“Shhhussssh, shushhhh, shushhhh slide my skins. My brain swirls and twirls, twisters and helicopters. Jumps I haven’t done in decades and never will again. My skis skim the surface of the snow.”

I fumbled through maps, trying to remember when I got old. I don’t know how it happened. But one winter a long time ago, I considered myself a real skier.

Real skiers go fast and rip turns and huck cliffs. Daffies, twisters, and—the trick that makes time stand still—the glorious, soaring, spread eagle. My favorite, though, was always the backscratcher. I don’t know why. Regardless, another lifetime ago, in the winter after high school, I stumbled upon a job at Keystone ski area in Summit County, Colorado. The epic and ikonic vamps of corporate America had yet to suck the soul out of ski hills, and, as with most young people, I was thirsty for life experiences.

“Do you like to go fast, Kelly?” my boss asked in the base lodge kitchen on my first shift. It was 1987, and saying yes seemed like the cool thing to do, and so after work we tucked down a closed run in the dark without headlamps (it was so long ago, maybe they hadn’t been invented yet). A second after we stopped, a ski patroller poached our employee passes for a week. After that interminable penalty, however, I skied nearly every day, for months. By the end of the season I made the big time: I worked the BBQ grill outside the summit house. Flipping burgers in the sun. Music, cute tourists, and obligatory turns to finish each shift. I had a pair of red shell pants with tropical print knee panels, made by a local dude selling them from his truck—I shred, in the parlance of my mind.

Best of all, if you made it ‘till closing day at Keystone, they’d honor your pass at A-Basin. So I couch surfed for another month, enjoying spring skiing at its finest, with endless bump runs, itinerant ski bums, and parking-lot keggers. Lifts were king, and the absurd concept of walking uphill never brushed the border of my mind. Why would you walk? Walking was for people who were old and had no friends. We rode up and skied down wearing T-shirts into May.

Shhhussssh, shushhhh, shushhhh slide my skins. My brain swirls and twirls, twisters and helicopters. Jumps I haven’t done in decades and never will again. My skis skim the surface of the snow.

I had found a place. Right there, under my nose on the map, a breath away from the park boundary. That was easy, I think. No bumper-to-bumper lines, no entry gate, no people. There’s nobody here to impress, not that anybody would be impressed by an old man walking uphill, alone, on skis. No bands, no kegs.

I imagine the look of disgust on the face of my 19-year-old self, and I laugh. “Yes,” I say to only the wind, “I am just walking.” Long ago, after that gateway drug of ‘87, I lost interest in lifts and crowds, and grew increasingly drawn toward quieter spaces. This place I call home, a national park town, once was quiet, too, at least in winter. Everything changes, I know, so please forgive me: I fell deeply in love with mountains and wild places before flogging them became a Groupon activity.

I chuckle and whisper to myself. It’s OK. I move some more. My negativity softens. Thoughts and memories flow and fade.

Through the pines I hear the roar of the wind, and glimpse rays of sunlight flickering between branches. Each stride lulls me toward a state of waking dreams. Soon my internal ranting stops and I watch my mind drift to the strangest places, and I begin to wonder why the young seem to embrace so much noise, and then venture so far for silence.

The trees open and the wind howls like wailing voices. I think of the soldiers drawn to the intensity of war, the sound of racecars, and parents rocking crying babies. Then an old man in a rocking chair. I dip my head to shield my face, and when I see my skis my feet are walking across a gymnasium floor toward the ring, my mind rewinding to my college years when boxing consumed me. Competitive bouts always started with so much noise, so much fear. As much as anything, I remember the ring walk. It has been called “The loneliest moment in sports.” You could hear your pulse pounding in your ears. The sound of fans, music on the loudspeakers, coaches urging you on. Then they were gone. No teammates, no out of bounds, no time-outs. The bell rings and you move toward a skilled opponent—trained to go hard and throw combinations and counterpunch. Just like you. In the ensuing intensity, a silent focus emerges. You learn about yourself.

How curious, I think, as if I am watching a ghost. A young person’s game. Flurries begin to fall, and just as my old man shuffle carried me back to the ring walk, the rhythmic motion transports me to another, one inseparable from beauty and fear, the racing mind, the breathing and the risk, the self-talk. And then, the silence.

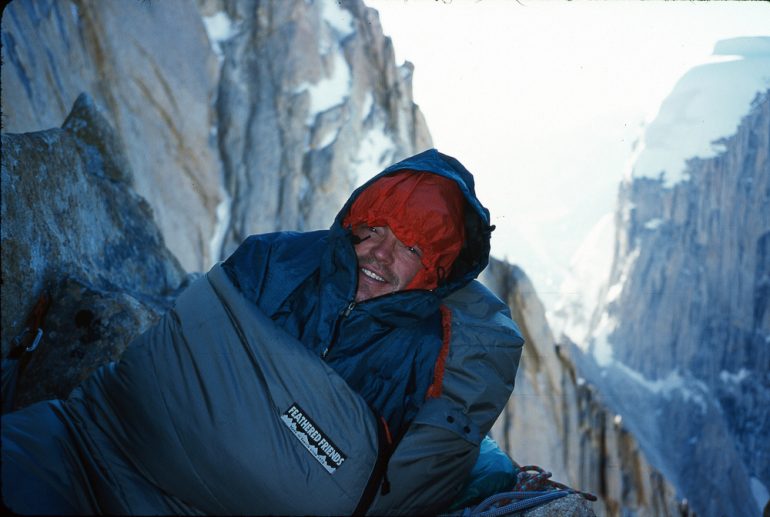

A sloping rock ledge in the middle of Mars. The author settling in for a night on Great Trango Tower, Pakistan, 2004. Photo: Josh Wharton

