The raw amount of snow has been astounding. During a time when the West ricochets from heat domes and mega-drought, the metrics are boggling: more than 17 feet of snow (and counting) has fallen recently in California’s Sierra Nevada.

The Sierra Avalanche Center’s forecast for Dec. 30 through the morning of the 31st reads, “Strong winds continue to create drifted areas of snow. These wind slabs resulted in many avalanches yesterday throughout the forecast region. Use caution near or below slopes where blowing snow or cornices are present.”

If anything, the community embraces the sentiment that learning from others about the challenges of navigating safely in the backcountry is a cornerstone of building knowledge and sound practices. Many of us use apps to plan with savvy slope shading and downloadable files to GPS watches. We can log into avy forecasting sites pre-dawn and analyze wind data. Still, with all the new technology and analysis tools, fatalities continue.

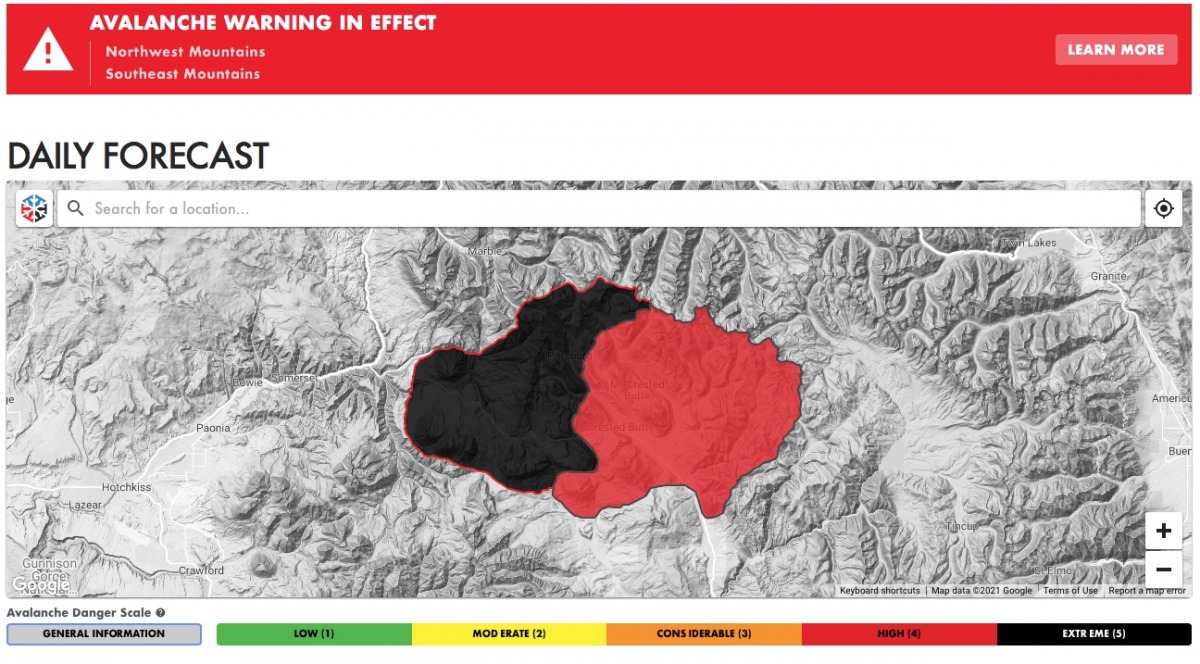

Which brings us to this, as one small geographic example, there’s simply a whole lot of red, and flashing black for “extreme,” on the Crested Butte Avalanche Center’s (CBAC) website.

A screenshot from the Crested Butte Avalanche Center’s homepage page forecasting for Dec. 31- Jan. 1.

The CBAC forecast for Dec. 31 – Jan. 1 for their Northwest Mountains reads:

An Avalanche Warning is in place for very dangerous conditions. Avoid avalanche terrain and runouts. The mountains around Crested Butte received snowfall for 9 consecutive days and some areas in the Northwest Mountains are nearing previous historical records for similar time frames. 12 to 20 inches of snow accumulated in the past 24 hours and another 15 to 20 inches is forecasted today. Avalanches breaking just in the storm snow from the past two days are very dangerous; avalanches breaking at the bottom of the week-long stormy period will be destructive and run full track reaching valley floors.

Backcountry winter sports have become more mainstream. With that, the grim statistics become headlines. As our thoughts are with the family and friends of loved ones lost, we hope to list and study these tragic accidents to learn and prevent further ones. While acknowledging that we are entering into an exceptionally unpredictable snowpack across the west, it is important to remember that avalanches are always unfriendly, unexpected and the results are frighteningly binary. There are days when we get away with it, never knowing how close we came to making similar mistakes, and days when we are not so lucky.

