We love the bliss of October into early November turns. Despite gouged bases and maybe sparks (rocks lurk), early-season snow is often irresistible. But, early snow brings some precautions — in some mountain ranges— as the snowpack evolves. This conversation with Chris Dickson gives insight into why a love-hate relationship exists with the early snowfall.

This was the year I christened a new pair of rock skis. It’s inevitable: a meager snowpack, it’s early November after all, and the otherwise smooth un-dinged bases were bound to get scarred. With some p-tex, a set of vice grips, and epoxy, beautifying a ski base after nailing some rocks can be basic work. (Emphasis on the can be.)

Yet the reality of all this early snow has a downside when the weather systems eventually roll in cold and dry. Those conditions potentially set up a cycle where weak layers in the snowpack can sit buried below once the snow begins falling again. If you are new to the backcountry scene or want another perspective on loving and hating this glorious start to the season, hearing what Dickson says is beneficial. One piece of Dickson’s vibe is his disarming and welcoming nature — he can discuss technical aspects of snow science and make them understandable to the rest of us. He’s a true educator. We connected with Dickson last week. Dickson lives in Colorado’s San Juans, a place where backcountry users are all too familiar with facets and basal weak layers.

Dickson is also the host of the San Juan Snowcast, a podcast dedicated to discussing the snowpack in the range. You can read more about this hyperlocal podcast here. He is also a guide and educator with Telluride’s Mountain Trip.

As always, educating yourself about the snowpack and avalanche education, in general, is never a bad idea.

Chris Dickson: I think you’re getting into the love-hate relationship we have with early season snowfall. If you do know what early season snowfall means, which is the potential for a basal weak layer to develop at the ground of our snowpack, then it’s easy to be jaded by October snow storms.

But we love to see snow in general, especially in a place like the San Juan’s. We tend to have feast or famine winters, and in such a scarce snow ecosystem, any snow is good snow, and we’ll take what we can get! But at the same time, if it falls in October, and then it sits under a month of dry weather and high pressure systems, which we commonly get here in the San Juan’s through November, then this snow at the ground will become weak, and it’ll be the whole foundation for the season’s snowpack.

It’s like starting your snowpack on top of a house of cards. And then of course, everything that comes after that — it builds upon that weak foundation.

It’s a tough one for me and others who live here because we really enjoy seeing the early snow. And if it keeps snowing, then we have the opportunity to maybe have a really solid start to our season. And that’s kind of what I see in the next couple of storms, hopefully. But here’s the kicker, if the tap turns off in December, then the snowpack is going to facet–out. But, early season snow at least means we could have a base to ski on before Christmas.

WildSnow: So, let’s take a small step back and revisit some of the terminologies you are using. Old-timers and students of the snow scene might know these terms, but those new to snow science might not. So let’s drill down a moment on the facets and basal layers — can you describe what you’re talking about for someone who might be new to this?

Dickson: So I think it all starts with this fact: as soon as a snowflake falls out of the sky and lands on the ground, it begins to change. And it can change in two main ways. It can “round”, meaning the snowflake begins to break down, developing rounder edges which allows all the snowflakes to sit nicely with each other within the snowpack

