A study published in Applied Geology titled “Tracking decision-making of backcountry users using GPS tracks and participant surveys” integrates several data collection methods to answer questions about where we travel in the backcountry and how we make decisions in avalanche terrain.

The research attempts to answer the following questions:

1) “How do backcountry users make decisions in backcountry terrain?”

2) “What type of backcountry terrain do they use, as quantified using simple terrain metrics and ATES? And does this change due to user experience and posted avalanche hazard?”

3) “Do they alter their backcountry terrain use based on group factors?”

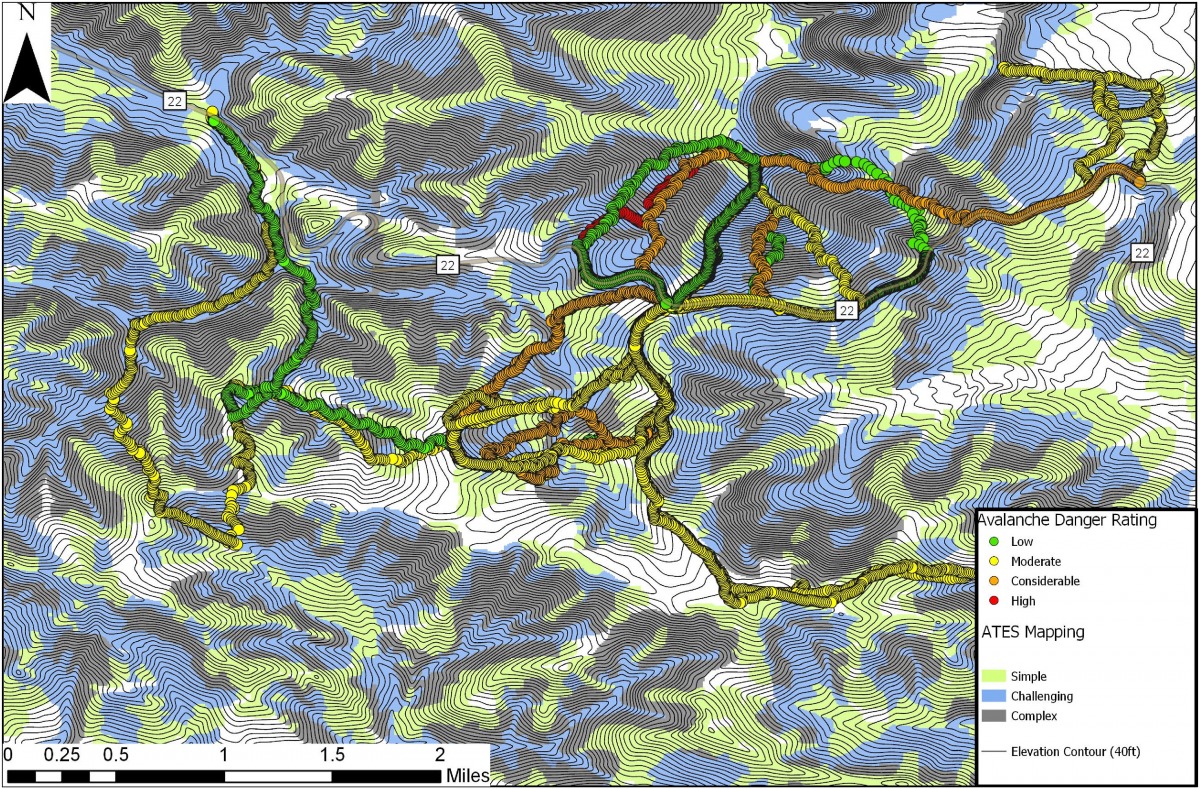

An example of GPS recorded backcountry ski tracks from Teton Pass, Wyoming, showing multiple tracks from different days, overlaid on our ATES mapping. The complex terrain is marked in black, challenging terrain in blue, and simple terrain in green. White represents non-ATES terrain. The tracks are color coded based on the regional avalanche advisory for the given day of travel. Image: J. Hendrikx et al.

In answering those questions, the authors, Jordy Hendrikx, Jerry Johnson, and Andrea Mannberg use, what they call, a “terrain focused paradigm.”