I always considered the final steps to the base of a big alpine climb to be sacred, the moments divine. I always liked to take the first lead, because the sooner I’d leave the ground the sooner the mental cartwheels would stop. A flash of light through the trees triggers a memory of heat lightning across the desert, hundreds of miles to the south in Pakistan, seen from a bivy thousands of feet above the glacier in the Karakoram, a million miles away from Planet Earth. An image forever etched in my mind. Except it wasn’t only the view, because I could get that from a postcard or a photograph back home, where sensible people were enjoying the warmth of their beds. Why we went to such lengths to find peace, I cannot answer. Maybe it was nothing more than a curse of the gods, a trick of the light that slipped into our souls, to be so blessed and so flawed as to travel so far for silence. But I always remember the nights.

Nights are when most of us sleep, when the world lies silent and beautiful. Infants sleep around 16 hours a day. Teenagers nine. Adults, maybe seven. In “people of advanced age” (talk about a euphemism), both quality and quantity decline, as we journey toward eternal nothingness. But sleep, the elixir of life, is far from nothing. In sleep, our brains and bodies process and organize our waking experiences. We recover, regulate, reset. Sleep consolidates the noise.

I notice snow blowing from the branches, and intricate crystals drifting to rest. I blink and a black screen hovers behind my eyelids, and for a moment I’m not sure if it was a second or an hour. I haven’t slept well in weeks.

For most of my life, I slept like a baby. It didn’t matter where. A sidewalk, in class, a friend’s couch, a sloping rock ledge in the middle of Mars. I’m unsure of what happened, though a seven-year stretch that I reverently call the pain years may have done something to me. Maybe it’s just math because I was already getting old, I don’t know. But Hemingway was right: The world breaks everyone. You have to keep fighting.

The sound disappears in my ears, shushhhh, shushhhh, and I’ve forgotten how long I’ve been walking on skis. I think maybe I should turn around, when suddenly the answer hits me. Quite simply, if you can’t sleep, and older folks don’t, over time our brains get full (scientifically speaking), a phenomenon that grows increasingly damning as fragments form and we frazzle, our minds clogging much like an overflowing hard drive low on usable space, filled with what scientists call space junk. The young suffer no such issues since they can sleep, though they wage battles of their own (just check Instagram). Mother Nature has little use for the old; we are disposable while the young spout and spawn, though in her mercy and grace she allows us to linger, or loiter, so long as we don’t break anything. She is quite busy with greater priorities, so we, the aging, are left to our compensatory mechanisms. Screaming at the sky, drinking excessively, and shouting at the neighbor kids are obvious options, but not the only options.

Thirty-five years after that winter in Summit County, finally I know why the old and the wise walk in silence.

“If I were there and not here, then I would miss the shafts of light darting through the trees, the sensation of floating on frozen water and air, and the tiny, glistening snowflakes that flutter from the pines as I slip and slide through the forest.”

At last I am no longer thinking, and I glide across the snow as thoughts, experiences, and memories consolidate and organize with every stride. Sometime later, it occurs to me that if I were strong, I could find ways to replicate this fulfillment without the crutch of physical movement. If I were strong, I could simply sit on the cushion and stare at the sunflower. Then, perhaps, I would speak more softly and all would be perfect and tidy inside, the way it was when the bell rang or when we left the ground, except that now, after all these years I know the naked truth of the world, it is revealed in the photons of light, and as the forest opens before me I realize what I must do: I stop above a seven-degree slope and rip skins.

I do so in full recognition that I am not yet ready for the cushion. It is too great a battle for me now, one I cannot win and will not try, because if I were there and not here, then I would miss the shafts of light darting through the trees, the sensation of floating on frozen water and air, and the tiny, glistening snowflakes that flutter from the pines as I slip and slide through the forest, the beautiful, quiet forest beneath the mountains, the places where I found life and purpose and calm, where I am nothing more than an old man grinning and giggling like I were young, pulling long, soaring backscratchers in my brain and listening only to the sound of the wind.

Kelly Cordes is the author of The Tower: A Chronicle of Climbing and Controversy on Cerro Torre. He is known for his wordsmithing, alpinism, and his iconic margs. While Kelly is determined to be less grumpy and (maybe) less of a hermit, he claims he can’t do anything about his stature or his skiing.