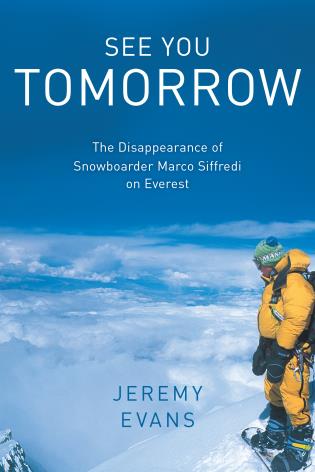

See You Tomorrow: The Disappearance of Snowboarder Marco Siffredi on Everest, by Jeremy Evans offers readers a glimpse into the motivations and story of the wunderkind snowboarder.

Back in 2001, Marco Siffredi pushed the edge of the possible as he made the first complete snowboard descent of Mt. Everest. In 2002, he returned to board the Hornbein Couloir, by any measure, a more audacious goal. Author Jeremy Evans deftly draws the reader in as he documents Siffredi’s life and examines his disappearance on the mountain.

On many levels, Jeremy Evans’ book See You Tomorrow: The Disappearance of Snowboarder Marco Siffredi on Everest, is both hard to pick up and put down.

Make no mistake; this is a great read. Evans populates the pages with anecdotes that humanize Siffredi, a wunderkind snowboarder born and raised in Chamonix. There’s no spoiler here; as the title announces, Siffredi went missing in September 2002 while attempting a snowboard descent from the top of the world via the renowned Hornbein Couloir.

At the time of his death at 23, Siffredi ranked among the most accomplished extreme skiers/snowboarders. He notched several spicy first descents within the gaze of his family’s home under the Aiguille du Midi and, in 2001, made the first complete Everest snowboard descent —summit to advanced base camp— down the mountain’s Norton Couloir.

In achieving that goal in 2001, Siffredi seemingly had nothing to prove in the niche world of extreme snow sliding. According to Evans, Siffredi, although presented as an introvert, still sought greater recognition. And he chased, a year after his 2001 feat, what many consider the jewel of extreme descents, a first descent of the storied Hornbein Couloir.

As stated, the pages are easy to turn. But by exhuming Siffredi’s story, and in some ways his demons, I continually tried, maybe wrongfully, to contextualize Siffredi in our social media driven world, where sometimes reality and perception are on the extreme opposite sides of the fulcrum. With a handy Instagram account and the right PR agency, I can imagine Siffredi would have earned the accolades he deserved. I’ll admit, until digging into the book, I had never heard of Siffredi. Would he have chased the elusive Hornbein descent a little more than a year after his Norton Couloir feat had he become widely respected and recognized? Maybe, maybe not. But certainly, I think it’s safe to assume he would have had more financial and team support in chasing the dream. Either way, his efforts on the mountain speak contrary to the ubiquitous siege tactics on 8000m peaks.

Siffredi was very much a purist. As explained by Evans, his mountain ethos speaks to those desiring a near out-of-body experience in the alpine while leaving a minimal impact. We are reminded that he often rode a descent’s crux because style matters, rather than set up a short rappel to mitigate the difficulties. And that brings us to the 2002 mystery that Evans sets up.

No one knows what fate befell Siffredi; his body was never recovered. But Evans posits several scenarios to discern the likely possibilities. So in a small way, the book reads like a mystery to be solved.

See You Tomorrow Book Trailer from Finisterre Visuals on Vimeo.

I was less interested in the mystery. However, I am keenly interested in what drives young people in the alpine and how they live a full life, their best life, despite family and friends stressing each time they depart for an adventure. The simple answer, I suppose, is to set them up for success by providing mentors and training to be safe and then hope they don’t fly too close to the sun. Undoubtedly, Siffredi lived with purpose.

Yet Evans periodically frames Siffredi’s immediate family by zooming in. And like any mountain tragedy, there’s always deep loss back home. That’s hard to retreat from in this book, which is not bad. It simply made See You Tomorrow hard to pick back up at times. If you’re not a parent or your close friends aren’t dreaming up first descents, this might not be your reaction. You can learn more about it in the book, but losing Marco to the mountains was not his family’s first experience with loss and skiing.

Reading Tom Hornbein’s, Everest The West Ridge, along with Evans’ book fully illuminates Siffredi’s audacious goal.

Good reads weave multiple threads together to make us care. Evans does that. Yet if you are new to Everest, and 8000m peaks in general, have a resource at hand, as it can help envision Siffredi’s audacity. The Hornbein Couloir becomes a geographic anchor along the book’s narrative arc. In 1963, Thomas Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld became the first climbers to ascend the couloir as they summited Everest, linking what became the West Ridge route. Hornbein wrote Everest The West Ridge, which I consider a classic, as it depicts an extraordinary effort and vision that still holds up to today’s modern standards. No spoilers here, but read it if you can before See You Tomorrow.

Being familiar with the Hornbein through past reading, what Siffredi planned in his solo snowboard descent is like trying to fathom the steely nerves, faith, and moxy of those who sat atop the early Apollo rockets as the engines booted and ignited; a tremulous prelude to many possibilities. There’s no imagining a film crew, drones, or the played “3-2-1 (state your name) dropping,” as Siffredi cut his initial arc across Everest’s North Face in 2002 — he was very much alone in his thoughts and actions. The book presents the beauty of a young man finding his path in a harried world, but it also makes it real that no matter how alone a solitary figure may be high on a mountain, they tow others along.

You can find the book at all the usual booksellers or order through your local independent book shop.

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.