With varying terrain posing numerous potential hazards while touring, the authors posit “that geographic constraints may be the primary decision-making driver for such high-stakes decisions and act as the instigating factor for decision making. The presence of spatially distributed geographic and topographic features or conditions (snowpack, weather) instigates the need for a decision(s) throughout the duration of an excursion. Encountering potential hazard elements provides the impetus for social interaction among the group.” What this means in real life is that terrain features are often the points of discussion during a tour. This goes for changes in snowpack, encountering a steep

section, or some other feature.

The authors use the Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale (ATES) to categorize the terrain backcountry skiers/riders travel through. ATES uses three color-coded terrain type categories: simple (green), challenging (blue), and complex (gray). With GPS tracking data, among other details, the authors can determine the total duration of time a skier/rider/group spent in a specific ATES category.

***

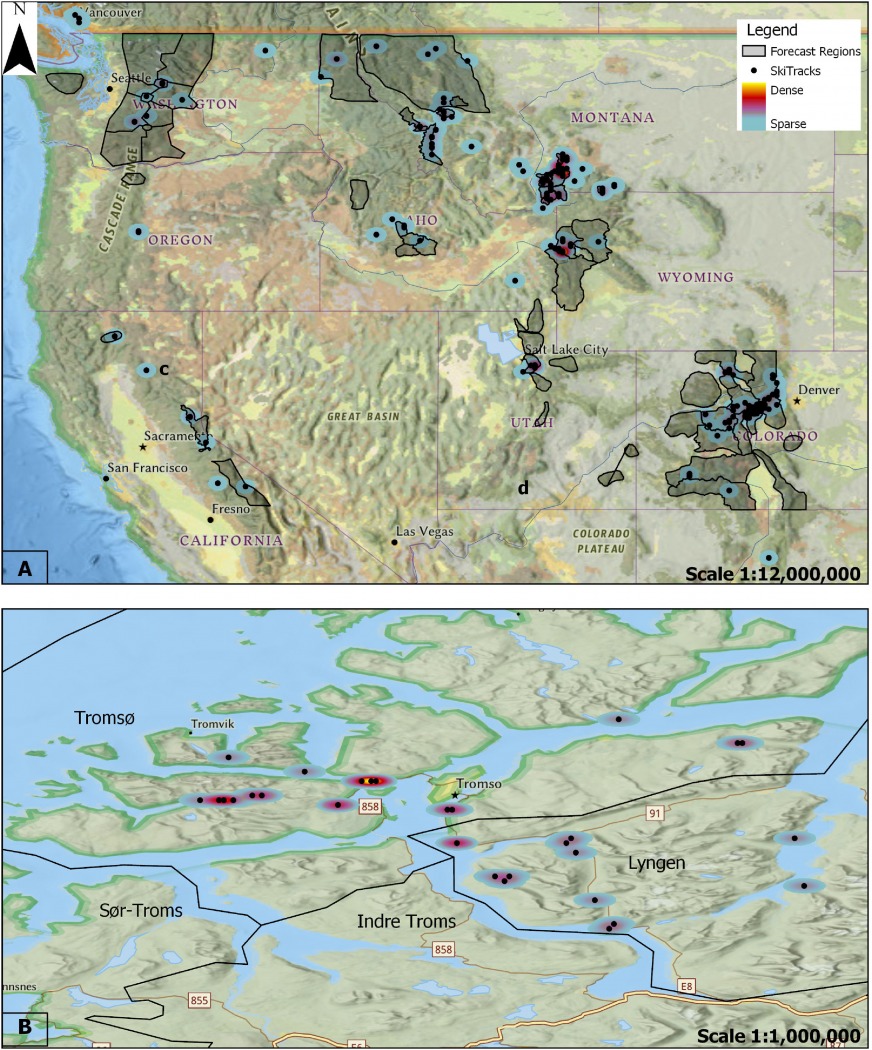

Survey participants self-identified as novice, intermediate, or expert and supported that designation with information regarding their ski experience and level of avalanche education completed. “Experts” score themselves “as significantly more skilled than self-assessed intermediate skiers,” according to the authors. Survey participants are also self-selected to participate in the study and most submitted just one or a few tracks. They have collected tracks from all over the alpine world but most are from N America and Norway.

