The timing was oddly appropriate on Wednesday, preparing to fly out on Thursday for my final summer ski trip: my mother informed me that I should instead drive to visit my father in the hospital, where a relatively uneventful emergency room visit had suddenly changed for the worse. He had taught both me and my younger brother to ski, so the timing, or perhaps the juxtaposition, somehow made sense.

That my father, Melvin Charles Shefftz, had ever started skiing though in the 1950s always seemed wildly improbable. I once read of mainstream skiing as characterized by three successive stages: from adventure to sport to recreation (and since then onto real estate development perhaps). Back in the 1950s, skiing still had the aura of a rich man’s domain, and that of _crazy_ rich men at that.

My father was neither rich nor crazy. He was the son of immigrants too busy escaping the Russian Civil War to be concerned with escaping the city to slide down the side of snow-covered mountains. Furthermore, he had been afflicted with asthma as a young child, when treatment largely consisted of indoor confinement, as he longed to join the joyous cries of the neighborhood children playing outside in the snow. But a graduate school friend bullied him into trying skiing, and after a sleepless night so terrified at the prospect, he was hooked (even after later breaking his ankle that first season).

Then again, despite being a relatively mild-manner university professor, his father’s father’s side of the family had somewhat of a wild streak. Their immigration began when my paternal grandfather’s uncle as a young man — a la Jack and the Beanstalk — was supposed to sell the family cow at a local market, which he did, but instead of returning home with the proceeds, he bought a boat ticket to America. He became a sort of itinerant cattle herder, buying up single cows from small farms near Boston (until he died after being gored by a ram).

My father’s decades of skiing pretty much coincided with the nadir of backcountry skiing in the Eastern U.S. So his closest encounter with truly wild snow was probably when in the Alps he unwittingly wandered so far from the marked piste that he faced a long trudge back along the valley. I also never knew quite how to explain to him after describing some mountain I had just ascended and skied, that no, the mountain really wouldn’t be any better with chairlifts.

But I suspect he would have loved backcountry skiing, as he loved exploring, and was seemingly impervious to the elements. I remember once coaching an NCAA alpine ski team on the protected lower slopes of New Hampshire’s Cannon Mountain, when my father appeared at the top of our training course, coated with rime. He had taken the tram to the summit, and then been the only rider of the exposed upper-mountain quad during a blizzard. A ski instructor at our local area once told me how during an impressive blizzard he saw only a single rider on the chairlift braving the elements. My father. Still reading his newspaper of course.

As a professional historian, he was always reading, whether on the chairlift or otherwise. Once we were flying out west for a ski trip, and although the flight was long, perhaps six hours, I asked why he had reading material more appropriate for six days, or perhaps even six weeks. He explained, “What if terrorists hijack the plane and all I have to read is their boring propaganda material?”

He continued skiing until a few weeks short of his 75th birthday, when his lack of knee cartilage and worsening myasthenia gravis finally snapped his streak of nearly five decades of consecutive ski seasons. He was saddened by the abstinence from his favorite sport, but the last year and a half of his life was filled with joyous visits with his granddaughter Micayla. Her most recent history lesson from Grandpa was at my request, regarding the 1895 Venezuela boundary dispute. Micayla appeared sympathetic that he could not remember the exact spelling of the “Schomburgk” line. We should all have such mental faculties at age 82, or at any age for that matter.

One of my most cherished characteristics of my father is brought up by an old Calvin and Hobbes comic strip, which I clipped and then saved all these years, from before I was even married. I can’t find the image on-line anywhere, and posting my scanned copy is probably in violation of copyright laws, but you can find an essay about the strip that concludes with these words:“This Sunday strip of Calvin and Hobbes is a definite testament to Watterson’s skill at expressing his ideas and telling a story visually, as well as proof that a picture, often times, is worth well more than a thousand words.”

The irony is that the essay about the Hobbes strip comprises 1913 words. I’ll summarize it. Unlike a typical Calvin and Hobbes comic, this one lacks any acerbic conflict among the characters, in words or otherwise. Calvin looks outside excitedly at the snow, and then tries to interest his father in joining him for some outdoor fun. But the father is up against an impressively high stack of work papers, and Calvin slinks away dejectedly. The father tries to concentrate on his work, but, but, but . . . suddenly we see the father run outside to be greeted by Calvin with open arms and unrestrained joy!

Maybe if my father hadn’t spent so much time outside in the snow with his two sons he would have published that book he had always planned to write, and maybe he would have acquired some impressive reputation beyond the university students he personally taught over the span of five decades. Yet by giving us his time he earned the love of his family, and taught us the values that matter most, and set an example as a father that I hope to live up to for my daughter.

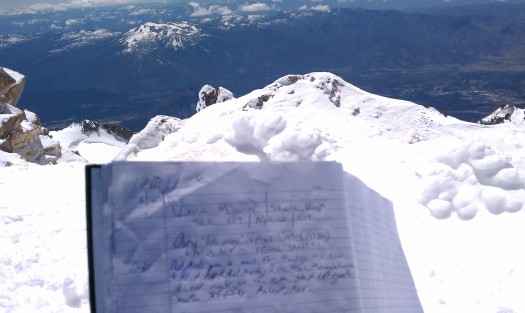

Shasta summit registry entry on June 30, 2011, with no idea that he would be with us for only 18 more days: 'Dad, thank you so much for teaching me how to ski. I hope that someday I can teach Micayla how to ski, and maybe we can even stand here together.'

My only regret is that I wish my dad had been given more time at the end: to see his grandson-to-be from my younger brother and his wife, and also to hear his granddaughter expand her vocabulary to say how much she loved him. But I’ll do it for her: I love you Dad.

WildSnow guest blogger Jonathan Shefftz lives with his wife and daughter in Western Massachusetts, where he is a member of the Northfield Mountain and Thunderbolt (Mt. Greylock) ski patrols. Formerly an NCAA alpine race coach, he has broken free from his prior dependence on mechanized ascension to become far more enamored of self-propelled forms of skiing. He is an AIARE-qualified instructor, NSP avalanche safety instructor, and contributor to the American Avalanche Association’s The Avalanche Review. When he is not searching out elusive freshies in Southern New England, he works as a financial economics consultant.