow, and avalanches thundered from all sides. It was foolish to go down in the fog with the new snow, but we were hungry. Slowly with the caution of blind men, hearing each sound, sensing each vibration, we felt our way. One slide would bury us forever, and they crashed all around us. Terray, the most experienced, went first. With nervous perspiration dampening our clothes, we watched him pick his way down each slope. There was no question of skiing. That was too dangerous. What had taken us an hour to descend on skis now took us six on foot, and each step was a strain.

When our friends in Chamonix saw us they greeted us profusely. Terray’s wife was in tears. They too had heard the continual roar of the avalanches.

For the moment it looked as if the film was over. The weather stayed bad. The two photographers left. Terray, however, was steadfast. Other photographers could be found, the weather had to change sometime. He waited.

July came and with it came good weather. Terray contacted all the mountain photographers he knew. What was required was almost superhuman. We needed two good cameramen who could not only climb the mountain but also work among the seracs and crevasses of the high glaciers. Then for the first time fortune smiled. George Strouve who had filmed the successful expedition to Fitz-Roy finished his current job and accepted Terray’s offer. With him came Pierre Tairraz. Our expedition reformed. We rechecked our skis, repacked our sacks. Again we climbed to Vallot. This time, however, we were not alone. A constant stream of alpinists wore a groove up Mont Blanc.

The next day, Sunday July 19, our stream of bad luck continued. The weather was good throughout Europe except at the summit of Mont Blanc. Here a circle of clouds covered the last two hundred yards. The descent would have to wait. It could not be filmed in the clouds. But a ski movie is not all distant shots and Strouve decided to film scenes of us jumping crevasses. Near the refuge was a magnificent specimen. Fifteen feet wide, it was hundreds of feet deep. It could be jumped, but on the other side there was less than a hundred feet of landing hill before an eighty foot ice wall. Below the ice wall was a steep snow slope two hundred yards long ending in a thousand foot cliff which dropped off into Italy.

“We can do it,” said Terray. “It’ll look good on film.”

I was less certain. I didn’t like the landing, but I followed him up for the short run before the jump.

He pushed off, made two turns, then leaped. Sailing through the air, he cleared the crevasse nicely. I followed.

“Nice jump. Let’s try again where it’s wider,” said Strouve.

Terray climbed up to try again. This time he jumped farther. His body was graceful against the blue sky, and he was in the air for a long time. When hit hit he landed on icy snow. For an instant he rocked unsteadily, then he fell.

Everyone watched. He fought to regain his feet, but he couldn’t stop himself. Suddenly with no noise, before we could realize what had happened, Terray was gone. I gasped and felt sick. Everybody turned pale. We knew what was over the crest, the ice wall, the steep slope, then the cliff.

I skied down as close to the edge as possible, then side stepped to the brink. Below, a black spot on the snow, was Terray. He had stopped before the drop off.

“He’s alive,” I shouted, “let’s find a way to get down.”

Two hours later, smothered in three sleeping bags, Terray was drinking hot tea and cognac in the refuge. Except for some very sore muscles he was unhurt, but the reaction made him shiver as if with the ague. He had fallen free over eighty feet, then bounced and rolled a hundred yards. It was miraculous he was still alive. His fall was luckier than that taken by the camera. Dropped when were were trying to reach him, it had disappeared over the edge and was now thousands of feet below in Italy. In it was the film of his fall.

That night to continue our luck the weather turned bad. The next morning the wind again pounded at the aluminum plates and the clouds swirled past with express train speed. When we heard the wind we snuggled into our bags and forgot about skiing. Not for long, however. Before we had time to breakfast five Spanish climbers came in. Muffled to the eyes in many layers of clothes and plastered with snow and frost, they filled the refuge with life. Talking and laughing, they drank the hot tea we offered and joked about the French weather. After asking us questions about the climb, resting an hour, they adjusted their equipment and set out. They were vibrant with health and the desire to reach the top.

Five minutes after they left one of them came back. He was too tired to continue. The others were never seen alive again.

We worried about the Spaniards all day. They had been foolish to venture forth in that weather. As hour followed hour our concern grew; and with it grew the intensity of the storm. At five in the evening we decided to do something. Pierre Tairraz and I left our sleeping bags, put on all our clothes, strapped on our crampons, tied into our climbing rope and left the refuge.

The instant we stepped outside the storm beat into us. We could barely stand against the wind. The driven snow and the sleet cut at our faces, hammered on our parka hoods. We started up the ridge. As we climbed the wind increased. Frequent gusts knocked us prone. Our progress was slow. Often we had to pull ourselves forward on our ice axes driven into the snow.

For two hours we advanced, painfully, slowly. The storm increased as we gained altitude. Finally it was no longer possible to crawl. We were forced to lie flat on the ridge and pull ourselves along. I blew on my whistle as often as possible. The wind tore out the sounds before they reached the air. it was impossible to continue. We turned back.

Two days later the frozen bodies of the four men were found hanging from their rope where they had fallen from the ridge, fifty feet from where we were forced to turn back.

During the night the storm ended and the next day, July 21, dawned clear. We spent the morning combing the ridge between the refuge and the summit, hunting for the missing climbers. When nothing was sighted, we decided to continue our film.

Thinking of the missing Spaniards, our spirits were low that afternoon as we carried our skis to the summit. Pierre Tairraz accompanied us, filming our arrival at the summit with one camera while Strouve stayed on the ridge halfway up with the other. The north wind was cold, blowing the snow off the ridge like smoke. Sheltered in a choked crevasse near the top, we made last minute adjustments to boots and clothing. My hands shook with cold and excitement and under the strain the three of us chattered like children. We had waited a long time for this opportunity, but in my heart I was not certain I was ready.

Dunaway (left) and Terray at Mont Blanc summit, July 1953.

Less than forty minutes after reaching the top we stood looking down at Chamonix. It was very small and far away. Down there it was warm and people were happy and gay, fruit hung from the trees and the fields were dotted with flowers. Here there was nothing but ice, snow, wind and sky. Our skis overhung the summit cornice. Under them the slope, crisscrossed by ice falls and crevasses, fell away steeply. To one side Pierre prepared to shoot our departure.

“Okay,” he said. “Good luck.”

“So long,” said Terray and pushing on his poles he dropped off the cornice. I watched him make four cautious turns on the steep, icy snow and felt terribly alone. Skiing on that slope looked impossible. Then it was my turn. The cold eye of the camera drove me forward. I couldn’t turn back. I pushed on my poles. The slope dropped away under me and I was skiing.

Once the movie was made, both Terray and Dunaway toured it around. Once Dunaway lived in Aspen, he showed it regularly at local events.

The snow under my skis was wind rippled and icy, but it was good to be in action. Forgetting my doubts, my fear, I concentrated on skiing. The steel of my edges bit at the snow, held. I could do it. Suddenly I was full of confidence, and driving forward, I swung into my first turn. 15,000 feet below me was the dark green of the valley, but directly below was Terray. He looked up and smiled and I knew we would succeed.

Two hours later we came to a stop on the “grand plateau.” Above us the seracs, the crevasses, the ice falls of the north glacier were laced for the first time by ski tracks. Shouting and laughing, we congratulated each other and waived to the cameramen on the ridge so far above. Our happiness could not be expressed. That which people had said was impossible had been done. The first ski descent of the face of Mont Blanc was ours.

*********************************************

It is possible (though expensive) to purchase the film Dynaway and Terray made, check here.

Beyond our regular guest bloggers who have their own profiles, some of our one-timers end up being categorized under this generic profile. Once they do a few posts, we build a category. In any case, we sure appreciate ALL the WildSnow guest bloggers!