The authors found the “typical” survey participant was:

– male

– aged 26-35

– has a college degree

– employed full-time (40+ hours/wk)

– takes part in other seasonal outdoor pursuits

Map showing the distribution of our track data, which were focused in the conterminous United States, and northern Norway. Heatmap symbology is in reference to the relative density of submitted GPS track data, where more tracks in one area represents higher density. Image: J. Hendrikx et al.

***

In the conclusion, the authors write, “specific to experience, we can clearly see that there is a statistically significant difference between self-identified intermediates and experts for a number of backcountry competencies.” Those competencies include perceived skiing skills, transceiver use during a search, and snow assessment. “In terms of decision making processes, there also seem to be differences for experts, in that they are more likely to try to determine real issues, use a well-defined process, and create a plan before communication.”

GPS tracking data is interesting, particularly when visually overlayed on a map including ATES zones/categories. The GPS track and the ancillary data embedded in GPS files, along with the survey responses, allow researchers to gain insights regarding skier/rider behavior and the terrain they choose to access.

When considering terrain use, “experts also had an increased exposure to avalanche terrain, when expressed as a percentage of their track, with higher percentages in all ATES classes,” state the authors. “In terms of total time spent in ATES terrain in general, and class 3 ATES terrain, experts also had a higher median time exposed.”

What exactly does that time “exposed” mean and how does it relate to ATES? The paper attempts to answer this by associating the day’s avalanche rating with each GPS track. The authors claim, “experts, while clearly traveling more in exposed terrain, and spending longer periods of time in avalanche terrain, may only be doing so under lower avalanche danger ratings.”

It is likely unfair to assume that experts are courting more risks by traveling in class 3 terrain when triggering a slide is likely. The authors write, “experts were in this [class 3] terrain more than intermediates, across all regional avalanche ratings, except high/extreme regional avalanche ratings.”