On Dec. 13 six skiers were caught in a slide in the Silver Basin area of Crystal Mountain – a ski resort in Washington. At the time, Silver Basin was closed and unmitigated. According to the Northwest Avalanche Center’s (NWAC) initial report, three skiers were fully buried, one of which died. Later, a sixty-six-year-old was identified as the victim.

The NWAC incident summary includes this statement:

“NWAC Forecast Zone: West South Zone

Avalanche Danger Rating (Above, Near or Below Tree-line):

The forecasted avalanche danger was Considerable near and above tree-line and Moderate below tree-line at the time of the accident.”

You can read a full forecast for that time and zone here.

“Standing in the crown.” A screenshot from the GNFAC investigation into the avalanche on Dec. 27 on Scotch Bonnet Mountain outside Cooke City, Montana.

Five more avalanche fatalities have been documented since the Silver Basin incident, which occurred about two weeks ago, as the snow began to fly in the Cascades, Sierras, and the Rockies.

Two 17-year-old juvenile males were killed in an avalanche with a location described by the Teton County Sheriff’s Office as “near Relay Ridge in the vicinity of Ryan Peak, west of Driggs,” in the Big Hole Mountains. The press release states both were buried; one was riding a snowmobile, the other skiing. The Bridger-Teton Avalanche Center does not forecast for the Big Holes.

On Dec. 24, a soft slab avalanche in the Diamond Peaks near Colorado’s Cameron Pass claimed another skier’s life. The Colorado Avalanche Information Center notes the slope angle was 38-degrees, with the avalanche occurring in sparse trees. The avalanche was specified as being two-three feet in depth, 15 feet in width, and running approximately 100 feet. The slope was facing east to northeast.

Initially, this was a party of four familiar with the zone. The CAIC report states, “They were aware of the avalanche danger and planned to avoid the large northeast face of Diamond Peaks.”

The incident involved only two skiers, as the other half of the group returned home. As a whole, the group had made several runs together. The surviving member of the avalanche, according to the CAIC report, stated, “the group experienced ’20 or more’ collapses of the snowpack during the morning.”

The CAIC’s Backcountry Avalanche Forecast summary for the day of the accident read:

Heavy snow and strong winds are creating very dangerous avalanche conditions. The most dangerous portion of the zone is in the north around Cameron Pass and Rocky Mountain National Park. This is where the most snow is falling. Avalanches can release naturally and run long distances. Pay attention to what is above you and avoid traveling under steep slopes, especially those that face a north through east direction. Even if you find an area with less snow and less dangerous conditions, winds are building thick slabs near ridgetop so avoid these areas too.

Additionally, an Avalanche warning was issued covering the day of the tragedy and read:

An Avalanche Warning is in effect for most of the mountains in Colorado. Heavy snow and strong winds are creating very dangerous avalanche conditions. Expect very large avalanches to run naturally and long distances on Friday. Travel in avalanche terrain is not recommended.

The reporting of these tragic events is a reminder to be aware – we’ll leave it at that. It is, however, worth any backcountry skier/rider’s time to review the important information the CAIC details in their professional incident reports. In particular, the “Comments” section is informative. If you missed it up top, here’s a link to the CAIC’s report.

Last season in Colorado, 12 people lost their lives in avalanches, including nine skiers and one snowboarder. One of those individuals was Gary Smith, longtime contributor and gear editor of WildSnow.

Most recently, in Cooke City, Montana, on Dec. 27, two snowmobilers were buried and killed in an avalanche. The snowmobilers were on Scotch Bonnet Mountain. According to the Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center, two in the party of eight were stuck on the SE-facing slope. Two other members rode up to assist with the digging out when the avalanche triggered “soon after.”

According to the full Scotch Bonnet Mountain incident report, “It broke 4-5 feet deep, ran 300 feet wide and 500 feet vertical and killed 2 riders, burying them under 4-5 feet of debris. Everyone had rescue equipment and they were recovered by their party.”

Avalanche forecasters do life-saving work collecting data and disseminating understandable and actionable information. In this case, Doug Chabot, the Director of the Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center, and Ian Hoyer, an Avalanche Specialist, put together a comprehensive report worth reviewing for its detailed snowpack and weather analysis.

