Sunrise in GTNP: a place to be prepared for all possibilities. Photo: Aidan Whitelaw.

We’ve all got opinions about what is best for layering in the backcountry. Settling on what works best for you often includes a bit of experimentation, hits and misses, and some knowledge of how your body thermoregulates. One need only scroll through the high-value comments from WildSnow’s layering archives to understand that not all human thermoregulatory systems are alike. Some of us run cold; some run hot; some split it right up the middle.

Before we dive into the topic at hand, apparel layering with an eye towards backcountry emergencies, here’s a solid layering resource from WildSnow.

Gary Smith’s comprehensive piece details what works for him from “skin to shell.” Smith guides us from socks, base layers, mid-layers, shells, and suggestions for hands and head. Manassah Franklin also adds some thoughts, allowing for another person’s perspective.

With emergencies in mind, layering may have a different look than simply the layers you set off wearing (presumably while skinning). A key mantra, either way, is to layer with wicking underlayers that can dump heat on the uptrack. When the moisture we produce cannot evaporate or permeate a mid-layer and possibly shell, sweaty skin has a chilling effect.

A ridge ascent in the Oregon Cascades packing many of the emergency essentials. Photo: Joe Madden.

A quick guide to daily driver tops:

I run cold unless I’m putting in a reasonable effort. Up top, I begin with a synthetic or synthetic/wool blend T-shirt; I go long-sleeved on colder, windier days. I layer next with a lightweight fleece hoodie. I vacillate between a Patagonia R1 hoody and The North Face Summit FUTUREFLEECE L2 hoodie—both in full zip. The TNF L2 seems a tad more air permeable, so I pick that if it’s recently washed. If it’s snowing lightly or there’s predicted precip, I bring a Norrøna Lyngen jacket made from Gore-Tex Active. I wear a Patagonia Pluma jacket constructed with Gore-Tex Pro, a more moisture-resistant fabric than Active when it’s actively dumping snow. If zero precipitation is forecast, I stash a Black Diamond Distance wind shell in the pack. It’s similar to the Patagonia Houdini with a slightly different fit. For extra insulation, I always pack a Patagonia Das Light Hoody. The Das Light is synthetic and features a dual zipper. There are several options like this out there.

A quick guide to daily driver bottoms:

I wear a TNF Summit FUTURELIGHT full-side zip pant if it’s colder or spitting snow. If warmish outside, I opt for an Arc’teryx Procline (the new version after eight years using the old softshell iteration). I’m a bit more flexible with pants, and I break my temperature rules often. But this is a solid rule for me: If it’s 25° F or below and windy, I wear 2/3 length cut-off lycra tights as a bottom base layer for added warmth. (Note: Lycra is pretty useless when wet.)

Layering for Emergencies:

So far, in terms of layering for safety, the basic system I’ve laid out allows me to dump heat or warm-up while skinning or skiing, moisture to wick, and remain somewhat dry in a snowstorm. For potential emergencies or emergency prevention, I pack additional items if I might be benighted (broken equipment, faulty navigation, or rerouting due to poor conditions), lying still as a patient, or attending to a partner requiring emergency care.

Indigo skies, but deep into puffy country.

Emergency Tops:

I’ll first revisit the puffy. When chilled on the ups or downs, I wear it. Ninety percent of the time, I use synthetic puffies. No chance of snow or rain; I might use a down puffy. That’s just my preference. The puffy is my first line of defense in an emergency: both for the victim and non-injured partner. I always bring a puffy on backcountry tours no matter the tour plan or weather conditions. The puffies I’m thinking of are on the lighter side—not full-on Alaska grade down jackets. This is an item I’m incentivized to take, meaning it is packable and lightweight. If you insist on down or live in the Rockies, we are reviewing an ether-light option: the Crazy Idea Levity jacket, a 950 fill-down jacket aimed to please gram counters (no measured weight yet, but…unobtainium light). The Levity seems like a winner for an emergency piece, or a warm but minimal down puffy with Italien styled sweetness built-in.

If it’s predicted to be cold, which for me might even mean my arbitrary 25° F threshold, I bring along an extra synthetic vest to supplement the hoodie in case of an emergency. For the past year, I’ve used Patagonia’s Micro-Puff vest. This medium vest sits nicely under my medium puffy. If I’m out on a day when it’s downright cold, in the 15° F range for me, or my group is going deeper, I consider bringing a second minimalist down puffy, not the vest.

Zahan Billimoria, noted big mountain guide and Samsara Experience founder, recently posted a great “how to pack for backcountry skiing” video. In it, he reminds us to stash a light, but spare, baselayer top in your pack. Removing a wet baselayer from an injured skier/rider can go a long way in their rewarming efforts.

Emergency Bottoms:

Backpack designer and man about Wilson, Wyoming, Gavin Hess, often packs a 3/4 length TNF product called the L3 Ventrix insulated knicker/overpant (no longer sold.) He says the overpant is “an underrated layer,” he stashes in his pack or wears on cold inverted mornings.

The weight cost-benefit to bringing this layer could go either way. But on those cold-blowing days, having insulated pants/knickers to layer over your ski pants can be miraculous when things don’t go as planned. Something to note, and it’s a fact often told: down loses its insulating properties when wet. Many down-filled overpant options are available. Norrøna’s Lyngen down knickers are one example. Think wisely – maybe go with synthetic insulated pants, as someone in an emergency may lay in or near the snow. Side zips are essential too, to fit over ski boots without taking boots off, or there are crampons involved.