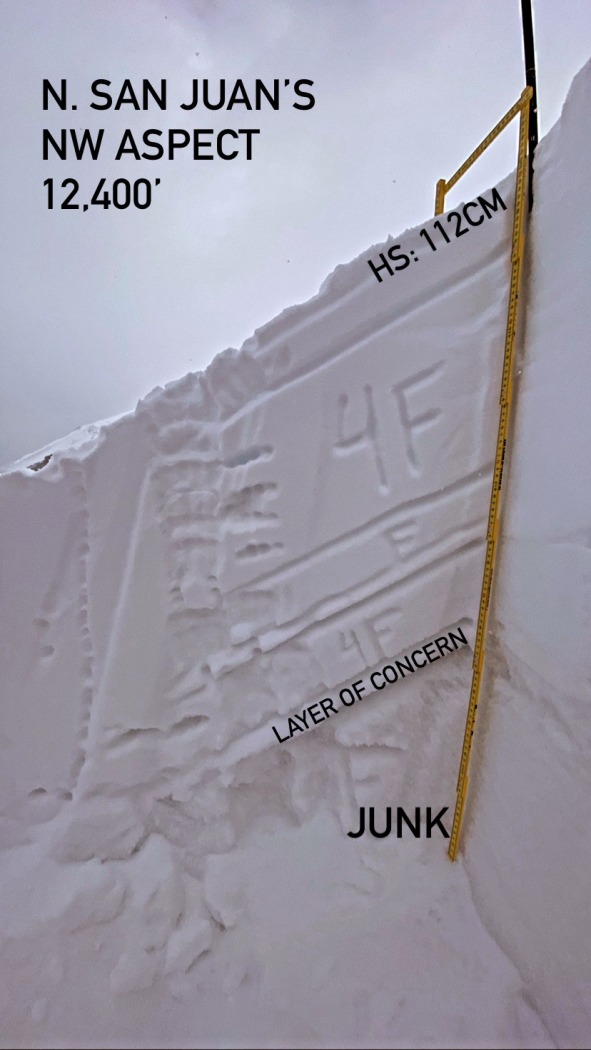

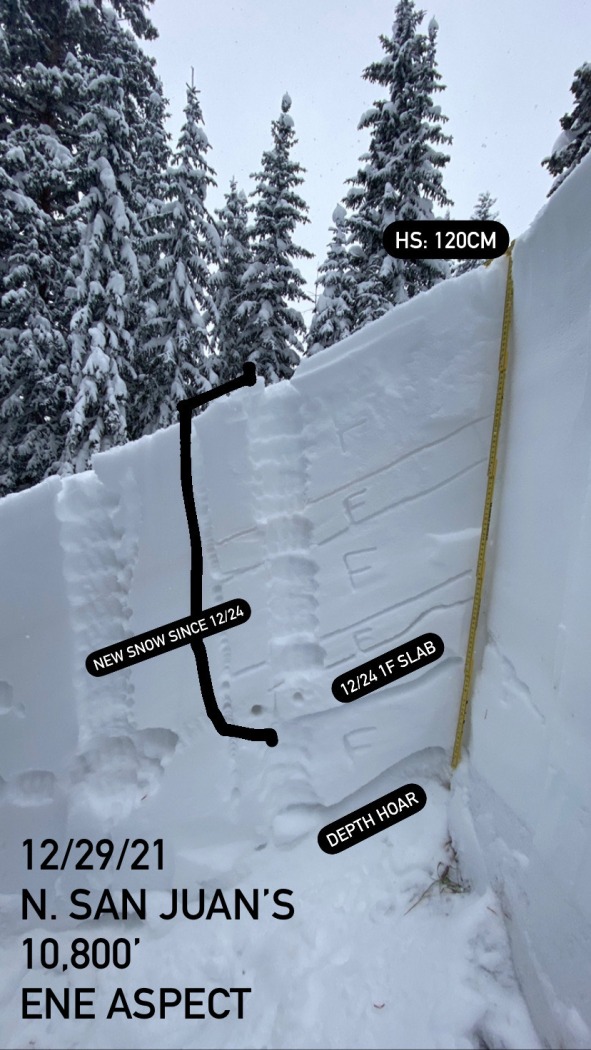

Or it can go the other direction, which is “faceting”. This process transforms the snowflakes into icey sharp-edged crystals which do not sit well with each other in the snowpack. After a lot of faceting, snow crystals can become “depth hoar” which are those large dried-out icey structures that kind of look like tiny Bugles in the snowpack.

The problem with this faceting process is that between these jagged angular facets, there is a lot of air space within the snow. Imagine filling a jar with marbles vs square blocks. The marbles represent rounded snow crystals, while the blocks resemble facets. Square blocks aren’t going to fit together nicely and there is going to be a lot of empty air space between each block. This is what happens when facets develop within the snowpack: it effectively creates a layer with a lot of air in it between weak snow crystals, and this creates potential for a collapse to occur within this layer. And that collapse can be the initiation of an avalanche.

So, why do we care? Well, if that snow sits on the ground through a long period of no snow and dry weather, it’s going to take that faceting route as opposed to rounding, especially here in Colorado, where it’s really cold and dry. We have a lot of clear nights that promote that faceting process, and that route of snow morphology, unfortunately for us, is what commonly happens here. So, we end up having all this snow that we refer to as “facets” once it’s taken that grain shape and form.

Furthermore, we call it a persistent weak grain because once it’s a facet, it likes to stay a facet and this type of snow grain can persist within the snowpack for a long time; sometimes, it just becomes a bigger and bigger facet and develops into “depth hoar”, that Bugle-shaped super facet. Essentially, the larger and more developed the facets, the weaker that layer of snow has become.

How facets form: Video from avalanche.org.

WildSnow: OK, so what might this problem look like as we eventually move into winter?

Dickson: Well, the irony is that if it doesn’t keep snowing, facets on the ground are not necessarily a problem; sometimes they soften the surface of the snowpack and they make it actually pretty fun for skiing. When you’re skiing on facets, we call that “loud pow” or “recycled pow.”

But the problem is, when that weak layer gets buried by a big storm and a big slab of cohesive snow gets put on top of those facets, then those facets become a buried persistent weak layer and we have the potential for persistent slab avalanches.

For folks who are out there traveling in the backcountry, there are some easy observations you can make to determine whether there is a weak layer underneath you. And I saw this today on my tour, when I ventured out into a big open north facing meadow, I got some shooting cracks to go through the snow. That meant there was some weak snow underneath this new snow, and as I stepped out onto it, the weak layer collapsed and translated cracks up through the new snow, which was starting to show some cohesion and slabby characteristics.

