Skiing the NE Ridge of Foraker, after ascending the Infinite Spur, with basecamp looking a long ways away. Photo: Sam Hennessey.

It’s no controversy, in most circles, to suggest that skiing is more fun than walking. At least, I hope not. In the Alaska Range–and all other cold, snowy places–it’s not only more fun, it’s safer, faster, and exponentially more energy efficient both on the way up, and of course, on the way down. This is self-evident: to move effectively through the mountains there, skiing proficiency is a must.

Michael Gardner and I are mountain guides based out of the Rockies–Michael in Victor, ID, and me in Bozeman, MT. We each have a major soft spot for the Alaska Range, and have been guiding and climbing there for the last decade. Yet, for us, having fun and maximizing adventure is far more motivating than speed records or climbing/skiing the “hardest” route. Those sorts of goals come naturally if you are psyched about stepping into the unknown. We both probably identify more as climbers, although Michael used to be a professional freeskier, and you’re way more likely to find me at Bridger Bowl on my days off than out at the crag.

Recently, we had an adventure in Alaska that wasn’t so much about walking a tightrope of risk, but about envisioning technical alpine ascents paired with ski descents that would keep us honest. With this perspective, an already tantalizing range became more interesting.

Rest and recovery on Denali’s Cassin Ridge. Photo: Michael Gardner.

Reimagining the Alaska Range for us started in 2018. As the season kicked off, the weather just wasn’t cooperating. We sat in Talkeetna in the pouring rain for almost two weeks, only to fly into the range and sit again. We were not deterred, however, from enjoying ourselves. We had a ton of free time to lay in the tent, stare at the ripstop, and come up with stupid ideas–we excel at this.

We derived the wildest traverse we could think of: Climb the Infinite Spur on Mount Foraker, ski down the north side, and then packraft across the tundra for 60 miles to Lake Minchumina. Multi-sport wilderness adventures are common in Alaska, and so we figured it was logical to throw alpine climbing into the mix. Our mental mapping from A to B (the summit) to C raised the question of what would be easier: climbing hard in ski boots, or skiing hard in climbing boots? We debated the pros and cons, and I was ready to spend the next season at Bridger in my Silvrettas, dorking out and preparing to go big.

For those without the pleasure of having experienced these bindings, Silvrettas were the original backcountry ski binding; versions manufactured in the 80s and 90s are still a go-to for skiing in mountaineering boots. High performance they are not.

Back from Alaska, at home, we couldn’t stop thinking if the climb-ski-packraft epic would be possible, and began to tinker. We knew that climbers frequently do all manner of technical ski mountaineering in the Alps, as well as the rich history in Alaska of single-push climbing under the midnight sun. Not to mention the recent history of radical ski descents done in perfect style, like Andreas Fransson’s solo descent of the South Face, and Peter Dale and Aaron Mainer’s top-down onsight of the Wickersham Wall. With our background in alpinism, we figured such mega traverses weren’t too far “out there”–it was just a matter of figuring out the proper setup.

Admittedly, we were a little behind the times when it came to gear, and were unaware of just how light and reliable skimo racing equipment had become. The crux of the whole endeavor was always going to be boots. I learned to ice climb in ski boots back in college…it wasn’t exactly ideal. Those were alpine boots, though, and when I first went climbing in my shiny new Alien RS that winter, I couldn’t believe how well they performed.

I’ll detail more gear specifics in a later article, but when combined with race skis, skins, and fixed-length poles, our ski kit didn’t make our packs significantly heavier. Because we’d learned to strip away other unnecessary equipment, our packs were still probably lighter than what I once carried on a day climb in Alaska six or seven years ago. The evolution of this light, durable ski gear made climbing in single-push style with skis reasonable, and the way down still fun, once you got used to it.

Adam Fabrikant finds the way, low on the NW Buttress of Denali. Photo: Michael Gardner.

Proof of Concept

The next Alaska climbing season, in 2019, we succeeded in climbing the Infinite Spur, and then skied down the Northeast and Sultana Ridges, and Mount Crosson to get back home (we’d thankfully been talked out of the packrafting idea). It was a wild ride, and far more fun than walking! Plus, it served as a nice “proof of concept” for our idea of bringing skimo tactics to big alpine routes in Alaska.

It wasn’t just a novelty, either: the skis made us faster–way faster. And in the mountains, that translates into less time out, less time exposed, fewer calories to burn, the whole deal. Not to mention, we didn’t have to walk back to the base to retrieve our skis, create garbage by chucking skis into a crevasse, or embarrass ourselves by wearing snowshoes. And finally, there’s a certain elegance to the concept, especially when making a traverse of a big mountain, that got both of us super psyched.