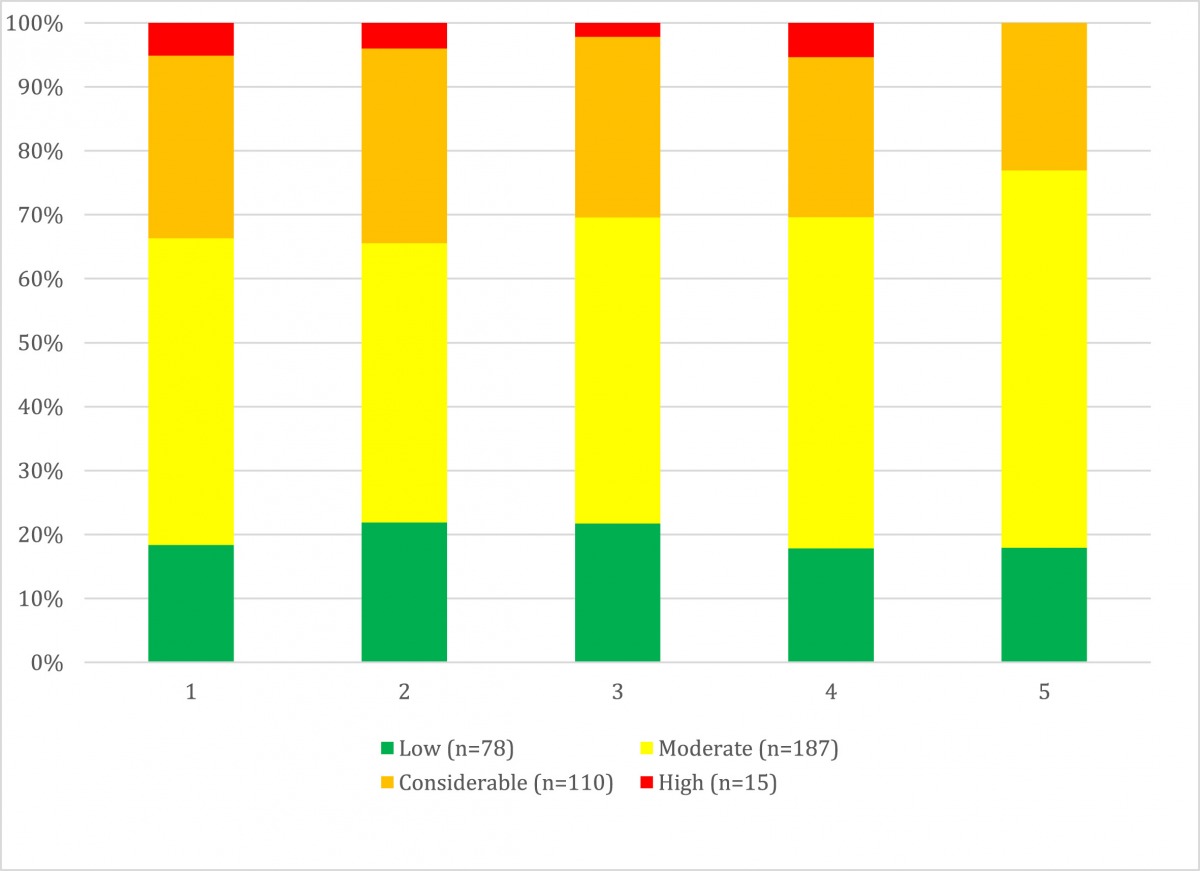

Group size was another element of the data revealing some interesting findings. The authors found no significant differences in group size when matching up with a specific avalanche danger rating. “There are similar proportions of group sizes from 1 to 4 under low, moderate and considerable avalanche danger ratings,” state the authors. (The avalanche ratings were denoted as low, moderate, considerable, and high.) The database also includes a very high percentage of solo skiers: Solo males constitute 24% of trips reported.

The researchers also explored whether group size corresponded to the percentage of a particular GPS track spent in “complex” terrain. Groups of five or more spent less time in complex terrain than other groups. Otherwise, the authors noted no significant differences.

Proportion of trips, as a function of group size, and coded by avalanche danger rating (n = 390 trips). Count of trips for each avalanche danger level is shown. Image: J. Hendrikx et al.

From a group composition perspective, here are the data reported:

Only male groups – 27%, n=115)

Only female groups- 1% (n=3)

Mixed gender groups of two – 12% (n=50)

Solo males- 24% (n=101) (considering respondents, this is the second largest type group)

The paper finds males in groups of two and three spent more time statistically than all other groups considered in complex avalanche terrain. They state, “Interestingly, solo males and mixed groups spent similar amounts of time in complex avalanche terrain, and solo females avoided all complex terrain (n = 3).”

The final group-related data mentioned also speaks to interpersonal familiarity— how well do you know your partners?

“Those who were most familiar with their partner(s) spent more time in complex terrain (median = 8.3%) than those that were not (median = 4.8%),” state the authors. “This makes intuitive sense because familiarity with a partner likely improves the communication needed to travel in more exposed terrain and trust in the event of an avalanche incident is likely higher among those who tour with the same people more frequently.”

The authors also looked at a skier/rider’s propensity to fall into a heuristic trap when decision making; think of heuristics as our “rules of thumb” that often come loaded with bias. According to this study, experience level does not make an individual or group more susceptible to heuristic traps. This finding, which the authors acknowledge, is at odds with some older and well-cited research by McCammon. (You can find those papers linked in this PDF. Also linked here is a paper, co-authored by many of the same researchers, that discusses in more detail how they would evolve the integration of the heuristics decision-making framework.

Some other macro-level takeaways are that most people choose not to ski high-risk terrain, and they are not skiing in extreme avalanche conditions. The GPS tracks cited show backcountry users accessing moderate slopes during relatively safe conditions. In an email exchange with one of the paper’s authors, Jerry Johnson, he explained “This is reassuring because it is exactly what avalanche courses teach that we should be doing–-the system is working.”

The data also suggest experts do, in fact, dial it back on high avalanche condition days.

One last key idea the authors raise is the limitation of GIS data (the information garnered from GPS and then rendered on a map); Johnson noted “our GIS data is not accurate to super fine-scale – none is. This means that we are missing fine-grain terrain features like wind pockets, small rollovers, etc. that tend to be the specific trigger points for slides. What we did here was a bigger picture analysis of terrain (although it seems in some accidents this may have been an important factor).”

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.