For the new tourer, that’s the telltale thing to look for: do you hear any collapsing (like whumphs) or do you see any cracking in the new snow? That’s a sign that there’s weak snow under the snow you are standing on, and it’s collapsing under your weight.

WildSnow: Can you summarize what the progression of the snowpack, so far, has been in the San Juans and how it might relate to what we have been speaking about?

Dickson: Sure thing, and it is a pretty common trend that happens almost every Fall for us here.

The first three days of October, it snowed a little bit every night, so probably a few inches per night, which added up to maybe a foot in the alpine — that was October 1st, 2nd, and 3rd. Then we had 20 days of blue skies and sunshine. They were nice sunny days, warm enough to be in a T-shirt, and then we had cold clear starry nights.

During that time, pretty much all the snow from those initial storms melted. Most of the snow on south, east, and west faces melted out, but snow on the steep north faces persisted through that period.

The next storm we got was October 24, and we got about eight inches that blanketed everything. That was followed by three days of melt where the snow on those sunny south faces pretty much disappeared, but the east and west aspects held on to their snow.

On October 27th, we had our next storm, the fourth of our season, and our snowpack was officially here to stay. For us, the most important thing to do in the early season is to figure out where that old snow persisted from early October, because that snow is the stuff that’s going to create weakness at the bottom of the snowpack.

For instance, where I was touring today, on an east facing slope, some of it had a southeast tilt, and some had a northeast tilt. As soon as we got to the northeast tilt, you could tell there was a lot more snow here, and there was snow from the earlier storms that didn’t melt out during those high pressure periods. And that’s where I started to see those collapses and some cracking. As skiers, we usually want to go to those shady cold north facing pockets, especially down here in San Juans, because that’s where the sun doesn’t shine, and that’s where the soft snow is, ie. good skiing. And unfortunately for us, that’s also where those persistent weak snow grains love to grow and exist.

WildSnow: Yeah, there are some lessons to learn about wishful thinking and hoping for an early winter.

Dickson: Indeed. The old timers and folks in the know are always like, “we don’t want snow right now!” It’s kind of this funny, nuanced understanding that, if you’ve seen it for a long time, you understand it, but it’s counterintuitive to the new backcountry skier who thinks that any snow is good snow.

WildSnow: Ok, let’s think about the scenario where you don’t necessarily have to think about this persistent weak layer deep into the winter. You know, sometimes we hear a persistent weak layer has “healed.”

Dickson: There are a few different scenarios or trajectories the snowpack can take that can erase this problem, especially at the ground level (aka the basal weak layer).

But the reality is, once we have enough snow protecting the weak snow at the ground, then the snow at the surface, during these long droughts we get midwinter in January, becomes faceted again, and that resets the problem to the surface. When that faceted snow surface gets buried, now we have a mid-pack persistence slab. And the problem perpetuates like this all winter.

We are constantly tracking the date these layers were buried — for example, the October 27 weak layer. I think it’s one of the things that never really goes away, because we’re always tracking a weak layer all winter long.

But, the trajectory where we don’t have to worry about it as much is if it keeps snowing a lot! If we build our snowpack deeper, and we insulate those facets from the environmental factors like cold and clear nights that cause more faceting, then that will actually slow down the faceting process and eventually even start to reverse it if the snowpack is deep enough. That’s a simplistic way to look at it, but shallow snowpacks are more likely to facet, whereas deeper snowpacks trend towards rounding.

Unfortunately, for us, we don’t have those steady incremental loading events like you have in the Pacific Northwest. We’ll have these big storms, and then it’ll sit for a few weeks, facet on the surface, and then we have the problem reset itself.

So it is one of the things we often have to deal with every year, at least for the first half of the season. We’re always worried about what’s on the ground, because as skiers, we can influence basically a meter down into the snowpack. Oftentimes, down here in SW Colorado, we don’t have more than a meter of snow on the ground until well into our winter. So we know that the weak snow on the ground is always there, lurking, and potentially under our influence.

WildSnow: That a solid breakdown about why sometimes the early snow can pose some risky situations in the future when considering avalanche danger. Anything else you want to add?

Dickson: I will say that all of the nuanced snow science stuff can be really intimidating for folks and it’s a bit of black box. To anyone who’s new to the backcountry and doesn’t want to get into dealing with all the uncertainty that goes into trying to understand things like persistent weak layers; there’s always non-avalanche terrain where you can find good turns. Playing on slopes that are less than 30-degrees, meadow skipping, is an awesome way to have fun in winter. And then there’s Springtime! I love what Doug always says on Totally Deep, that waiting until Springtime can be the safest and easiest way to play in the backcountry. There are avalanche hazards for sure in the Spring, but you’re not dealing with sketchy, really touchy, uncertain problems; it’s much more foreseeable and you can interpret and assess the avalanche problems much more easily in the Spring. Nothing wrong with waiting until corn season!

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.