We stayed out of Alaska in 2020 due to Covid, although I still drove myself crazy remotely scanning daily weather forecasts.

We came to realize that there were quite a few objectives, both in Alaska and closer to home, that made perfect sense to approach in this style.

To start, any route where teams routinely throw their snow-flotation (read: skis) into a bergschrund, or make lengthy trips after climbing to retrieve it, is a prime candidate for skimo tactics. Technical grade isn’t a huge barrier, unless the terrain is very sustained, or a tight ski-clogging chimney impedes progress. The concept of doing big traverses is appealing, but it’s also a fun game to play to maximize your adventure/fun factor, by mixing and matching climbing routes with ski descents. After all, while climbing, the most tedious part of the day is usually the descent, and vice versa while skiing.

Why not make the most of it?

Launching into the first rockband of the Infinite Spur. Photo: Michael Gardner.

Nice turns on the upper mountain, descending the NE Ridge of Foraker after climbing the Infinite Spur. Photo: Sam Hennessey.

2021 was an amazing season. With our more refined tactics and gear, and a generous portion of good luck, we could take advantage of small available weather windows. In late April, we had a short time (two days) available at the end of a long thread of high pressure. We brought the skimo kit to the Isis Face on Denali, successfully climbed a new route, and then skied down the South Buttress. This adventure was more of a climbing objective: The route up was 2500m, with difficulties to WI5 M6, and the South Buttress was very icy and unskiable for long sections, although we were psyched to have the skis along, especially while straight-lining over crevasses and under seracs on the way down from Margaret Pass to the Kahiltna.

Following that jaunt, the weather deteriorated, but in a brief window (36 hours) where we didn’t feel comfortable going for a larger, committing ski objective, we were able to climb the classic Bibler-Klewin to the summit of Mount Hunter. This climb was followed by a short (I wish) interlude while we guided on Denali’s West Buttress, and then a whirlwind in town before finding ourselves, once again, at basecamp on the Southeast Fork of the Kahiltna.

We had summited the West Buttress during a stable weather period that had lasted almost a week, so we figured conditions were probably great for a technical objective. Unfortunately, our timing was off by about 24 hours, and it started to blow snow just as we arrived at the base of Denali. We decided to beat a tactical retreat to basecamp and develop a new plan.

Wide stems get you through the crux of a new route on the Isis Face. Photo: Michael Gardner.

Five days of crummy weather ensued, which honestly was a much-needed break. It was unpleasant: wet snow, warm temperatures, and an unfrozen glacier. Recreating was more akin to water skiing, so we mostly sat around, eating junk food and plotting our next move. It felt a bit like 2018, but this time we had the proper equipment, and had done the homework to make our dream a reality.

First, we knew we wanted to focus on Denali. Our time at work had left us with great acclimatization, and we didn’t want to waste it. Second, because of the warm temperatures and near-constant precipitation, we had a pretty good idea that there had been excessive snow accumulation, probably even at high elevations where cold temps often limit snow accumulation—often on Denali when it’s cold it snows the most between 10,000-12,000 feet—so technical climbing would be tedious and the skiing probably quite good.

Spirits are high on the Hanging Glacier—Cassin Ridge. Photo: Michael Gardner.

Of all the objectives on our list, a complete traverse of the mountain sounded the most appealing. We dialed down the climbing, opting for the moderate Cassin Ridge, but dialed up the skiing a bit, aiming for the first ski descent of the Northwest Buttress. As a bonus, we were also able to add Adam Fabrikant to the team. Adam has done many ski descents in the range in excellent style, and we knew his experience and trailbreaking strength would be invaluable.

The climbing on the Cassin was mellow (short sections of steep ice and rock climbing up to 5.8), but totally classic, and we arrived on the summit full of excitement for the ski down. We had timed our ascent to coincide with sun on the northwest aspect, and as we clipped in, the mountain lit up in the evening light. Soon we could see out to the tundra, and during the 10,000-foot run we found everything from windboard, to ice, to isothermic mank, but the prevailing conditions were boot-top to waist-deep powder.

Approaching the Cassin early in the morning. Photo: Michael Gardner.

Keeping it loose on the way down. Photo: Adam Fabrikant.