Several companies make climbing-specific insulated belay pants. BD makes the Stance (530g), Rab makes the Photon (536g). They check the boxes for me: full zip, synthetic. They are, however, bulky to pack. On bigger missions or full-on expeditions, this is not a deal-breaker. But yes, semi-bulky.

(Head to eBay, I see a few TNF Ventrix knickers for sale.)

Patagonia’s new Das Light pant is coming online next fall (we’ll have a sample in our hands to test this week). Light (approx: 310g), synthetic, full-zip, packable. These insulated pants look like something I’d bring on any mid-winter tour and longer, more remote, spring tours/traverses, too. This item could be a trendsetter in the insulated pant category.

Emergency Hands:

Do I have Raynaud’s? I’m not sure. But I’ve diagnosed myself with it countless times: My hands quickly get cold. Maybe your hand circulation is not as suspect as mine. Having a pair of reliable, weatherproof mittens in the pack certainly can make a downed backcountry skier more comfortable, and in rare circumstances, could save digits.

Outdoor Research’s Alti Gore-Tex Mitts: a burly, waterproof, emergency mitten.

I’ve added burly mittens to the always-bring-along category. Over the years, I’ve experimented with numerous brands, none of them duds. But, a lesson I’ve learned, spending the extra cash on something durable, warm, and waterproof keeps the screaming-barfies at bay (usually). Overkill? Maybe. I’ve been loving the Outdoor Research Alti Gore-Tex Mitts. These are modular mittens, meaning they have an inner mitten that can be worn as a stand-alone mitt. These too will be reviewed soon, but I’ll note here, after being submerged in water for five minutes, there was no seam leakage, the mittens remained 100% dry. But…400g for the pair.

Camp’s Hotmitt’n, what Hess calls a sleeping bag for your hands.

Other options are out there for mittens, and they don’t necessarily need to be engineered for 8000-meter peaks like the ORs. Hess says he stashes “sleeping bags for your hands,” Camp’s HotMit’n (150g/pair) for emergencies.

Some prefer heavy gloves as a backup. That’s understandable, as they allow for more dexterity.

Emergency Head:

I do love my hats and buffs. Another always-bring-along is an extra mid to heavyweight hat I can place under a helmet–that means sans pom-pom. A dry hat is a warm hat. Imagine a worst-case scenario; having the ability to top off the clothing system with a warm, dry hat is key. Bring an extra. Even while going lighter in the spring, I stow an extra hat.

Bring a buff. They’re light and help keep your head warm when it’s windy or cold. Buffs can double as a snot rag too.

Extra Socks:

Extra socks don’t always make the pack list cut. But, if you’ve got room in the pack on your day outing, and it’s brrrr cold, maybe not a bad idea. On spring traverse, I pack an extra pair of socks to swap out if my feet are wet. They can easily serve as an emergency backup or for wet sock replacement for someone injured.

Apocalypse Equipment’s large and small Guide Tarps: The tortilla in the emergency layering system that bundles everything up. Photo: Apocalypse Equipment.

The Burrito Layer (sort of a clothing layer):

The last emergency layer is the wrap, like the tortilla, neatly capturing all the good stuff inside a burrito. In this instance, I’m thinking of a simple windproof and (maybe) weatherproof tarp. Options are out there. Shameless plug, the guy from Wilson makes a nifty guide tarp.

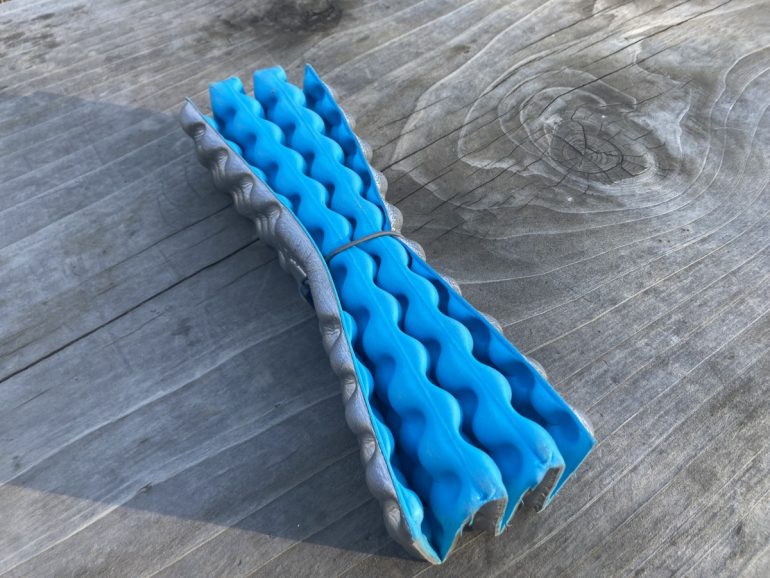

Alpinists have a long tradition of shiver-bivies. They know to use the removable foam back pad in their packs as ground insulation. Removable or not, skiers can do this too: sit on a backpack for insulation. I’ve also carried a small section of foldable Z-rest as emergency ground insulation.

A tidy section of a Z-rest can provide some ground insulation in an emergency.

Layed out here is no dogma, just suggestions to get us all thinking about the what-if scenarios. Let’s hear about what you carry in terms of clothing layers for those unexpected events we all hope we are prepared for.

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.