With the Continental Divide rising in the background, Brian Parker makes risk assessments in the Wind Rivers.

Backcountry skiers “value being responsible risk takers whose decisions are grounded in competence–a status that requires training and experience.”

The seasonal pivot away from skiing came a month ago. Like many, though, I’m planning ahead. Part of this planning is meta; I’m thinking about how I think about risk in the backcountry. And to make this process more enjoyable, I’ve listened to the third season of Climbing Gold, a climbing-specific podcast. The latest season, thematically, explores several facets of risk. If you’re looking for a hot weather diversion, give it a listen.

Another less dial-it-back-and-be-entertained exercise is reading up on research exploring how our cohort of winter backcountry travelers perceives risk and recklessness.

The Journal of Risk Research, there is such a thing, published a paper titled “Expert and lay judgments of danger and recklessness in adventure sports” recently. The paper’s authors seem to get at helping answer why we participate in sports that we feel are inherently risky. Without getting too mired in the data, and not seeing the forest for the trees, there were some interesting nuggets.

Backcountry Vignettes

The first aspect of the study gathered responses from individuals not involved with adventure sports. As part of their research methodology, the authors created several scenarios for lay persons to explore how they judge danger and recklessness.

Here’s one scenario:

Steve is a ski tourer. He is a very competent and focused athlete and he has carefully developed his fitness and skills to engage in the sport responsibly. He has a lot of experience as a skier and mountaineer. He plans to ski a famous mountain – which lasts on average about 8 hours. Steve is told by the local authorities that over the last few years there have been some fatalities on this ski descent at a rate of roughly 1 in 160,000 skiers (~6 in 1 Million). Steve is 35 years old and has a partner but no dependents.

The researchers modified six parts of the scenario to establish different contexts. These contexts were; type of sport, gender of the participant doing the sport (in the above example, Steve is a male), are their dependents, was the activity done for charity, was the person trained and competent, was a guide used, and fatality risk of the chosen activity.

To illustrate the concept, here’s a second scenario:

Ryan is a runner. He is a very competent and focused athlete and he has carefully developed his fitness and skills over many years to engage in the sport responsibly. He has a lot of experience as a runner. He plans to compete in a long distance road running race around Scotland – which lasts on average about 8 hours. Ryan is informed by the course organisers that over the last few years there have been some fatalities during this race at a rate of roughly 1 in 160,000 runners (~6 in a million). Ryan is 35 years old and has a partner but no dependents.

The context difference here is running v backcountry skiing, with the other variables unchanged. The results suggest, maybe to no one’s surprise, that despite “background risks” held constant ( ~6 in a million die), running is perceived as much less dangerous and reckless than ski touring by a lay person. Without even peeling back the layers, the thought experiment is telling.

The second part of the study collected data from backcountry skiers using a vignette where the chosen sport was solely ski-touring. They then compared responses from experienced backcountry skiers and non-skiers to variations within the ski-touring vignette.

For those interested, here are the specific ski-touring contexts presented to experienced backcountry skiers and non-skiers : “All four vignettes use ski-touring with a male participant. We use (a) a vignette with all descriptors fixed at their baseline conditions (no dependants, not for charity, no guide, high competence, low fatality rate); (b) a vignette in which the fatality rate is 1:1600; (c) a vignette in which the activity is done for charity, and (d) a vignette in which the person doing the activity has low competence and is without a guide. In vignettes b-d all other descriptors are fixed at their baseline conditions.”