Of course, when you have 60mm underfoot, you sink to waist-deep a lot easier. Exiting the Peters Glacier, we could ski almost 10 miles on the dry glacier in just a little over an hour, taking a big chunk out of our final slog. It was indescribably beautiful moving from the high alpine to the tundra, and, when we finally were forced to switch to shoes, we walked to the road in a dreamlike state, just in time to catch the last bus of the day. Thankfully, the Park Service operates a shuttle from Kantishna to the highway, and it’s free for those leaving the Park. The full traverse took 64 hours, most of that spent awake. We crammed in with our skis alongside the lodge employees and tourists, none of whom seemed to quite understand where we had come from. Staring back at Denali, impossibly distant from the hot, mosquito-infested forest, we had trouble believing it ourselves.

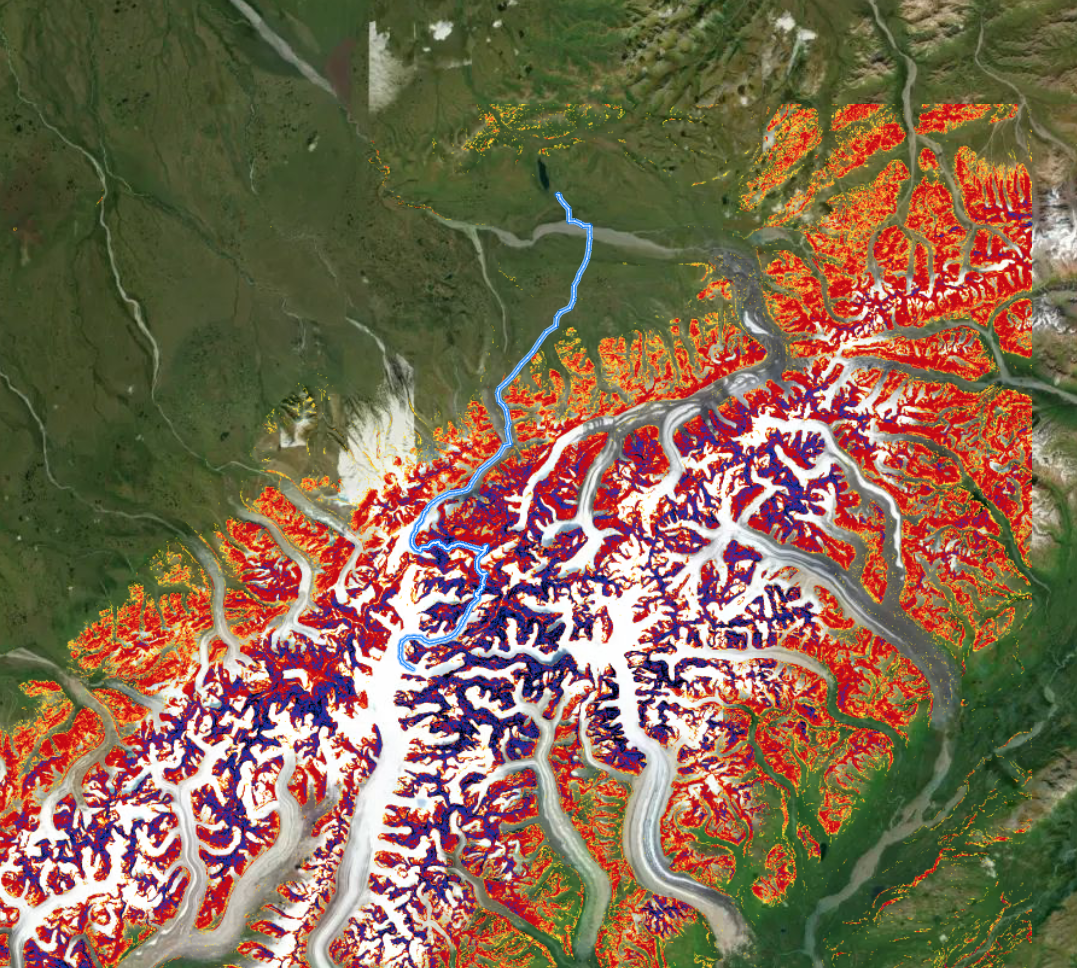

The Gardner, Fabrikant, Hennessey Denali Traverse: Ascend Cassin Ridge, descend the NW Buttress, exit via the Peters Glacier, stick thumb out at the road. GaiaGPS screenshot.

A swift creek crossing en route to the road. Photo: Sam Hennessey.

Sam Hennessey grew up in Port Angeles, WA, and had his first misadventures on skis in the Olympic Mountains. He moved to Bozeman, MT after college, where he currently works as a mountain guide and has a very nice storage unit.

Sam Hennessey grew up in Port Angeles, WA, and had his first misadventures on skis in the Olympic Mountains. He moved to Bozeman, MT after college, where he currently works as a mountain guide and has a very nice storage unit