On the day of the avalanche in Cooke City, the avalanche forecast read:

Consistent snowfall for the last five days brings our storm total to 31-37″ equal to… 3.5″ of snow water equivalent (SWE) in the mountains around West Yellowstone and Cooke City. The combination of recent snow and moderate winds from the southwest creates dangerous avalanche conditions. While the wind will ease off today, recently formed 1-4′ deep drifts will remain unstable. Avalanches failing on weaker layers of snow in the mid and lower snowpack are a possibility and would be large and dangerous…. steer clear of wind-loaded slopes and carefully assess the snowpack and terrain features in non-wind-loaded areas prior to entering any avalanche terrain.

With the significant caveat that visibility is limited, we have not seen or received reports of widespread avalanche activity during this storm. However, we have good indicators of instability such as large “whumphs” triggered by skiers near Bacon Rind on Friday (details) and unstable snowpack tests throughout the area failing and propagating within new snow layers and on weak layers near the ground.

The avalanche danger is rated CONSIDERABLE on wind-loaded slopes where human-triggered avalanches are likely and MODERATE on non-wind-loaded slopes where avalanches are possible.

We want people to be safe. And we want to minimize the cascade of grief associated with the loss of life. WildSnow has a vast archive of information related to avalanche safety and how to take precautions before you even set foot outdoors. This is a time when good information, and well-presented information regarding avalanches, is available for free on the Internet.

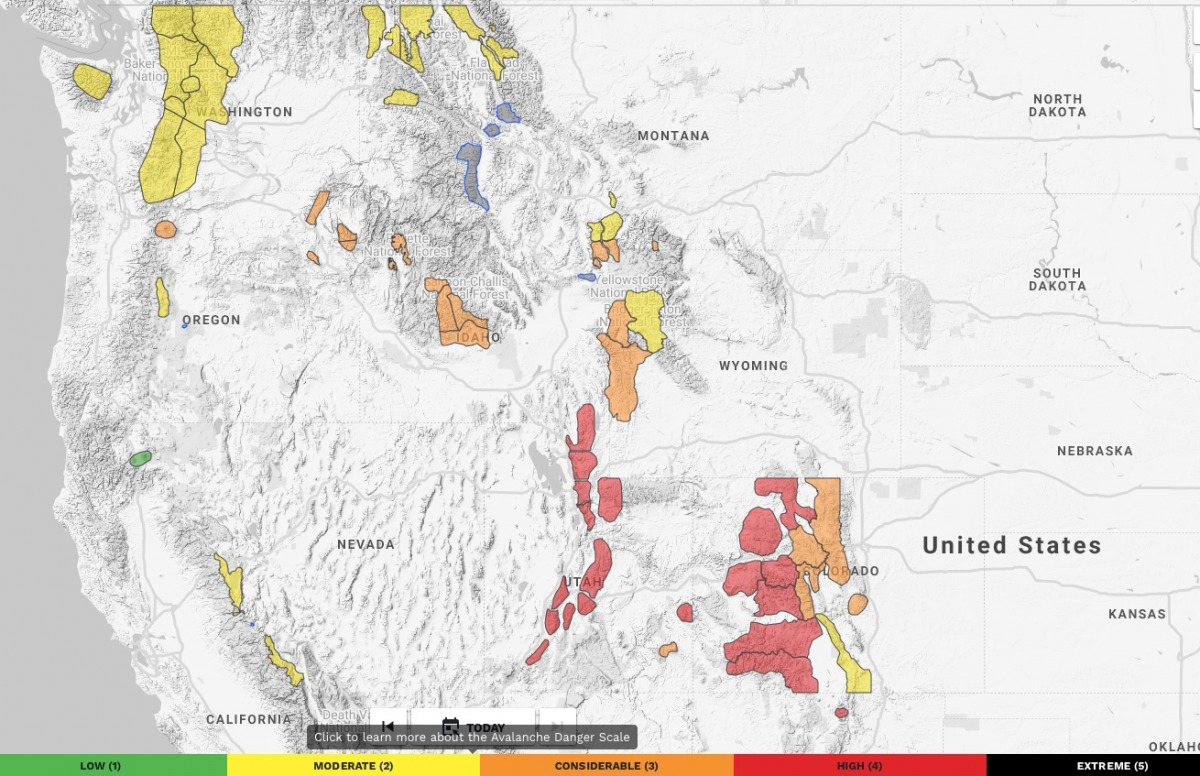

A Dec. 31 screenshot of the avalanche.org homepage. Utah. portions of Wyoming, and Colorado are flashing red.

We’re hoping the red blinking zones appearing now on a forecast map are an overt warning and an easier read than the trickier to travel yellow and orange zones.

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.