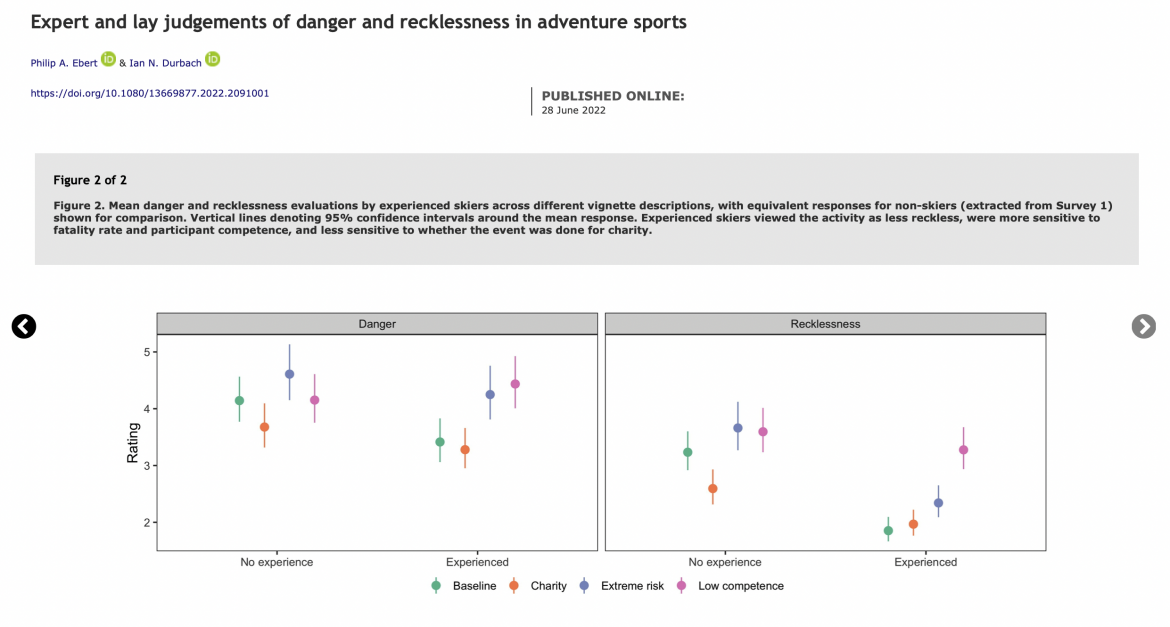

Expert and lay judgements of danger and recklessness in adventure sports: evaluations by experienced skiers across different vignette descriptions, with equivalent responses for non-skiers. Image: Philip A. Ebert & Ian N. Durbach

Ski-Touring Vignettes Results

According to the results, we ski tourers might, after all, be a rational lot. Here are the four highlighted results from the ski-touring specific vignettes.

— Experienced skiers gave lower overall recklessness ratings than non-skiers.

— Experienced skiers were more sensitive than non-skiers to variations in the fatality rate of the activity and the competence level of the participant.

— Experienced skiers were less sensitive to whether the event was done for external benefit such as a charity.

— Experienced skiers’ recklessness judgments were more sensitive to changes in activity descriptions than danger judgements.

There’s more. And I’m biased because I consider myself an experienced skier on most days, and I like to think I surround myself with rational people, and we serve a rational readership. Here we go.

— For baseline conditions, meaning no dependants, not for charity, no guide, high competence, low fatality rate, “experienced skiers gave lower danger and significantly lower recklessness ratings than those without any skiing experience.”

— Experienced skiers rated the higher-fatality scenario more dangerous and reckless than the baseline scenario. Again, we skiers may be sound of mind. In the same scenario, “there was no evidence of significant differences for either danger or recklessness ratings provided by non-skiers.” Go figure.

— “Skiers’ judgments were unaffected by whether the activity was performed for charity or not.” That’s not the case for non-skiers. According to the paper, “the activity is less dangerous and reckless if done for charity, although this difference was only statistically significant for recklessness.”

— “Experienced skiers rated an activity substantially more dangerous and reckless if undertaken by someone with low competence. … In contrast, non-skiers’ danger and recklessness judgements were essentially unaffected by the competence of the participant.”

The paper’s discussion section goes into more detail, explaining, for example, why experienced skiers perceive things the way they do as compared to their non-skier cohort.

So, it seems we may not be adrenaline junkies after all. We are a group of keen observers, who most often become educated, trained, and grounded to perceive risk in the mountains just like a layperson perceives everyday risks, say in a big city, with eyes wide open but relying on know-how and awareness.

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.